MARIANI’S

Virtual

Gourmet

December

20, 2020

NEWSLETTER

Founded in 1996

ARCHIVE

CHRISTMAS DINNER IN THE MOVIE "LITTLE WOMEN" (2019)

IN THIS ISSUE

A CHILD'S CHRISTMAS IN THE BRONX

By John Mariani

NEW YORK CORNER

LOVE AND PIZZA

CHAPTER 39

By John Mariani

NOTES FROM THE WINE CELLAR

LIFTING HOLIDAY SPIRITS

By John Mariani

❖❖❖

A CHILD'S CHRISTMAS IN THE BRONX

By John Mariani

Maybe it didn't snow

for Christmas every year in the Bronx back in the

'50s. But my memory of at least one perfect

snow-bound Christmas Eve makes me think it did

often enough that I still picture my neighborhood

as white as Finland in those days when I lived

along the choppy waters of the Long Island Sound.

But

for all the decorations and the visits to stores,

the Bronx Zoo and Rockefeller Center, it was the

sumptuous Christmas feasts that helped maintain our

families' links to the Old Country long after most

other immigrant traditions had faded away. Food was

always central to everyone's thoughts at Christmas,

and the best cooks in each family were renowned for

specific dishes no one else dared make.

But

for all the decorations and the visits to stores,

the Bronx Zoo and Rockefeller Center, it was the

sumptuous Christmas feasts that helped maintain our

families' links to the Old Country long after most

other immigrant traditions had faded away. Food was

always central to everyone's thoughts at Christmas,

and the best cooks in each family were renowned for

specific dishes no one else dared make.

The assumption that everything would be exactly the

same as last year was as  comforting as knowing that

Christmas Day would follow Christmas Eve. The finest

ancestral linens were ironed and smoothed into

place, dishes of hard candy were set out on every

table, and the kitchen ovens hissed and warmed our

homes for days. The reappearance of the old

dishes, the irresistible aromas, tastes and

textures, even the seating of family members in the

same spot at the table year after year anchored us

to a time and a place that was already changing more

rapidly than we could understand.

comforting as knowing that

Christmas Day would follow Christmas Eve. The finest

ancestral linens were ironed and smoothed into

place, dishes of hard candy were set out on every

table, and the kitchen ovens hissed and warmed our

homes for days. The reappearance of the old

dishes, the irresistible aromas, tastes and

textures, even the seating of family members in the

same spot at the table year after year anchored us

to a time and a place that was already changing more

rapidly than we could understand.

It's funny now to

think that my memories of the food and the dinners

are so much more intense than those of toys and

games I received, but that seems true of most

people. The exact taste of Christmas cookies, the

sound of beef roasting in its pan, and the smell of

evergreen mixed with the scent of cinnamon and

cloves and lemon in hot cider were like holy incense

in church, unforgettable, like the way you remember

your parents' faces when they were young.

It's funny now to

think that my memories of the food and the dinners

are so much more intense than those of toys and

games I received, but that seems true of most

people. The exact taste of Christmas cookies, the

sound of beef roasting in its pan, and the smell of

evergreen mixed with the scent of cinnamon and

cloves and lemon in hot cider were like holy incense

in church, unforgettable, like the way you remember

your parents' faces when they were young.

No one in our neighborhood was poor but few were

rich. Yet we mounted  feasts as lavish as any I could

imagine in a book, and in the days preceding

Christmas people took enormous joy in spending their

money on foods only eaten during that season.

feasts as lavish as any I could

imagine in a book, and in the days preceding

Christmas people took enormous joy in spending their

money on foods only eaten during that season.

