MARIANI’S

Virtual Gourmet

October

25, 2020

NEWSLETTER

ARCHIVE

.jpg)

❖❖❖

IN THIS ISSUE

A GREAT CITY IS MADE

TO STROLL FOREVER

By John Mariani

NEW YORK CORNER

LOVE AND PIZZA

CHAPTER THIRTY-ONE

By John Mariani

NOTES FROM THE WINE CELLAR

THE SPARKLING WINES OF TRENTINO

By John Mariani

❖❖❖

A GREAT CITY IS ONE WHERE

YOU CAN STROLL FOREVER

By John Mariani

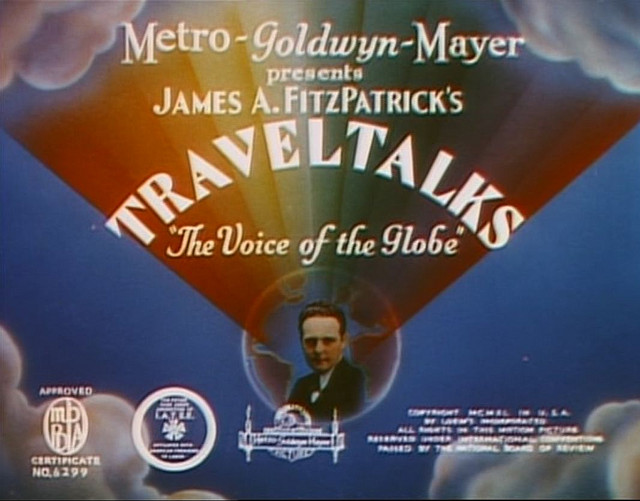

As

people discover the renewed joys of taking a

long walk during this pandemic crisis, I doubt

there is anyone who is not daydreaming about

places they have been or may now never get to. I

have been watching some of the travel shows on

TV with a different cast of mind, including one

of those old MGM “Traveltalks” shorts from the

1930s hosted by the “Voice of the Globe,” James

A. Fitzpatrick, who always ended his ten-minute

travelogues saying of every destination, “And so

we reluctantly say goodbye to . . . .”

The

cinematography, though in Technicolor, was not of

the highest quality, and no topic was dwelt on for

more than a few seconds, but the series presented

the charms of places most Americans would never

have otherwise had a glimpse of, much less travel

to. World War II put a big crimp in Fitzpatrick’s

foreign travel, but he thereupon exuded as much

enthusiasm over “Old New Orleans” and “Mighty

Niagara” as he had over “Picturesque Udaipur” and

“Serene Siam.”

The

cinematography, though in Technicolor, was not of

the highest quality, and no topic was dwelt on for

more than a few seconds, but the series presented

the charms of places most Americans would never

have otherwise had a glimpse of, much less travel

to. World War II put a big crimp in Fitzpatrick’s

foreign travel, but he thereupon exuded as much

enthusiasm over “Old New Orleans” and “Mighty

Niagara” as he had over “Picturesque Udaipur” and

“Serene Siam.”

As I watched “Beautiful Budapest” (below)

a city I adore for its beauty, its museums,  its

food and its lay-out on both sides of the Danube

River, I realized that all great cities, and many

smaller ones, are those where strolling for hours

down grand boulevards like the Champs Élysées or

the National Mall in Washington is key to finding

what makes them endlessly fascinating, again and

again, so that we always want to return to retrace

our old steps and set out on new ones.

its

food and its lay-out on both sides of the Danube

River, I realized that all great cities, and many

smaller ones, are those where strolling for hours

down grand boulevards like the Champs Élysées or

the National Mall in Washington is key to finding

what makes them endlessly fascinating, again and

again, so that we always want to return to retrace

our old steps and set out on new ones.

The narrow streets of Florence will

suddenly open onto a vast piazza like San Lorenzo,

Signoria, Strozzi, del Duomo; a stroll along New

York’s Museum Mile brings you past Central Park

and its Children’s Zoo, flanked by the

Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Guggenheim, the

Frick Collection, the Africa Center, El Museo del

Barrio, Museum of the City of New York, the Jewish

Museum, the Cooper Hewitt, the Neue Gallerie and

the National Academy Museum. A stroll along the

Chicago River (below) will be an instant

education in American architecture, from the

Tribune Tower and Merchandise Mart to the Harry

Weese  River Cottages

and Erie Park. Boston’s two-and-a-half-mile

Freedom Trail winds through the city showing the

most important locations of the burgeoning

Republic, from King’s Chapel and Park Street

Church to the Boston Massacre Site and the Old

North Church, where the lamps were lighted to send

Paul Revere on his famous ride.

