MARIANI’S

Virtual

Gourmet

April 19, 2020

NEWSLETTER

❖❖❖

IN THIS ISSUE

THIS WEEK

How the Give and Take from

Everyone Everywhere

Made American Gastronomy

the Most Diverse in the World

By John Mariani

NEW YORK CORNER

LOVE AND PIZZA

Chapter Four

By John Mariani

NOTES FROM THE WINE CELLAR

The Best Restaurants Are Selling and

Delivering Their Best Wines at Discount Prices

By John Mariani

❖❖❖

How the Give and Take

from Everyone Everywhere

Made American Gastronomy

the Most Diverse in the World

By John Mariani

It

is too facile simply to say that all people

are immigrants from somewhere, but in the case

of North America, everyone had

to get here from somewhere else, and everyone

brought with them their own

culture, all of it eventually suffused

throughout the American continent,

giving us all the richest cornucopia of foods of

any country in the world.

The first

immigrants came at least 15,000 years

ago. But it was not until Christopher Columbus’s

arrival in 1492 that the

Eastern and Western hemispheres collided

gastronomically in a titanic event to

be called the “Columbian Exchange.” The Genoese

explorer had specifically been

hunting for a spice route to the Orient—spices

then being worth their weight in

gold for Europeans who craved them—but instead

Columbus found a new world with

foods like potatoes, tomatoes, corn, cacao, sweet

and hot peppers, beans and

strawberries, all of them shipped back to Europe,

where people were astonished

by these wholly unknown foods.

The first

immigrants came at least 15,000 years

ago. But it was not until Christopher Columbus’s

arrival in 1492 that the

Eastern and Western hemispheres collided

gastronomically in a titanic event to

be called the “Columbian Exchange.” The Genoese

explorer had specifically been

hunting for a spice route to the Orient—spices

then being worth their weight in

gold for Europeans who craved them—but instead

Columbus found a new world with

foods like potatoes, tomatoes, corn, cacao, sweet

and hot peppers, beans and

strawberries, all of them shipped back to Europe,

where people were astonished

by these wholly unknown foods.

Imagine Italian food without

the tomato, Irish

food without the potato, Indian, Thai, and Chinese

food without the chile

pepper. And no chocolate anywhere but in Mexico.

Now consider that the

Columbian Exchange brought to America

wheat,

coffee beans, chickens, domesticated ducks,

cattle, bees, pheasants and

dozens of fruits and vegetables like artichokes,

carrots, yams, eggplant,

garlic, olives, lemons, apples, pears, rice and

tea. Imagine the American prairie

with millions of buffalo but no wheat fields

waving, Ohio and New York with no

apple orchards, the Hudson River once teeming with

sturgeon but the Hudson

Valley devoid of wineries, the Carolinas without

rice paddies. Such was the

radical transformation of gastronomy on both sides

of the world, and it caused

empires to grow and nations to go to war over

American plantations.

New York with no

apple orchards, the Hudson River once teeming with

sturgeon but the Hudson

Valley devoid of wineries, the Carolinas without

rice paddies. Such was the

radical transformation of gastronomy on both sides

of the world, and it caused

empires to grow and nations to go to war over

American plantations.

From every immigrant culture

came new foods and

new ways to cook it: pigs brought by the English

to the earliest colonies were

now roasted as barbecue; the Germans who settled

in the Midwest in the early

19th century grew hops to make beer, the Spanish

grapes to make wine. Africans

taken as slaves brought their yams and ground

nuts, which became important crops in

the South. French Huguenots who emigrated to

Louisiana from Acadia in 1755

adapted their native dishes to become chile-spiked

Cajun jambalaya (right)

and crawfish

boils.

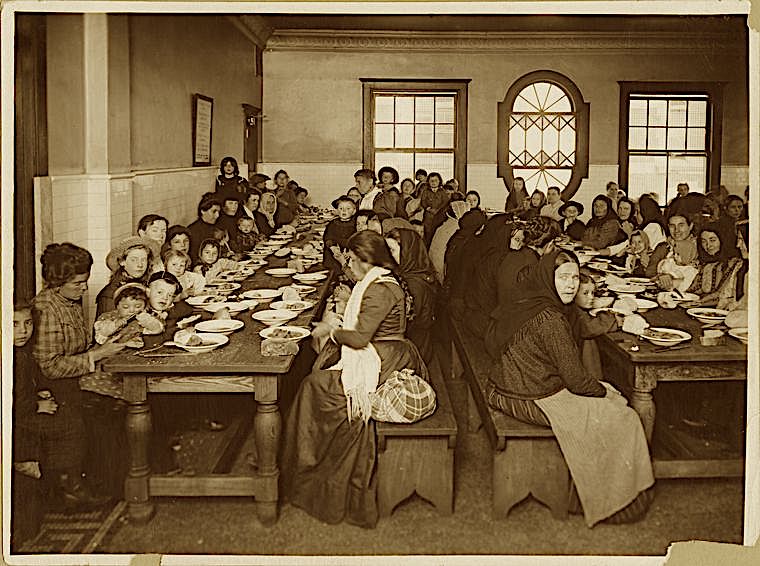

The

streets were not paved with gold but with

food markets, so the new arrivals often could

spend less money for much more

food in greater variety than in their home

countries. Also, their practical

need to adapt to their new world, coupled with a

deep nostalgia that caused

them to cling to the old, required using the

former to satisfy the latter.