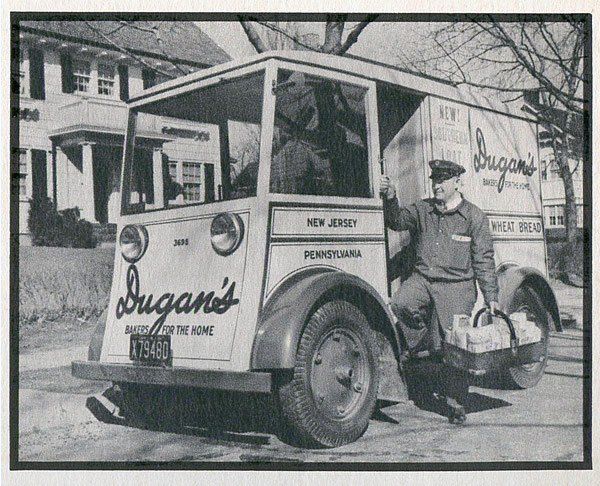

It was still a time when the vegetable man would

sell his produce from an old truck on Campbell

Drive, and Dugan's and Krug's bread men came right

to your door with special holiday cupcakes and

cookies. We'd go to Biancardi's Meats on

Arthur Avenue and, while the butcher on Middletown

Road usually carried fresh fish only on Fridays, he

was always well stocked with cod, salmon, lobsters

and eel during the holidays. The pastry shops

worked overtime to bake special Christmas breads and

cakes, which would be gently wrapped in a swaddling

of very soft pink tissue paper tied up with ribbons

and sometimes even sealed with wax to deter anyone

from opening it before Christmas.

By Christmas Eve the stores ran out of everything,

and pity the poor cook who delayed buying her

chestnuts, ricotta cheese, or fresh yeast until it

was too late. Weeks in advance the women would put

in their order at the live poultry market for a

female rabbit—not a male—or a goose that had to

weigh exactly twelve pounds.

You always knew

what people were cooking for Christmas because the

aromas hung in the hallways of the garden apartments

and the foyers of their homes— garlicky tomato

sauces, roast turkeys, rich shellfish stews, and the

sweet, warm smells of pastries and breads could make

you dizzy with hunger. When you went out into

the cold, those aromas would slip out the door and

mingle with the biting sea-salted air and the fresh

wet snow swept in off the Sound.

You always knew

what people were cooking for Christmas because the

aromas hung in the hallways of the garden apartments

and the foyers of their homes— garlicky tomato

sauces, roast turkeys, rich shellfish stews, and the

sweet, warm smells of pastries and breads could make

you dizzy with hunger. When you went out into

the cold, those aromas would slip out the door and

mingle with the biting sea-salted air and the fresh

wet snow swept in off the Sound.

At the Italian homes in the

Bronx ancient culinary rituals were followed long

after they'd lost their original religious

symbolism. The traditional meatless meal of

Christmas Eve—“La Vigilia”(left)—which began

centuries ago as a form of penitential purification,

developed into a robust meal of exotic seafood

dishes that left one reeling from the table.

According to the traditions of Abruzzi, where my father's family came from, the Christmas

Eve dinner should be composed of seven or nine

dishes—mystical numbers commemorating the seven

sacraments and the Holy Trinity multiplied by

three.

where my father's family came from, the Christmas

Eve dinner should be composed of seven or nine

dishes—mystical numbers commemorating the seven

sacraments and the Holy Trinity multiplied by

three.

This was always my Auntie Rose's shining

moment. She would cook with the zeal and energy of a

dozen nuns, beginning with little morsels of crisply

fried calamari. She made spaghetti on a

stringed utensil called a "ghitarra" and served it

with a sauce teeming with shellfish. Next came

an enormous pot of lobster fra diavolo (right)—a

powerful coalescence of tomato, garlic, onion,

saffron and hot red peppers, all spooned into soup

plates around shiny, scarlet-red lobsters that some

guests attacked with daunting, unbridled gusto while

others took their dainty time extracting every

morsel of meat from the deepest recesses of the

body, claws and legs.

Few children would eat

baccala, a strong-smelling salted cod cooked for

hours in order to restore its leathery flesh to

edibility, and stewed eel, an age-old symbol of

renewal, was a delicacy favored mostly by the

old-timers. But everyone waited for the dessert—the

yeasty, egg bread called "panettone,"

shaped like a church dome and riddled with golden

raisins and candied fruit.