River Cottages

and Erie Park. Boston’s two-and-a-half-mile

Freedom Trail winds through the city showing the

most important locations of the burgeoning

Republic, from King’s Chapel and Park Street

Church to the Boston Massacre Site and the Old

North Church, where the lamps were lighted to send

Paul Revere on his famous ride.

Easily as wonderful and diverse are

neighborhoods like Trastevere in Rome, Montmartre

in Paris, Soho in London, Buenos Aires’s Italian

section called La Boca and the sprawling night

markets of Taipei. You can follow Leopold Bloom’s

footsteps from James Joyce’s Ulysses

in Dublin, Hemingway’s haunts on Montparnasse,

even film locations in New York from the movie Goodfellas.

There are always streets lined with

boutiques, food shops, cafés, artisan shops, bars

and nightclubs. In Toledo (below) you can

stand across from the landscape El Greco so

famously painted of the Spanish city, in Berlin

walk along the remains of the graffiti-painted

Wall and in Quebec City stand on the Plains of

Abraham, where the British took the city from the

French..jpg)

Walking up impossibly steep streets in San

Francisco, finding Juliet’s balcony in a cul de

sac in Verona and stopping for coffee and

schnitzel on Vienna’s Ringstrasse make for

indelible memories. And you realize after

returning home that you’ve only scratched the

surface of a city. In each, everyone visits the

top sights—the Eiffel Tower, the Statue of

Liberty, Trafalgar Square and so on—but few get to

the lesser known attractions that a great city

offers in dizzying array, like Paris’s flea

markets called Les Puces, the quarter around the

Istanbul Bazaar and Milan’s bustling Navigli

neighborhood along the river.

Such a bounty of cultural

riches, reached largely on foot, day after day,

hour after hour, is what makes a city great, while

other cities, however large, work against the idea

of extensive, slow walking. Every city has its

street-side attractions—the bizarre extravagance

of Las Vegas’s Strip, the Indian Market of Santa

Fe, the waterfront of San Juan and painted

boulevard of Copacabana in Rio (left). But

once walked through, there are only a very limited

number of streets or neighborhoods in those cities

one can traverse on foot. Cities like Atlanta, Los

Angeles, Denver, Houston and Phoenix (all with

first-rate, if few, museums) are so spread out by

design that there is nowhere to go beyond the

downtown center, which in many of those cities are

the dreariest part.

Such a bounty of cultural

riches, reached largely on foot, day after day,

hour after hour, is what makes a city great, while

other cities, however large, work against the idea

of extensive, slow walking. Every city has its

street-side attractions—the bizarre extravagance

of Las Vegas’s Strip, the Indian Market of Santa

Fe, the waterfront of San Juan and painted

boulevard of Copacabana in Rio (left). But

once walked through, there are only a very limited

number of streets or neighborhoods in those cities

one can traverse on foot. Cities like Atlanta, Los

Angeles, Denver, Houston and Phoenix (all with

first-rate, if few, museums) are so spread out by

design that there is nowhere to go beyond the

downtown center, which in many of those cities are

the dreariest part.

Not

only because of the heat but because of the

sterility of the massive high-rises that line the

broad avenues of Dubai (below) and Abu

Dhabi does a ten-minute walk seem more than enough

before heading for the air-conditioned indoor

shopping malls. Brazil’s capital, Brasilia, has

its Monumental  Axis park, but

little else to make you want to walk around the

city. And most of the old neighborhoods have been

razed in Chinese cities dating back millennia.

Axis park, but

little else to make you want to walk around the

city. And most of the old neighborhoods have been

razed in Chinese cities dating back millennia.

Most of these cities have been planned

according to modern ideas of architecture and

civic hubris by which size and scope blots out

history and charm. In New York, narrow set-backs

have meant less and less light enters into midtown

Manhattan any more. Los Angeles was built around a

mouse maze of a Freeway system rather than to

benefit neighborhoods, so that it is still

maddening to traverse Malibu to downtown L.A. west

to east, because the roads were not built to do

so. Even Paris has ringed its historic core with

buildings that are not only cookie-cutter ugly but

bear no relation to traditional Parisian culture

and offer no reason to walk through them unless

one works there. And London’s new business center,  Canary

Wharf (below), might as well be located in

Dallas. It

should be noted that the Paris we know today was

the result of razing vast swathes of old Gothic

neighborhoods by Baron Haussmann, and there is

almost nothing left of pre-19th century New York

downtown.

Canary

Wharf (below), might as well be located in

Dallas. It

should be noted that the Paris we know today was

the result of razing vast swathes of old Gothic

neighborhoods by Baron Haussmann, and there is

almost nothing left of pre-19th century New York

downtown.