Italian- or German- or Chinese-American, even

Tex-Mex cuisines, were all

filtered through memory but made by necessity with

what was available. Hunger

may have driven them to America, but the ability

of the immigrants to adapt

helped them prosper and feed their families in

ways unimaginable before.

The

streets were not paved with gold but with

food markets, so the new arrivals often could

spend less money for much more

food in greater variety than in their home

countries. Also, their practical

need to adapt to their new world, coupled with a

deep nostalgia that caused

them to cling to the old, required using the

former to satisfy the latter.

Italian- or German- or Chinese-American, even

Tex-Mex cuisines, were all

filtered through memory but made by necessity with

what was available. Hunger

may have driven them to America, but the ability

of the immigrants to adapt

helped them prosper and feed their families in

ways unimaginable before.

After the Civil War, poor

Southern Italians

brought the tomato back to

America to

produce a rich hybrid called Italian-American

food; the Jews of Eastern Europe

did the same, selling pastrami and knishes, latkes

and bagels in delicatessens,

while others ran the seltzer concessions and candy

stores. Chinese workers on

the western railroads of the 1860s adapted their

noodle dishes to become chow

mein, while the Irish made corned beef and cabbage

into  a

signifying dish,

though one totally unknown back in Ireland. The

Greeks created an entire diner

industry of which there was no trace back in

Greece. For so many immigrants, entering

into the United States’ welcoming food markets was

easy access to the American

Dream.

a

signifying dish,

though one totally unknown back in Ireland. The

Greeks created an entire diner

industry of which there was no trace back in

Greece. For so many immigrants, entering

into the United States’ welcoming food markets was

easy access to the American

Dream.

American food culture was

give-and-take, making

do, diversifying, modifying, and expanding, all

the while maintaining a revered

connection to the way it was done back in the old

country. There was no such

thing as “soul food” back in Africa, but here it

was full of rice and beans,

fried chicken and collards, pork chops and sweet

potato pie, developing the

name soul food in the 1960s as a part of ethnic

pride in African-American

culture. The

French never ate

potatoes or ever saw a French-fried potato until

the early 19th century, but

love of the spud was ubiquitous in America.

Italians could open an

Italian-American menu and not recognize dishes

with names like veal parmigiana,

chicken tetrazzini, fettuccine Alfredo, chicken

Vesuvius, hero sandwiches or

Italian cheesecake, much less ever go to a New

York-style Italian steakhouse

that served huge baked potatoes, shrimp cocktail

and five-pound Maine lobsters.

No resident of Tokyo or Osaka had  ever heard of negimaki

or California rolls.

And certainly no Mayan or Aztec had any concept of

what chili con carne,

chimichangas or fajitas could possibly be.

ever heard of negimaki

or California rolls.

And certainly no Mayan or Aztec had any concept of

what chili con carne,

chimichangas or fajitas could possibly be.

American

restaurants have a history of

adaption—curry houses, chop suey parlors,

pizzerias, rathskellers, Irish

bars, delicatessens, cafeterias and chili parlors

were all American adaptions

by immigrants who may never have eaten at a

restaurant back in the old country.

The pizza, which originated in Naples in the 17th

century, became far better

known and widely sold in America by 1950 than it

was in Italy until the 1980s,

and the Japanese imported the idea of Benihana of

Tokyo teppanyaki grills,

renaming them Benihana of New York (left).

The tiki bar (below), as

envisioned by “Trader Vic”

Bergeron in Oakland, offered a vast menu of dishes

completely made up to sound

like they came from Polynesia, like crab Rangoon,

bongo bongo soup, and the Mai

Tai cocktail. A Greek immigrant named Thomas

Andreas  Carvelas perfected soft

ice cream and called it Carvel. The remarkable

first Horn & Hardart

Automat, constructed using German machinery,

opened in Philadelphia in 1902.

Yogurt was popularized in the1940s by Barcelona

immigrant Daniel Carasso, who

created the Dannon brand, later adding fruit

preserves to create the first

“sundae-style yogurt.”

Carvelas perfected soft

ice cream and called it Carvel. The remarkable

first Horn & Hardart

Automat, constructed using German machinery,

opened in Philadelphia in 1902.