Christmas Day

came too early for everyone but the children, but as

soon as presents were exchanged, my mother and

grandmother would begin work on the lavish Christmas

dinner to be served that afternoon. It was always a

mix of regional Italian dishes and American

novelties, like the incredibly rich, bourbon-laced

egg nog my father insisted on serving before my

grandmother's lasagna, in which were hidden dozens

of meatballs the size of hazelnuts. Then my mother

would set down a massive

Christmas Day

came too early for everyone but the children, but as

soon as presents were exchanged, my mother and

grandmother would begin work on the lavish Christmas

dinner to be served that afternoon. It was always a

mix of regional Italian dishes and American

novelties, like the incredibly rich, bourbon-laced

egg nog my father insisted on serving before my

grandmother's lasagna, in which were hidden dozens

of meatballs the size of hazelnuts. Then my mother

would set down a massive  roast beef,

brown and crackling on the outside, red as a

poinsettia within, surrounded by sizzling roast

potatoes and Yorkshire pudding glistening from the

fat absorbed from the beef. Dessert reverted

to venerable Italian tradition with my grandmother's

prune-and-chocolate-filled pastries and honeyed

cookies called "struffoli" (right).

And someone always brought panforte,

an intensely rich, thick Sienese fruit and nut cake

no one could eat more than a sliver of.

roast beef,

brown and crackling on the outside, red as a

poinsettia within, surrounded by sizzling roast

potatoes and Yorkshire pudding glistening from the

fat absorbed from the beef. Dessert reverted

to venerable Italian tradition with my grandmother's

prune-and-chocolate-filled pastries and honeyed

cookies called "struffoli" (right).

And someone always brought panforte,

an intensely rich, thick Sienese fruit and nut cake

no one could eat more than a sliver of.

After such a meal, we needed to go for a walk in the

cold air. In other homes up and down our block

people were feasting on Norwegian lutefisk, Swedish

meatballs, German stollen, Irish plum pudding and

American gingerbread. If you stopped and listened

for a moment, you could hear the families singing

carols in their native tongue.

By early evening

guests got ready to leave and leftovers were packed

up to take home, belying everyone's protest that

they wouldn't eat for days afterwards.

By early evening

guests got ready to leave and leftovers were packed

up to take home, belying everyone's protest that

they wouldn't eat for days afterwards.

By then the snow had taken on

an icy veneer and the wind died down to a

whisper. I remember how the cold air magnified

sounds far, far away, so as I crept into bed I could

hear the waves lapping the sea wall and the rattling

clack-clack, clack-clack of the El running from

Buhre Avenue to Middletown Road. It was a kind of

lullaby in those days, when it never failed to snow

on Christmas in the Bronx.

❖❖❖

By John Mariani

LOVE AND PIZZA

Since, for the time being, I am unable to write about or review New York City restaurants, I have decided instead to print a serialized version of my (unpublished) novel Love and Pizza, which takes place in New York and Italy and involves a young, beautiful Bronx woman named Nicola Santini from an Italian family impassioned about food. As the story goes on, Nicola, who is a student at Columbia University, struggles to maintain her roots while seeing a future that could lead her far from them—a future that involves a career and a love affair that would change her life forever. So, while New York’s restaurants remain closed, I will run a chapter of the Love and Pizza each week until the crisis is over. Afterwards I shall be offering the entire book digitally. I hope you like the idea and even more that you will love Nicola, her family and her friends. I’d love to know what you think. Contact me at loveandpizza123@gmail.com

—John Mariani

To read previous chapters go to archive (beginning with March 29, 2020, issue.

LOVE AND PIZZA

Cover Art By Galina Dargery

CAPRI

The

show the next morning went splendidly and the

audience, though not as large as that in

Milan, applauded the clothes with obvious

enthusiasm.

This time Nicola was accorded no more

nor less the applause of the other girls.

Signora

Palma profusely thanked the crowd, brought out

her girls for a last look then went back and

collapsed on a sofa. “And now,” she said, “we

wait for the orders to come in, then I sleep like a

big bear. Then, I start designing the fall

collection!”

Signora

Palma profusely thanked the crowd, brought out

her girls for a last look then went back and

collapsed on a sofa. “And now,” she said, “we

wait for the orders to come in, then I sleep like a

big bear. Then, I start designing the fall

collection!”

She shoo-ed the models away, telling them

to go have a good time, and reminded Nicola

dinner was at eight-thirty. “We go over

together,” said Signora

Palma. “Is a little trattoria not too well known

by the tourists.”