Some years ago, I exited what

was then called the Beverly Wilshire Hotel, and,

having exhausted all the commercial attractions of

downtown Beverly Hills, I strolled up into the

residential section of the city, whose eerie quiet

was broken only by the sounds of sprinklers

whooshing back and forth across perfectly groomed

lawns. I was dressed in shorts and a tennis shirt,

when suddenly I heard the whoop! whoop!

of a police car. It stopped next to me, its lights

still flashing, and two Beverly Hills cops

(neither of whom looked like Eddie Murphy in the

movie) got out and asked me for identification. I

said I wasn’t carrying any because I was just taking a

walk! Had I been an African-American I’m

sure the cops would have pushed me up against

their car and frisked me. They did not—not much

space to hide a gun in my outfit—but they were very suspicious of anyone who would take a walk

through Beverly Hills, as if the people who lived

there no longer had use of their lower limbs and

were all lifted into limos to go anywhere. Perhaps

they assumed I was casing the mansions with an eye

to breaking into them at eleven in the morning.

They let me go with a suggestion I don’t try taking a walk

through the neighborhood ever again.

were very suspicious of anyone who would take a walk

through Beverly Hills, as if the people who lived

there no longer had use of their lower limbs and

were all lifted into limos to go anywhere. Perhaps

they assumed I was casing the mansions with an eye

to breaking into them at eleven in the morning.

They let me go with a suggestion I don’t try taking a walk

through the neighborhood ever again.

The incident made me realize what a

soul-less city it was, a place where nobody walks

anywhere, a city where going to a supermarket or

dry cleaners three blocks away is reason to get in

a car and drive there and where anyone walking

through the neighborhood should be eyed with

suspicion with 911 on speed dial.

That’s not the way it is in a city where

everyone walks or bicycles everywhere

to buy a loaf of bread, meet a friend for lunch or

pick up one’s children from school. That’s not the

way it is when people lean out their windows

throughout the day and evening to chat with

friends across the way, keep an eye on things and

watch the passing parade.

I miss

all this very much during this damnable pandemic,

and I’m very glad I live in a neighborhood (albeit

in the ‘burbs) where I can walk to everything,

wave to people I know and don’t know, and feel

that no cop’s car will be bearing down in me.

❖❖❖

By John Mariani

LOVE AND PIZZA

Since, for the time being, I am unable to write about or review New York City restaurants, I have decided instead to print a serialized version of my (unpublished) novel Love and Pizza, which takes place in New York and Italy and involves a young, beautiful Bronx woman named Nicola Santini from an Italian family impassioned about food. As the story goes on, Nicola, who is a student at Columbia University, struggles to maintain her roots while seeing a future that could lead her far from them—a future that involves a career and a love affair that would change her life forever. So, while New York’s restaurants remain closed, I will run a chapter of the Love and Pizza each week until the crisis is over. Afterwards I shall be offering the entire book digitally. I hope you like the idea and even more that you will love Nicola, her family and her friends. I’d love to know what you think. Contact me at loveandpizza123@gmail.com

—John Mariani

To read previous chapters go to archive (beginning with March 29, 2020, issue.

LOVE AND PIZZA

Cover Art By Galina Dargery

CHAPTER THIRTY-ONE

Giancarlo’s

driver

arrived promptly at two o’clock and they were

outside the city on the A4 before the rush

hour hit. Less than two hours later the car

turned onto the A21 towards Alba, skirted the

town and headed into the foothills that give

Piemonte its name.

They

passed dozens of vineyards with names vaguely

familiar to Nicola—she’d been trying to learn

more about the wines of the region—then drove

down a long country road lined with cypress

trees and vineyards, finally coming into view of

the Cavallacci villa on a rise.

They

passed dozens of vineyards with names vaguely

familiar to Nicola—she’d been trying to learn

more about the wines of the region—then drove

down a long country road lined with cypress

trees and vineyards, finally coming into view of

the Cavallacci villa on a rise.

Nicola did a little research on the

property and found that its original structure

dated back at least three centuries before the

Cavallaccis obtained the villa in the 19th

century. The structure looked to be in splendid

shape, the grounds well landscaped but without

the kind of geometric layout found in larger

villas like Rome’s Tivoli. Nor was it one of the

sober-looking neo-classical 16th century villas

built by Andrea Palladio in Veneto.

Villa Cavallacci was more rustic, though

highly refined, more an extravagant, three-story

farmhouse set on a lake than a pillared

residence with lavish landscaping. Given

the Cavallaccis’ holdings in stone and marble,

the surfaces of the villa were of superb quality

and kept in pristine condition—certainly a fine

advertisement for the company to anyone

visiting.

The driver pulled up to the front of the

villa, where Nicola was received by a man and

woman of the staff, welcoming her and taking her

bag, then showing her to her room, which was

about four times the size of her dorm room and

decorated in a restrained décor of ceiling

beams, painted tile floors, a sofa, antique

writing desk and a bed covered with very fine

linens and a satin cover. The bathroom was not

huge but very well appointed in marble. There

were two paintings on the wall, both from the

late Middle Ages, their backgrounds in gold

leaf.