Yogurt was popularized in the1940s by Barcelona

immigrant Daniel Carasso, who

created the Dannon brand, later adding fruit

preserves to create the first

“sundae-style yogurt.”

Drive-ins, soda fountains,

fast-food chains,

pancake houses, fish camps, ice cream parlors and

barbecue joints lined the

American highways, many of them done up in the

shape of the food they served,

like White Castle in Wichita, Randy’s Donuts and

Tale o’ the Pup, both in Los

Angeles.

Then, in

1939, the exhibitors at the New York

World’s Fair (left)

showcased the kind of cuisine that was more like

what was actually

being eaten in France, Italy, Czechoslovakia,

Formosa, and other countries.

None was so influential as the Fair’s French

Pavilion restaurant, later

recreated as Le Pavillon in New York by French

immigrant Henri Soulé, who set

the standard and template for what became

French-American haute cuisine. Its

menu of frogs’ legs Provençale, consommé

royale, pâté en crôute, and

chocolate mousse were

slavishly copied by all French restaurants to

follow, with names like La

Grenouille, La Caravelle and Le Périgord.

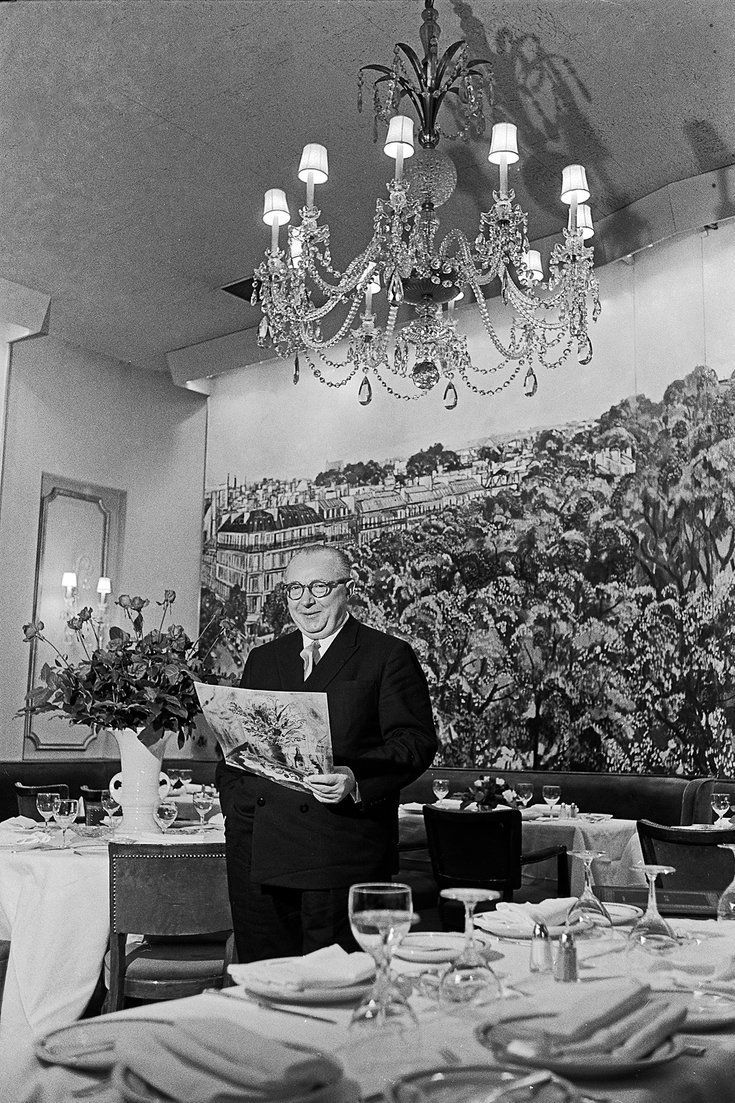

Still, after World War II, the

nation’s gastronomy

was in real danger of turning away from its

immigrant roots based on seasonal,

fresh  ingredients

and toward mere convenience and cost effectiveness

of frozen

and canned food, not to mention TV Dinners. As

Henri Soulé (right)

once moaned, “Some

of the richest people on Earth will dine here

tonight [at Le Pavillon]. And for

all the money on Earth, I couldn’t give them the

simple good things that every

middle-class Frenchman can afford from time to

time. Six Marennes oysters. A

partridge—very, very young. Some real primeurs—the

first

spring vegetables. A piece of Brie that is just

right. ... And some fraises des

Bois.”

ingredients

and toward mere convenience and cost effectiveness

of frozen

and canned food, not to mention TV Dinners. As

Henri Soulé (right)

once moaned, “Some

of the richest people on Earth will dine here

tonight [at Le Pavillon]. And for

all the money on Earth, I couldn’t give them the

simple good things that every

middle-class Frenchman can afford from time to

time. Six Marennes oysters. A

partridge—very, very young. Some real primeurs—the

first

spring vegetables. A piece of Brie that is just

right. ... And some fraises des

Bois.”