At eight-thirty—more or less—Signora

Palma, Nicola, and a few of her staff met in the

hotel lobby, had taxis hailed, and drove off to

Trattoria Benedetto, named after the patron

saint of the province. From

the outside it was fairly typical of many

trattorias on Capri—stucco outside and in,

grapevines growing up the exterior walls, a

small dining room with rustic furniture, shelves

holding wine bottles and an antipasti

table crammed with marinated vegetables, local

cheeses and salumi, and bowls of big, bumpy

bright yellow Campanian lemons. The

kitchen was half open, at waist level, and the

owner and his wife did all the ordering, wine

opening, and serving, with the help of their

bored-looking teenage son.

Signora

Palma’s dozen guests took up most of the dining

room, with tables pushed together, and she told

everyone to sit anywhere they’d like. Champagne

was opened and poured and everyone  went

to the

antipasti table to help themselves (left). After

the meager meal of the night before and with no

further modeling for the week ahead, Nicola was

good to herself, putting a little of everything

on her plate—the thinly sliced zucchini in olive

oil, caramelized onions, thin fingers of fried

eggplant, warm buffalo mozzarella that had been

made just moments before they arrived, and

various salumi.

went

to the

antipasti table to help themselves (left). After

the meager meal of the night before and with no

further modeling for the week ahead, Nicola was

good to herself, putting a little of everything

on her plate—the thinly sliced zucchini in olive

oil, caramelized onions, thin fingers of fried

eggplant, warm buffalo mozzarella that had been

made just moments before they arrived, and

various salumi.

Back at her seat, Nicola ate with gusto,

finding the food unusually delicious, perhaps

because she was so hungry. But

then, these antipasti—examples

of which she’d had many times both in Italy and

at home—possessed flavors that seemed not just

fresh but elemental. The

flavors burst upon her palate as she sipped her

Champagne.

At that point individual plates of an

appetizer were set before the guests. It was

a rendering of the quintessential Neapolitan

ingredients—tomato, ricotta, basil and olive

oil—yet the chef had taken a small tomato at the

peak of its ripeness, scooped out the insides,

replaced it with housemade ricotta laced with

Parmigiano, set a small piece of basil across

it, then topped it with the cut-off cap of the

tomato. The

confection had then been placed very briefly in

the oven so that everything warmed and the

flavors melded. Then the stuffed tomato was

placed on a bed of arugula and dotted with aged

balsamic vinegar. Everyone at the table

expressed their pleasure by variations on a

swoon, saying the dish was fantastico!

superba!

grande!

Next came the chef’s take on ziti alla

sorrentina (above), which meant it

would have a tomato and eggplant sauce. But

again, when Nicola tasted the result, it was as

if she’d never had the dish before, or at least

not with this refinement. The

spaghetti itself, made in the kitchen, was

tender and its strands entwined in a kind of

hive, each coated with a sauce whose sweetness

was pure and natural, the eggplant just soft

enough to add a creamy element to the dish,

which was lightly sprinkled with local pecorino.

Next came the chef’s take on ziti alla

sorrentina (above), which meant it

would have a tomato and eggplant sauce. But

again, when Nicola tasted the result, it was as

if she’d never had the dish before, or at least

not with this refinement. The

spaghetti itself, made in the kitchen, was

tender and its strands entwined in a kind of

hive, each coated with a sauce whose sweetness

was pure and natural, the eggplant just soft

enough to add a creamy element to the dish,

which was lightly sprinkled with local pecorino.

When that dish was

cleared, a glorious risotto was served, cooked

in tomato water, not sauce, so that it had a

tang to it that Nicola almost thought was lemon. The

seasonings were subtle, absorbed into the fat

rice kernels through careful, long stirring.

The main course was kept very simple:

each guest received a cut of barely cooked

swordfish—pesce spada (left)—on top of

which were quickly caramelized onions that had

softened then acquired a little crispness for

texture. Minced

basil looking like confetti adorned the fish,

which was given a benediction of olive oil in

which a clove of garlic had been crushed. With

the food, the guests had switched to a wine

called Taurasi from the region.