There was a knock on the open door and

the woman who’d received Nicola entered,

carrying a bowl of fruit and fresh roses. She

asked if Nicola wanted the windows opened,

Nicola nodded, and soon the smell of vineyard

land blew through the room to mingle with the

perfume of the roses.

Nicola was puzzled as to why she had not

yet met any members of the Cavallacci family,

so, in Italian, she asked the maid, “Is the

Cavallacci family here yet?”

The woman said that only the marchese and

his wife were on the premises at the moment but

that the others would be arriving later or the

next day for the party. This report caused

Nicola further puzzlement as to why the

Cavallaccis had not welcomed her in person. Then

she thought that perhaps the old marchese was

not well that day and that his wife was tending

to him in another part of the villa.

So, she decided, there was

nothing more to do than to tour the property

until she was introduced to the family. As she

left the front door and began walking towards

the vineyards, she heard the double honk of a

car horn. A

low-slung red Alfa Romeo pulled up and Giancarlo

bounded out of it, running to Nicola, taking her

in his arms and saying how thrilled he was to

have her at his family home.

After a few more words of welcome, he

asked, “Have you met my mother and father yet?”

Nicola shook her head and said, “No, but

I was told they’re here.”

This surprised Giancarlo, who grimaced

slightly and said, “Well, perhaps my father is

not feeling well today. I’m

sure they will be out to meet you soon.”

At that, the couple heard a woman at the

front door cry, “Giancarlo! Caro!

Bentornato!”

It was the marchesa, whose Austrian blood

showed clearly in both her height and coloring,

her silver-white hair pulled back in a ponytail. She

was dressed casually but with definite care—a

butter yellow blouse, tailored pleated tan

slacks and soft brown loafers.

Giancarlo brought Nicola over to his

mother, whom he kissed on both cheeks then said,

“Mamma,

permettetemi di introdurre mia amica Nicola

Santini.”

Nicola put out her hand, which was taken

by the marchesa, who spoke Italian with just the

slightest German accent.

“I understand you speak Italian, Signorina?”

“Yes,” said Nicola, “My father’s people

were from the Abruzzi and my mother’s from

Campania.”

All the marchesa responded was, “Ah,”

then began speaking with Giancarlo, telling him

his father was not too well that day, resting up

for his birthday party tomorrow. “I

don’t think he will be at dinner tonight, but

he’s basically all right. Will you two be

joining us for dinner?”

“Ah, I would love to, Mamma,” said

Giancarlo, sounding like a little boy, “but I

promised Nicola I would take her to dinner in

Torino—she’s never been there. I hope you don't

mind.”

The marchesa gave a little shrug and

said, “Well, if you promised to take la

signorina to Torino, I suppose there’s

nothing I can do.”

Nicola ascribed the marchesa’s coolness

both to her Austrian bloodlines and to her

taking offense that her darling son would not

stay for dinner.

It occurred to Nicola that perhaps the

marchesa had not seen her son for a while.

The

marchesa smiled at Nicola and said, now speaking

English, “Well, then, I will see you tomorrow

for the party. Buona sera.”

The

marchesa smiled at Nicola and said, now speaking

English, “Well, then, I will see you tomorrow

for the party. Buona sera.”

Nicola looked at Giancarlo with concern. He

took her by the arm and said, “Don’t

worry. She’s

disappointed we won’t dine with her, but she’ll

be very busy with preparing for tomorrow and

will forget all about us.” Then

Nicola remembered what Catherine had said about

impressing the family and didn’t think things

were off to a good start.

During the hour’s drive to Turin, Nicola

showed sincere interest in the villa’s history,

and Giancarlo knew a great deal about it, having

been educated and appointed to carry on the

family name and its holdings. Again he told

Nicola that his interests did not lie in

becoming the industrial titan his father saw him

as but that his fealty to his family ran very

deep.

Giancarlo then provided a few insights

into the city of Turin, saying, “Not

even the Italians know Turin. They only know

FIAT! FIAT! FIAT!

This is not necessarily a bad thing,

however, because not many tourists go there, so

the city is never noisy, never crowded. So, we

Torinesi have our restaurants and caffés all to

ourselves most of the time.”

He then noted that, despite the city’s

industrial image, director Michelangelo

Antonioni used Milan in La Notte,

Rome in L’Eclisse

and Ravenna in Il Deserto

Rosso—not Turin—to depict the deadening

effect of industrialization on the soul of

modern Italy.

As they drove into the center of the

city, Nicola marveled at the long, graceful,

justly famous series of arcades, the grandeur of

its vast piazzas, and its stately and highly

efficient grid pattern. Giancarlo took her

for a brief tour, past Victor Emmanuel II’s high

baroque Royal  Palace

and the splendid Duomo of St. John the Baptist.