Yet by the 1970s, new waves of

immigrants,

especially from Asia, brought more and more new

foods, many of which were soon

planted in American farms. Overnight delivery by

FedEx and DHL from everywhere

made a cornucopia of wild mushrooms, fresh

seafood, cheeses and extra virgin

olive oil.

A little book that

became a bestseller, Diet for a

Small Planet by Frances Moore

Lappé (1971), and the pronouncements about the

healthfulness of the so-called

Mediterranean Diet that stressed eating

vegetables, grains and oils over

proteins and carbohydrates had an enormous effect

on the post-war baby boomers,

who were soon relishing the “ethnic” foods of

their own ancestors, leading to

more interest and hunger for “real” Italian food,

“real” Greek food, “real”

Spanish food, rather than the hybrid cuisines they

had grown used to since the

1950s.

A little book that

became a bestseller, Diet for a

Small Planet by Frances Moore

Lappé (1971), and the pronouncements about the

healthfulness of the so-called

Mediterranean Diet that stressed eating

vegetables, grains and oils over

proteins and carbohydrates had an enormous effect

on the post-war baby boomers,

who were soon relishing the “ethnic” foods of

their own ancestors, leading to

more interest and hunger for “real” Italian food,

“real” Greek food, “real”

Spanish food, rather than the hybrid cuisines they

had grown used to since the

1950s.

As

a result of more than 400 years of immigrant

history, America has not just the richest

gastronomy in the world—one that

ravenously accepts from other food cultures while

influencing them in

return—but one in which all those who accepted the

challenge to come here

contributed to and enjoyed. With all of them—from

the seafarers of Alaska and

the slaves of the South, the wheat-growing Swedes

of the Plains and the

Vietnamese boat people of Seattle, the

cannoli-makers and pastrami-briners, the

folders of phyllo and the smokers of trout, the

pretzel twisters and the tortilla

patters, every one of them has contributed to our

vast and delectable potluck

of so many wonderful things.

By John Mariani

LOVE AND PIZZA

Since, for the time being, I am unable to write about or review New York City restaurants, I have decided instead to print a serialized version of my (unpublished) novel Love and Pizza, which takes place in New York and Italy and involves a young, beautiful Bronx woman named Nicola Santini from an Italian family impassioned about food. As the story goes on, Nicola, who is a student at Columbia University, struggles to maintain her roots while seeing a future that could lead her far from them—a future that involves a career and a love affair that would change her life forever. So, while New York’s restaurants remain closed, I will run a chapter of the Love and Pizza each week until the crisis is over. Afterwards I shall be offering the entire book digitally. I hope you like the idea and even more that you will love Nicola, her family and her friends. I’d love to know what you think. Contact me at loveandpizza123@gmail.com

—John Mariani

Cover Art By Galina Dargery

At

Columbia Nicola had no such problem with the

male students, who

either seemed to come from privileged

backgrounds and cared very little about

their course work or were quite the opposite,

burying themselves in their work

and competing very intensely, sometimes openly

nasty to their fellow

students.

Nor was Nicola

particularly interested in jocks, especially

at Columbia, whose sports teams

had deplorable records.

At

Columbia Nicola had no such problem with the

male students, who

either seemed to come from privileged

backgrounds and cared very little about

their course work or were quite the opposite,

burying themselves in their work

and competing very intensely, sometimes openly

nasty to their fellow

students.

Nor was Nicola

particularly interested in jocks, especially

at Columbia, whose sports teams

had deplorable records.

Nicola did have a momentary crush on one

professor, a lecturer in Psychology who had

a Dutch name so difficult to pronounce that he

asked his students to “just call

me Diercks.”

But he turned out to be such a dullard in

class that she saw no point in pursuing

him. And then there was

her professor of the History of Modern Art,

whose own name, Rhys St. John, she

found strangely charming, because she never

heard of anyone outside of an

English drawing room comedy with such a name. At first she was

embarrassed by not knowing whether Rhys was

pronounced “Reese” or “Rice,” and it was

attached to a last name that in the

first day of class he pronounced as “Sin Gin,” a

sound so exotic to Nicola that

he might as well have been from Sumatra. But he

definitely was not. “Reese Sin Gin” was half

Welsh, half

Irish, a mongrel mix evident in the red-gold

cast of his carefully mussed long

hair, which he constantly brushed from his brow

and around his ears in the

presence of his female students.

At six-foot-one, he towered over most of

them, but since Nicola was

herself five-foot-nine, the playing field was

not quite so tilted in his favor

as with other women students.