The

guests were raving about the food and Signora

Palma could not have been happier. “You see,”

she said, “I told

you the chef was un genio.

And he is also very handsome.” Turning

to the owner, she asked—well, more or less

demanded—to have the chef brought out.

A few minutes later he appeared, having

changed into a clean white chef’s jacket with

the trattoria’s name on it. The

guests applauded and Signora

Palma introduced the chef. “Signore e

signori, mi presente il maestro—Marco di

Noè!” More applause, then the young chef, who

was indeed very handsome, with blue-gray eyes

and thick hair as dark as Nicola’s. He

humbly thanked everyone, saying that it was an

honor to cook for Signora Palma,

who

demanded he sit down at her table, moving a

chair in next to Nicola.

Nicola congratulated him on a meal that

seemed so simple yet so remarkably different,

asking how he did it. The young chef shrugged,

ran his fingers through his dark hair and said “Senza

l’ultimo ingredienti, c’e niente.” Without

the best ingredients it is nothing.

Then, sensing Nicola was not Italian

asked, “You are American, yes?”

“I’m Italian-American,” she replied. “I was

born and raised in New York.”

“But your parents were Neapolitan, no? I

hear it in your accent.”

Nicola remembered the last time she had a

meal at which this topic had proven a harbinger

of disappointment.

She told Marco her father’s side of the

family was from Abruzzo, though his mother was

from Emilia-Romagna, and her mother’s side was

strictly Neapolitan, which is how Nicola had

picked up the accent.

“Plus,” she said, “most of the people in

my neighborhood in the Bronx came from Campania,

so I hear it a lot.”

“I speak the true dialect a lot around

here—I was born in Naples—though on Capri I

speak more Italian, French, Spanish, German.”

“You speak all those languages?”

“Yes, I find it easy to pick them up. Spanish

and

French are very easy for an Italian.”

Marco accepted Signora

Palma’s invitation to have a glass of Taurasi. He

thanked her for it and said, “This is the best

producer of this wine—Mastroberardino, in

Atripalda.

The family has brought back a lot of the

grape varieties that were thought to be lost.”

Nicola truly was amazed by Marco’s

fluency in English, which sounded as though he’d

learned from British teachers. The two young

people kept talking together, getting the usual

details on their backgrounds, and Marco seemed

delighted that Nicola had Neapolitan blood

running through her veins.

“So, you are a model?” he asked, not

hinting if he was impressed by or disdainful of

the profession.

“I do a little modeling, yes, but I came

to Italy last spring as part of a semester

abroad in Milan.”

“Where do you go to school?”

“Columbia University in New York.”

“Ah, I understand it is a very good

school. And

what do you study?”

“Art history, specifically the art of the

Italian Renaissance,” she said, feeling quite at

ease. “I

hope to go on for my PhD next fall.”

“Really? And how do you find the time to

model?”

“Whenever I have time, I try to take a

job.”

Marco nodded, as if to say, this seems

like a smart American girl. “Who,

may I ask, are some of your favorite Renaissance

artists?”

“Well,” said Nicola, never having been

quizzed on the subject by a cook, “the usual

great ones, da Vinci, Raphael, Donatello, but I

find I’m particularly drawn to the Venetian

artists.”

Marco continued nodding, this time

somewhat wearily. “Bellini, Carpaccio, Titian,

Tintoretto, Veronese,” he said, “and the rest.”

“Absolutely! You know the subject well.”

“But, about these Venetians. What

do you like about them?”

“Well, their coloring, the high drama,

the psychology they show in their portraits.”

Marco put up his

hands and said, “You know what Michelangelo said

about the Venetians?”

Marco put up his

hands and said, “You know what Michelangelo said

about the Venetians?”

“No, what?”

“He said they’d be much better artists if

they’d learn how to draw.”

Nicola was shocked. “Michelangelo said

that?”

Marco then launched into a well-informed

discussion of why he thought the Venetians were

inferior to the other schools of the

Renaissance, contending that it was the

Neapolitan baroque artists who had been

underrated and underappreciated.

“Like who?” asked Nicola, riffling

through her brain to think of any famous

Neapolitan artists.

“Ah, so many: Caracciolo, Rosa,

Cavallino, Sellitto, Stanzione, so many you have

probably never heard of.”