Palace

and the splendid Duomo of St. John the Baptist.

Giancarlo turned

into the beautiful Piazza Carmignano and parked

the Alfa. Dinner that evening was at Ristorante

Del Cambio, a grand dining salon in the league

of Savini in Milan, and was obviously chosen

because the Cavallacci family had been going

there for generations—perhaps since the

restaurant opened back in 1757. Since

then it had entertained Casanova,

Cavour, and Goldoni, and 19th century society

adopted it as requisite for a visit to Turin.

Yet by 1985 the restaurant had seen

better days, its kitchen had grown tired, the

dovetail coated wait staff geriatric and its

historic furnishings—Neoclassical wood paneling,

paintings on glass by Bonelli, and baroque

stuccos—looked worn and lacked the luster that

ever would have drawn someone like Nicola and

her friends.

The young couple was, of course, given

the Cavallacci’s usual table, although the place

had so few guests that night—none of them under

fifty—they might have sat anywhere they pleased. Nicola

opened the menu, which was a balance of

continental and Piemontese cuisines, but she

left the choice to Giancarlo, who had his

favorite dishes, which included Del Cambio’s

signature risotto

alla Cavour,  cooked in

white wine, with a poached egg and Parmigiano to

enrich it. They also enjoyed delicately flavored

cannelloni

stuffed with cauliflower, and stinco di

vitello, a succulent and tender shank of

veal braised in vegetables and wine. With their

meal Giancarlo had chosen a fine Piedmont Barolo

from an old producer named Pio Cesare.

cooked in

white wine, with a poached egg and Parmigiano to

enrich it. They also enjoyed delicately flavored

cannelloni

stuffed with cauliflower, and stinco di

vitello, a succulent and tender shank of

veal braised in vegetables and wine. With their

meal Giancarlo had chosen a fine Piedmont Barolo

from an old producer named Pio Cesare.

Oddly, the conversation at the table

seemed a bit staid to Nicola, which she

attributed to the hushed ambiance of a room

three-quarters empty. Giancarlo

didn't need to ask for the bill, of course, so

after finishing their wine he said, “We’re not

going to have dessert here. I want to take you

to Torino’s most beautiful caffé, Baratti e

Milano" (below).

The

couple left arm in arm under a three-quarter

moon, walking easily to Piazza Castello (above)

under the caress of the city’s archways. When

they got within ten yards of the caffé, they

could already smell the aroma of coffee and

chocolate.

When they entered they found just about

every table occupied, but Giancarlo said he

preferred to stand at the bar and have his

coffee and dessert.

The room was tantalizing to Nicola,

everything Del Cambio was not. She listened to

the music of the Piemontese dialect being spoken

and watched the white-coated barristas

grind, pack, adjust, steam,  fizz, and

present their handiwork in a manifestation of

Turin’s deeply ingrained coffee culture, richer

than anywhere else in coffee-obsessed Italy. The

thunder of the shuddering coffee machine, the

clink of the cups and saucers hitting the

mahogany bar and the tinkle of the little spoons

in the saucer never let up. The barristas

poured a glass of Asti spumante for some, a

tipple of vermouth—a spirit invented in Turin—or

a dark, bittersweet amaro

digestiva for others. Giancarlo ordered a

slice of sugar-dusted cake covered with satiny

dark chocolate, with a filling of gianduja,

the chocolate-and-hazelnut cream that was also

created in Turin.

fizz, and

present their handiwork in a manifestation of

Turin’s deeply ingrained coffee culture, richer

than anywhere else in coffee-obsessed Italy. The

thunder of the shuddering coffee machine, the

clink of the cups and saucers hitting the

mahogany bar and the tinkle of the little spoons

in the saucer never let up. The barristas

poured a glass of Asti spumante for some, a

tipple of vermouth—a spirit invented in Turin—or

a dark, bittersweet amaro

digestiva for others. Giancarlo ordered a

slice of sugar-dusted cake covered with satiny

dark chocolate, with a filling of gianduja,

the chocolate-and-hazelnut cream that was also

created in Turin.

The couple’s conversation had picked up,

they were laughing, and Nicola took pleasure in

wiping a smudge of gianduja from

Giancarlo’s lips.

During the drive home there was a quiet

both young people seemed to welcome. Nicola had

hoped they might stay over at the Cavallaccis’

house in Turin, but as Giancarlo drove out of

the city she seemed resigned to spending the

night in separate bedrooms back at the villa. So

that by midnight their night was ending.

Standing outside in the villa’s vineyards,

embracing and kissing in the moonlight, Nicola

asked when they would be truly together for an

entire night.

“It’s impossible while we are here with

my family,” said Giancarlo. “But soon, Nicolina.

I promise.”