St. John, who apparently owned just two,

very similar brown tweed

jackets, had a habit of lecturing with a

cigarette in his fingers that he never

actually smoked, carefully wafting the smoke in

the air like filigree and very

slightly tapping the ash into a small aluminum

foil tray on his desk. He’d bring the cigarette

close to his

lips, then pause to say something he believed

was brilliant as he let his eyes

focus on one of the women students.

Quite often that was Nicola.

At

the end of each lecture St. John would put out

the cigarette, which he’d probably

bummed from a male student, and finish what he

was saying in a low tone of

voice, “ ... and after that, van

Gogh”—pronounced like he was clearing his

throat of phlegm, “van GOCK”—“put

down

his ragged paint brush ... and shot himself

through his own sad

heart.” Then

St. John would very

gently close the book he had lying open

throughout the class, even though he’d

never read a word from it, and he’d sniff and

mutter, “hm.”

It did not take Nicola long

to

recognize that St. John’s hand movements,

curlicues of smoke, and modulated

speech were all part of a pattern, one that was

in many ways effective in

teaching his subject; he kept his students awake

most of the time and even

imparted some thoughtful ideas for their

consideration.

But she also knew that the act was

aimed squarely at the women in his classes and

St. John’s reputation for

philandering made for widespread gossip, much of

it true. One

time he came to class with a

chipped tooth, daring not to glance at a female

student whose ring finger was

bandaged that day.

The first

time Nicola met with St.

John in his office to go over what he expected

of her in the coming semester,

she had applied some lipstick before entering.

Getting up from his leather

swivel chair and rising to his full height, his

first words were, “Well, I must

say you women students get lovelier each year,”

delivered with a lilting,

burring brogue.

“Come in, come in,

sit down, Miss--?”

“Santini, Nicola Santini,”

she

said, smiling slightly.

“Well, you're as pretty as

your name,

Miss Santini. Sit down, sit down.

So let’s talk about the coming semester,

what I expect of you, and, of

course, what your own interests might be.”

Nicola momentarily wanted to

be

taken in by St. John’s charms but she was savvy

enough to know they were well

practiced, so she dove right in to discuss what

her interests were, ignoring

for the moment her professor’s.

“I’m most interested in

Italian

Renaissance art,” she began.

“Isn't everyone?” he

interrupted

with a light laugh.

Nicola plowed on: “So, while

I

want to know as much as possible about all the

visual arts, I think that’s

going to be my focus, especially the Venetian

painters.”

“Tintoretto, Titian,

Veronese.”

“Yes,” she said. “I

don’t think I have any particular

talent for painting myself, but I believe I

would make a good teacher.”

“At the college level?”

“Absolutely.”

“So you’re aiming to go to

grad

school in Art History?”

Nicola smiled and turned her

head.

“Yes, if I can afford it. It’s gotten very

expensive.”

St. John patted his tweed

jacket

pockets. “Hm, you don’t happen to have a

cigarette, do you?”

“Don’t smoke,” she answered.

“Well, no matter. Now,

about grad school, since I haven’t

had you in class for very long, I don’t know how

good a student you are, but I

have heard some of the other

professors speak highly of you.”

Nicola widened her eyes and

said,

“Really? They’ve spoken to you about me? I know

so few of them.”

“Well, let’s say I might have

asked about you.

I’ve seen you

around campus and here in the halls.”

At this Nicola relaxed her

shoulders, sensing that St. John’s interest was

increasingly non-academic in

nature. But

she told herself

simply to stay cool and not to encourage him in

any way.

“So what do you expect from me?”

she asked.

“Oh, not that much. This is a

pretty basic course, and I try to cover a lot of

material.

So if you do the readings and a decent

five-to-seven-page paper, you should do fine. I do like students who

show real interest, though. I

swear some of these people sit in

class with their eyes half closed throughout the

whole semester, never asking a

question, seemingly terrified I might ask them

one. They cut more classes than

they attend.” Then, putting his hand very

lightly on Nicola’s forearm, he said,

“May I confide in you?”

Nicola said nothing. He said,

“I

have certainly noticed that you do

not fall into that crowd. I think you’ve asked

some very good questions in

class and, if I’m not mistaken, you’ve never cut

a class.”

Nicola shook her head and

said,

“Not when my parents and I are paying for this.”

The word “parents” drew St.

John

up and he said, “Of course, of course.

I wish more students had that attitude.

Too many of them are just trust

fund babies whose parents pay for every dime of

their education, so they just

don’t really care. Most of them take my course

just to fulfill a curriculum

requirement.”

Now Nicola thought it best to

lay

it on the line: “I care very much. I don’t come

from a rich family and I don't

live in a rich community. I’m a Bronx girl and I’m proud of it, so I never take

what my parents have done for

me for granted.