Neither slept well that

night.

© John Mariani, 2020

An Interview with Casa Monfort's Winemaker

By John Mariani

Italy’s

mountainous province of Trentino, usually

linked with Alto Adige, is in the extreme

northeast of the country, bordering Lombardy

and the Veneto as well as Austria, so it

shares in all those cultures’ history and

language. Indeed, many of the region’s

best-known dishes, like Spätzle, Graukäse

cheese, Speck bacon and Zelten Christmas cake

have German-Austrian names. So, too the

region’s wines overlap with the others’, with

Gewürztraminer, Sylaner and Riesling among the

varietals.

Trentino has its own

large DOC zone, but its wines have yet to

achieve the worldwide reputation of other

regions like Tuscany and Piedmont. Cantine

Monfort is one of the area’s

finest producers, with four generations of

family passion behind it. They are fine

examples of dedication to the particular

terroir. To find out more about their wines

and about Trentino’s reputation in the

modern market, I interviewed winemaker and

family scion Federico Simoni.

Lorenzo, Federico and Chiara Simoni

1. Can you tell me more about the particular terroir of Trentino?

Trentino is a small mountainous province located in Northern Italy (70% of the surface is above 1,000 meters of altitude!). Viticulture takes place in the valleys surrounded by the Dolomite mountains where the soil—a unique result of diverse geology, and Mediterranean and Alpine climate—strongly influences the grapes. In particular, our Trentodoc from Cantine Monfort is born in the vineyards located in Val dell'Adige, Val di Cembra and in Valsugana at an altitude between 200 and 900 meters above the sea level. Here you’ll find significant diurnal temperature variations, giving grapes aromatic complexity, elegance and freshness and with terroir that is rich in limestone with a high siliceous component.

2. Do the wines share anything in common with Austrian-German wines?

From a tasting point of view, the wines of Trentino represent a bridge between the Latin world and the world of Austria-Germany. We combine both the pleasantness and sweetness of the Mediterranean but also the verticality typical of Nordic wines. These are the wines that best represent Trentodoc. From a historical point of view, we have a long history and strong influence from the German wine culture and I think that the most important legacy for us oenologists from Trentino was the famous school of oenology, the now called Edmund Mach Foundation, founded by the Austro-Hungarian Empire in 1874.

3. Can you tell the similarities of your sparkling wines with Champagne, Piemonte sparkling wines and Prosecco?

Trentodoc was born from the intuition of Giulio Ferrari in the early 20th century. In fact, after having worked in France, he began the production of metodo classico in Trentino. Today, following in the footsteps of this famous pioneer, the Trentodoc denomination allows for the use of four varieties: Chardonnay, Pinot Nero, Pinot Bianco and Meunier, and guarantees second fermentation in the bottle. Trentodoc is like Champagne in this way, and the shared classic method is a commitment to make wine of the upmost quality. The similarity I find with Prosecco and Piedmont sparkling wines is the “Italianness” of the final result: our Italian way of putting boundless passion and creativity into the things we do.

4. Your wines spend a good deal of time on the lees. What is the purpose of this method?

Thanks to the research by the Edmund Mach Foundation (in addition to the school there is a lot of research!), they discovered that the contact with the lees following the second fermentation in the bottle increases both the number of aromatic molecules and their quantity, which continues to develop over time. Here we can enjoy a Trentodoc aged for a long time on the lees as well as those disgorged after extraordinary lengths of time, both types showing a different evolution and maturity. In this regard, we will shortly propose our first Monfort Rare Vintage 2008, disgorged in January 2020 after 11 years of aging on the lees. Just a few bottles that demonstrate that aging on the lees is good.

5. What is your own background as a winemaker?

I grew up in the family business and was raised right in the vineyards. I was lucky enough to have a dad who was able to let me do it, let me make mistakes and thus learn from my mistakes. During my studies at the Istituto di San Michele and immediately afterwards I had internship experiences that helped me a lot: Fontodi (Tuscany), Albrecht-Kiessling (Germany), Château Margaux (France) and Spy Valley (New Zealand ). No experiences with metodo classico but all based on the high quality wines. However, the production in the company is not entrusted only to me, but to a team of people that I respect a lot, with the senior oenologist Maurizio Iachemet, flanked by Lorenzo Pellegrini, my fellow student, also trained as an oenologist.

6. Why do you think Trentino has not gotten the same attention that other Italian regions have?

Given that Trentino represents 2% of national production, I think that after the war it has undergone numerous changes and has only began to establish itself as an area that produces high quality in the last 30 years. I’ll add that as mountain people, we are hard workers but of few words, so we have always found it difficult to describe our products. I am convinced that the new generations, who are open and traveling the world, will be able to take the baton that our parents have passed us and move forward with the development of alternative techniques and a different approach to the market.

7. How many different sparkling wines do you make?

Cantine Monfort produces three Trentodoc: base, reserva and rosé. Starting from the latter, the Trentodoc Monfort Rosè is a product that was introduced with the 2008 harvest. We immediately understood that we liked to make rosè. We seek its maximum expression in elegance, and the consumer continues to appreciate it more. This 2020 ends with the presentation of Monfort Cuvée '85, a Trentodoc made from a selection of Chardonnay and Pinot Nero grapes, elevating the original recipe of the cuvée produced for the first time in 1985. Moreover, at the end of the year we’ll release, for the first time, our Monfort Rare Vintage 2008, a late disgorgement of great character. In 2021 we will start the year with the evolution of our Monfort Riserva, which will come out with a new cuvée that enhances the territory and its vertical characteristics. I cannot reveal the name yet, but in January we will be ready to start 2021 in the best way. We are also refining another Trentodoc that I am particularly fond of: our Blanc de Noir which comes from Maurizio’s old Pinot Nero vineyards in Val di Cembra, he is our senior winemaker. However, we have to be patient a little longer.

8. What are the principal wine varieties you use?

Cantine Monfort uses Chardonnay and Pinot Noir. Over the last few years, we have defined the vineyards we allocate for the various types we produce, and this is really something interesting. It surprises me every time how vineyards managed by the same winemaker, vinified by the same winemaker, give different characteristics in relation to the geological component of the soil. Very beautiful.

9. How has climate change affected Trentino?

Trentino is an area affected by climate change whose aspects of most concern that are intensely being manifested over the last 5-6 years are the very strong winds, the hailstorms that can hit large areas and the unprecedented heavy rain storms. We face global warming by raising the share of Trentino's viticulture and in this, compared to other territories, we have an advantage, but honestly, in recent years, production has become very complex.

10. How has Covid affected Trentino, its wine sales, tourism, etc.

Trentodoc is something that brings people together; you can pop a bottle of metodo classico when you want to celebrate or when you are in good company, but since the lockdown made this impossible, sales have gone down. During the summer of 2020 we recovered sales and today we are happy. At the end of October, we can only hope that the new restrictions will not affect consumption too much since the last months of the year are very important for our sales. The same thing goes for tourism. We had a record summer for the winery; in fact, many tourists, mostly Italians, literally invaded the region (lakes, excursions in the Dolomites, wine tourism). However, winter tourism linked to the numerous ski resorts throughout our Trentino is at risk. As far as exports are concerned, each country reacted differently: we have not been affected by the crisis in countries with very strong domestic consumption; indeed, in some we have also increased sales (Sweden, Germany, Holland), while in more tourist locations we have had a strong slowdown with positive signs only in recent months (for example Mexico).

ONE OF MANY THINGS

WE DOUBT GRANOLA

EVER CHANGED

"The Mentor We Miss

Most: Molly O’Neill: The writer and chef’s LongHouse

Food Scholars Program changed many a writers'

lives—and so did her granola."—Ellen Grey, Saveur

(Oct. 2020).

MOST SHOCKING HEADLINE OF THE WEEK!

"Coffee

Ice

Cream May Contain Caffeine" by Taylor Rock, DailyMeal.com

(Pct. 19, 2020)

❖❖❖

Sponsored by

Any of John Mariani's books below may be ordered from amazon.com.

The Hound in Heaven

(21st Century Lion Books) is a novella, and

for anyone who loves dogs, Christmas, romance,

inspiration, even the supernatural, I hope you'll find

this to be a treasured favorite. The story

concerns how, after a New England teacher, his wife and

their two daughters adopt a stray puppy found in their

barn in northern Maine, their lives seem full of promise.

But when tragedy strikes, their wonderful dog Lazarus and

the spirit of Christmas are the only things that may bring

his master back from the edge of despair.

The Hound in Heaven

(21st Century Lion Books) is a novella, and

for anyone who loves dogs, Christmas, romance,

inspiration, even the supernatural, I hope you'll find

this to be a treasured favorite. The story

concerns how, after a New England teacher, his wife and

their two daughters adopt a stray puppy found in their

barn in northern Maine, their lives seem full of promise.

But when tragedy strikes, their wonderful dog Lazarus and

the spirit of Christmas are the only things that may bring

his master back from the edge of despair. WATCH THE VIDEO!

“What a huge surprise turn this story took! I was completely stunned! I truly enjoyed this book and its message.” – Actress Ali MacGraw

“He had me at Page One. The amount of heart, human insight, soul searching, and deft literary strength that John Mariani pours into this airtight novella is vertigo-inducing. Perhaps ‘wow’ would be the best comment.” – James Dalessandro, author of Bohemian Heart and 1906.