I also don’t know

if, assuming I do go to grad school and

eventually teach, I will ever be able

to repay them in every way I’d like to.

I know what my grandparents did, coming

to this country with very little

and making sure their children and my brothers

and sisters got the best

education possible. Columbia is a

real stretch for a family like mine, and I never

forget that for a minute.”

Bronx girl and I’m proud of it, so I never take

what my parents have done for

me for granted.

I also don’t know

if, assuming I do go to grad school and

eventually teach, I will ever be able

to repay them in every way I’d like to.

I know what my grandparents did, coming

to this country with very little

and making sure their children and my brothers

and sisters got the best

education possible. Columbia is a

real stretch for a family like mine, and I never

forget that for a minute.”

“That is so

terrific,” said St. John, “Christ, if

I only had more students like you, my job would

be a lot easier and much more

rewarding.” Then he paused, looked Nicola up and

down, leaned over and put his

hand again on her arm, almost whispering, “So

... you’re not just smart and

beautiful but you’ve got a real moral

compass, too. Amazing. And very rare.”

"Thérèse sur un Banquette" (1932) by Balthus

Nicola kept

herself from saying

something stupid like “I bet you say that to all

the girls” because she knew he

had a practiced retort for something like that.

Instead, she said, “Well, thank

you. I hope I live up to your faith in me.”

St. John almost bowed. “And I

in

yours,” which he realized sounded like bad

grammar, even slightly creepy. He

stood up and said, “So, then, see

you in class Thursday.”

Nicola said yes, smiled and

left,

noticing that as she walked away St. John had

arched his head to watch

her. Nicola

muttered to herself,

“Christ, this man is

trouble,” and

wiped her lipstick off on the back of her hand,

as if she’d just been kissed by

a drunkard. She then went to the library to read

St. John’s next assignment, a

book on the painter Balthus.

❖❖❖

FINEST WINES FOR TAKE-OUT

By

John Mariani

The Wine Wall at Mastro's in the Post Oak Hotel in Houston, TX

One of the ironies of the

current pandemic is

that you may now be able to enjoy your favorite

meals from fine dining

restaurants as well as drink discounted

prestigious wines from their list.

In an industry with small profit

margins to

begin with, and a significant percentage of those

profits coming from wine and

spirits sales, restaurateurs are scrambling with new

business models to keep

them afloat during the coronavirus pandemic. And

those that have managed to

stay open by offering take-out and delivery service

have found that their

customers may have as good an appetite for fine

wines as they did on premises.

Sauvage

restaurant in Brooklyn has turned its

website into an on-line wine shop, with most bottles

costing $20-$30, and June

Wine Bar, also in Brooklyn, is selling selections at

50% off.

Such offers are really

rather drastic,

considering a restaurant may buy a bottle of wine

from a distributor for about

half the price you’d pay in a wine shop, then hike

up the price on the wine

list 100-300 percent.

Such offers are really

rather drastic,

considering a restaurant may buy a bottle of wine

from a distributor for about

half the price you’d pay in a wine shop, then hike

up the price on the wine

list 100-300 percent.

Even a few of the grand hotels of

Europe are

now offering take-out food and wine from their

classic menus for both in-house

guests and locals. The restaurants at the

176-year-old Baur

au Lac (left)

in Zurich,

Switzerland, are closed but you can order on-line

and have it delivered to your

home, including wines such as a Paladin Brut

Millisimata Brut Prosecco 2018 for

$17.60 and Saint-Saphorin Grand Cru “Les Blassinges”

from the Vaud region for

$19.65.

At

New York’s Michelin-starred Italian seafood

restaurant Marea, wines on their

reserve list are all 25% off, including prestigious

Italian labels like Alteni

de Brassica Sauvignon Blanc 2015 from Gaja, among

the most illustrious Italian

wine producers, which runs $350 on the regular list

but $262.50 for take-out.

At

the restaurants at the Post Oak Hotel in Houston, which

includes Mastro’s

Steakhouse, Keith Goldston, master sommelier of

parent company Landry’s Inc., is

even pairing Gaja wines with two pizza offerings: Ca'

Marcanda Promis 2016 with a pepperoni, marinara

and mozzarella pizza for $70, inclusive, and a 2014 Barbaresco

(right)

with a roasted mushroom,

white truffle oil and oregano pizza for $225.

“We’re also offering all 39

selections of Gaja wines at a 20-50% markdown from

the wine list price,”

Golston said.

Mastro’s

Steakhouse, Keith Goldston, master sommelier of

parent company Landry’s Inc., is

even pairing Gaja wines with two pizza offerings: Ca'

Marcanda Promis 2016 with a pepperoni, marinara

and mozzarella pizza for $70, inclusive, and a 2014 Barbaresco

(right)

with a roasted mushroom,

white truffle oil and oregano pizza for $225.

“We’re also offering all 39

selections of Gaja wines at a 20-50% markdown from

the wine list price,”

Golston said.

According to Gaia Gaja (left), fifth

generation of the family that owns the company, “In

these difficult

times fine dining and fine wines are surely a

luxury, but they can also be

a source of support for people confined at

home. A take-out of a fine meal

and wine is a way to bring home a taste of normalcy

and hope. I think it’s a

great service to people. We are seeing some

restaurants in Italy doing this

too,” citing San Lorenzo restaurant and Pierluigi

restaurant in Rome and Ribot

in Milan.

According to Gaia Gaja (left), fifth

generation of the family that owns the company, “In

these difficult

times fine dining and fine wines are surely a

luxury, but they can also be

a source of support for people confined at

home. A take-out of a fine meal

and wine is a way to bring home a taste of normalcy

and hope. I think it’s a

great service to people. We are seeing some

restaurants in Italy doing this

too,” citing San Lorenzo restaurant and Pierluigi

restaurant in Rome and Ribot

in Milan.

At

Wolfgang Puck’s Spago

(right) in

Beverly Hills,

which has always had a strong celebrity and show

business clientele, wine sales

have  been both at the value end

and the high end, now discounted. “We have an offering that

ranges from $18 to $650 and now

most wines we are selling are between $25 and

$100,” says Philip Dunn, Spago’s

Director of Wine and Spirits/Sommelier. “Our

prices for the most part are

better or at least the same as most off-premise

retailers. We have

surprisingly sold a fair amount of

Champagne, Ruinart Rosé, Dom Pérignon,

vintage Krug, Deutz and Laurent Perrier as well as

Moët & Chandon mini

bottles. Others that do well are Gaja in

half-bottle, Groth Reserve

Cabernet Sauvignon, Jordan Cabernet Sauvignon and

Pichler & Puck Grüner

Veltliner. Our offerings change as we

run low on stock.”

been both at the value end

and the high end, now discounted. “We have an offering that

ranges from $18 to $650 and now

most wines we are selling are between $25 and

$100,” says Philip Dunn, Spago’s

Director of Wine and Spirits/Sommelier. “Our

prices for the most part are

better or at least the same as most off-premise

retailers. We have

surprisingly sold a fair amount of

Champagne, Ruinart Rosé, Dom Pérignon,

vintage Krug, Deutz and Laurent Perrier as well as

Moët & Chandon mini

bottles. Others that do well are Gaja in

half-bottle, Groth Reserve

Cabernet Sauvignon, Jordan Cabernet Sauvignon and

Pichler & Puck Grüner

Veltliner. Our offerings change as we

run low on stock.”

At the restaurants within

the Post Oak Hotel, Goldston says, “We are seeing a

little bit of value

shopping, but most of our guests are ordering their

usual favorites and we are

even seeing a slight uptick in ‘trophy wine’ sales

as some are seeing this as

an opportunity to drink great wines—‘if not now,

then when?’” Puck's famous salmon and caviar pizza (above) is part

of their take-out program.

Asked

if wine sales through

take-out have been a good income producer at a time

the restaurants are closed,

Goldston said, “Absolutely, and they are especially

appreciated as they are a

revenue stream that doesn't require a lot of labor.”

Sponsored By

Any of John Mariani's books below may be ordered from amazon.com.

The Hound in Heaven

(21st Century Lion Books) is a novella, and

for anyone who loves dogs, Christmas, romance,

inspiration, even the supernatural, I hope you'll find

this to be a treasured favorite. The story

concerns how, after a New England teacher, his wife and

their two daughters adopt a stray puppy found in their

barn in northern Maine, their lives seem full of promise.

But when tragedy strikes, their wonderful dog Lazarus and

the spirit of Christmas are the only things that may bring

his master back from the edge of despair.

The Hound in Heaven

(21st Century Lion Books) is a novella, and

for anyone who loves dogs, Christmas, romance,

inspiration, even the supernatural, I hope you'll find

this to be a treasured favorite. The story

concerns how, after a New England teacher, his wife and

their two daughters adopt a stray puppy found in their

barn in northern Maine, their lives seem full of promise.

But when tragedy strikes, their wonderful dog Lazarus and

the spirit of Christmas are the only things that may bring

his master back from the edge of despair. WATCH THE VIDEO!

“What a huge surprise turn this story took! I was completely stunned! I truly enjoyed this book and its message.” – Actress Ali MacGraw

“He had me at Page One. The amount of heart, human insight, soul searching, and deft literary strength that John Mariani pours into this airtight novella is vertigo-inducing. Perhaps ‘wow’ would be the best comment.” – James Dalessandro, author of Bohemian Heart and 1906.