“John Mariani’s Hound in Heaven starts with a well-painted portrayal of an American family, along with the requisite dog. A surprise event flips the action of the novel and captures us for a voyage leading to a hopeful and heart-warming message. A page turning, one sitting read, it’s the perfect antidote for the winter and promotion of holiday celebration.” – Ann Pearlman, author of The Christmas Cookie Club and A Gift for my Sister.

“John Mariani’s concise, achingly beautiful novella pulls a literary rabbit out of a hat – a mash-up of the cosmic and the intimate, the tragic and the heart-warming – a Christmas tale for all ages, and all faiths. Read it to your children, read it to yourself… but read it. Early and often. Highly recommended.” – Jay Bonansinga, New York Times bestselling author of Pinkerton’s War, The Sinking of The Eastland, and The Walking Dead: The Road To Woodbury.

“Amazing things happen when you open your heart to an animal. The Hound in Heaven delivers a powerful story of healing that is forged in the spiritual relationship between a man and his best friend. The book brings a message of hope that can enrich our images of family, love, and loss.” – Dr. Barbara Royal, author of The Royal Treatment.

|

The Encyclopedia of American Food and Drink by John F. Mariani (Bloomsbury USA, $35) Modesty forbids me to praise my own new book, but let me proudly say that it is an extensive revision of the 4th edition that appeared more than a decade ago, before locavores, molecular cuisine, modernist cuisine, the Food Network and so much more, now included. Word origins have been completely updated, as have per capita consumption and production stats. Most important, for the first time since publication in the 1980s, the book includes more than 100 biographies of Americans who have changed the way we cook, eat and drink -- from Fannie Farmer and Julia Child to Robert Mondavi and Thomas Keller. "This book is amazing! It has entries for everything from `abalone' to `zwieback,' plus more than 500 recipes for classic American dishes and drinks."--Devra First, The Boston Globe. "Much needed in any kitchen library."--Bon Appetit. |

"Eating Italian will never be the same after reading John Mariani's entertaining and savory gastronomical history of the cuisine of Italy and how it won over appetites worldwide. . . . This book is such a tasteful narrative that it will literally make you hungry for Italian food and arouse your appetite for gastronomical history."--Don Oldenburg, USA Today. "Italian

restaurants--some good, some glitzy--far

outnumber their French rivals. Many of

these establishments are zestfully described

in How Italian Food Conquered the World, an

entertaining and fact-filled chronicle by

food-and-wine correspondent John F.

Mariani."--Aram Bakshian Jr., Wall Street

Journal.

"Equal parts

history, sociology, gastronomy, and just

plain fun, How Italian Food Conquered the

World tells the captivating and delicious

story of the (let's face it) everybody's

favorite cuisine with clarity, verve and

more than one surprise."--Colman Andrews,

editorial director of The Daily

Meal.com. "A fantastic and fascinating

read, covering everything from the influence

of Venice's spice trade to the impact of

Italian immigrants in America and the

evolution of alta cucina. This book will

serve as a terrific resource to anyone

interested in the real story of Italian

food."--Mary Ann Esposito, host of PBS-TV's

Ciao

Italia. "John Mariani has written the

definitive history of how Italians won their

way into our hearts, minds, and

stomachs. It's a story of pleasure over

pomp and taste over technique."--Danny Meyer,

owner of NYC restaurants Union Square

Cafe, The Modern, and Maialino.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Everett Potter's Travel Report:

Everett Potter's Travel Report:

Eating Las

Vegas JOHN CURTAS has been covering

the Las Vegas food and restaurant scene

since 1995. He is the co-author of EATING LAS

VEGAS – The 50 Essential Restaurants (as

well as the author of the Eating Las

Vegas web site: www.eatinglasvegas.

He can also be seen every Friday morning as

the “resident foodie” for Wake Up With the

Wagners on KSNV TV (NBC) Channel 3 in

Las Vegas.

Eating Las

Vegas JOHN CURTAS has been covering

the Las Vegas food and restaurant scene

since 1995. He is the co-author of EATING LAS

VEGAS – The 50 Essential Restaurants (as

well as the author of the Eating Las

Vegas web site: www.eatinglasvegas.

He can also be seen every Friday morning as

the “resident foodie” for Wake Up With the

Wagners on KSNV TV (NBC) Channel 3 in

Las Vegas.

MARIANI'S VIRTUAL GOURMET

NEWSLETTER is published weekly. Publisher: John Mariani. Editor: Walter Bagley. Contributing Writers: Christopher Mariani,

Robert Mariani, Misha Mariani, John A. Curtas, Gerry Dawes, Geoff Kalish,

and Brian Freedman. Contributing

Photographer: Galina Dargery. Technical

Advisor: Gerry

McLoughlin.

If you wish to subscribe to this

newsletter, please click here: http://www.johnmariani.com/subscribe/index.html

© copyright John Mariani 2020