“John Mariani’s Hound in Heaven starts with a well-painted portrayal of an American family, along with the requisite dog. A surprise event flips the action of the novel and captures us for a voyage leading to a hopeful and heart-warming message. A page turning, one sitting read, it’s the perfect antidote for the winter and promotion of holiday celebration.” – Ann Pearlman, author of The Christmas Cookie Club and A Gift for my Sister.

“John Mariani’s concise, achingly beautiful novella pulls a literary rabbit out of a hat – a mash-up of the cosmic and the intimate, the tragic and the heart-warming – a Christmas tale for all ages, and all faiths. Read it to your children, read it to yourself… but read it. Early and often. Highly recommended.” – Jay Bonansinga, New York Times bestselling author of Pinkerton’s War, The Sinking of The Eastland, and The Walking Dead: The Road To Woodbury.

“Amazing things happen when you open your heart to an animal. The Hound in Heaven delivers a powerful story of healing that is forged in the spiritual relationship between a man and his best friend. The book brings a message of hope that can enrich our images of family, love, and loss.” – Dr. Barbara Royal, author of The Royal Treatment.

|

The Encyclopedia of American Food and Drink by John F. Mariani (Bloomsbury USA, $35) Modesty forbids me to praise my own new book, but let me proudly say that it is an extensive revision of the 4th edition that appeared more than a decade ago, before locavores, molecular cuisine, modernist cuisine, the Food Network and so much more, now included. Word origins have been completely updated, as have per capita consumption and production stats. Most important, for the first time since publication in the 1980s, the book includes more than 100 biographies of Americans who have changed the way we cook, eat and drink -- from Fannie Farmer and Julia Child to Robert Mondavi and Thomas Keller. "This book is amazing! It has entries for everything from `abalone' to `zwieback,' plus more than 500 recipes for classic American dishes and drinks."--Devra First, The Boston Globe. "Much needed in any kitchen library."--Bon Appetit. |

"Eating Italian will never be the same after reading John Mariani's entertaining and savory gastronomical history of the cuisine of Italy and how it won over appetites worldwide. . . . This book is such a tasteful narrative that it will literally make you hungry for Italian food and arouse your appetite for gastronomical history."--Don Oldenburg, USA Today. "Italian

restaurants--some good, some glitzy--far

outnumber their French rivals. Many of

these establishments are zestfully described

in How Italian Food Conquered the World, an

entertaining and fact-filled chronicle by

food-and-wine correspondent John F.

Mariani."--Aram Bakshian Jr., Wall Street

Journal.

"Equal parts

history, sociology, gastronomy, and just

plain fun, How Italian Food Conquered the

World tells the captivating and delicious

story of the (let's face it) everybody's

favorite cuisine with clarity, verve and

more than one surprise."--Colman Andrews,

editorial director of The Daily

Meal.com. "A fantastic and fascinating

read, covering everything from the influence

of Venice's spice trade to the impact of

Italian immigrants in America and the

evolution of alta cucina. This book will

serve as a terrific resource to anyone

interested in the real story of Italian

food."--Mary Ann Esposito, host of PBS-TV's

Ciao

Italia. "John Mariani has written the

definitive history of how Italians won their

way into our hearts, minds, and

stomachs. It's a story of pleasure over

pomp and taste over technique."--Danny Meyer,

owner of NYC restaurants Union Square

Cafe, The Modern, and Maialino.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Everett Potter's Travel Report:

Everett Potter's Travel Report:

Eating Las Vegas

JOHN CURTAS has been covering the Las Vegas

food and restaurant scene since 1995. He is

the co-author of EATING LAS VEGAS – The 50

Essential Restaurants (as well as

the author of the Eating Las Vegas web site: www.eatinglasvegas.

He can also be seen every Friday morning as

the “resident foodie” for Wake Up With the

Wagners on KSNV TV (NBC) Channel 3 in

Las Vegas.

Eating Las Vegas

JOHN CURTAS has been covering the Las Vegas

food and restaurant scene since 1995. He is

the co-author of EATING LAS VEGAS – The 50

Essential Restaurants (as well as

the author of the Eating Las Vegas web site: www.eatinglasvegas.

He can also be seen every Friday morning as

the “resident foodie” for Wake Up With the

Wagners on KSNV TV (NBC) Channel 3 in

Las Vegas.

MARIANI'S VIRTUAL GOURMET

NEWSLETTER is published weekly. Publisher: John Mariani. Editor: Walter Bagley. Contributing Writers: Christopher Mariani,

Robert Mariani, Misha Mariani, John A. Curtas, Gerry Dawes, Geoff Kalish,

and Brian Freedman. Contributing

Photographer: Galina Dargery. Technical

Advisor: Gerry

McLoughlin.

If you wish to subscribe to this

newsletter, please click here: http://www.johnmariani.com/subscribe/index.html

© copyright John Mariani 2020