Indeed, Nicola had not, even though the

Neapolitan School was an important part of the

Italian Baroque, and she wondered at how much

Chef Marco di Noè seemed to know about it. She

was also intrigued by Marco’s being the first

man in Italy who id not immediately comment on

how beautiful she was.

“How do you know so much about these

artists?” she asked.

“Because I am not just a chef, Signorina,

I am also a painter. Not a

very good painter, but I work as a chef for the

season on Capri, then work on my painting the

rest of the time.”

“So you have a studio here on the island?

I’d love to see some of your work.”

“No, I live in Naples when I’m not here. Perhaps

you would like to visit the Museo di Capodimonte

to see the Neapolitan School, and if you have

time, some of my work. I have

some hanging in galleries in the city.”

Salvator

Rosa, "Self-Portrait."

Nicola

would

have loved at least to see the museum but told

Marco, “That would be wonderful but I have to

leave on Tuesday.”

“So,” he countered, “tomorrow is Sunday.

I can take the day off—I’ve been working seven

days a week since April and now the season is

almost over and there’s not much business. We

can take the fast ferry over, I’ll show you the

city, and we can be back in Capri in the

evening.”

Nicola gave the matter about five

seconds’ thought and said, “Marco, let’s do it. What

time?”

“Signorina

Santini—“

“Please call me Nicola.”

“Ah, prego,

Nicola. Okay, we get an early ferry out tomorrow

morning and will be in Napoli by the time the

museum opens.”

They settled on a time, and Marco said

he’d pick her up at her hotel, then taxi down to

the dock. Meanwhile

Signora

Palma’s guests were getting up and thanking both

their host and the trattoria’s owners.

“A

domani, Nicola,” said Marco.

“A

domani,” and with that Marco shook

Nicola’s hand and said goodnight.

When

Nicola

got back to her room, she turned the evening

over in her mind, trying to figure out this

chef-painter with the deferential manners. He was

obviously a superb cook and knew much more about

Neapolitan art than she did, and he seemed to be

a good enough artist to be in galleries. And he

was very handsome, to boot. A very

nice piece of work, Marco was. And

with just two days left in Italy, she was

determined to make the most of it.

Massimo Stanzione, "Judith

and Holofernes."

LIFTING HOLIDAY SPIRITS

By John Mariani

Most people, I suspect, are very true to their spirits brands, both out of familiarity and because the options have grown so large that finding yet another single malt Scotch aged in bourbon casks or vodka filtered through moon rocks rarely makes for a new preference. It is, however, fun to be a bit adventurous around the holidays, especially when including those you might want to taste something new and interesting or even something they might never have thought of drinking. Here are some new and old suggestions I’ve been enjoying.

DANO’S

TEQUILA

DANO’S

TEQUILAThe market is now overflowing with “sipping tequilas,” usually limited release añejos, but I, for one, cannot imagine myself nursing one before a roaring fire. I do, though, like the variations that make margaritas take on nuance beyond the basic blancos. The family-owned Dano’s, founded not in Mexico but in Steamboat Springs, Colorado, in 2018, shows that you can get good results using 100% agave when you depend on a distillery in Mexico dating back to 1841. I’m not a fan of flavored tequilas, like Dano’s pineapple and jalapeño, but its reposado ($53), aged for nine months in white oak barrels, is a soft tequila with complexity, and, yes, it’s perfect for a margarita.

FOS GREEK MASTIHA LIQUEUR

Greece may be well known for its resinous wines and liqueurs like licorice-tasting ouzo, but mastiha is something unusual and quite delicious. It, too, is made from a resin from the mastiha tree (known as the “crying tree”), grown only on the small Mediterranean island of Chios. Used as a flavoring in baked goods, it has only a touch of anise, as well as pine and various herbs, and it is sweet without being cloying, very good on the rocks, though it would make a nice mixer with brandy. As far as I know Fos’s bottling ($40) is the only one exported to the U.S.

STRANAHAN’S BLUE PEAK SINGLE MALT WHISKEY

It can’t be called Scotch by law, but this Colorado-based single malt, with a solera finish, comes in at 43% alcohol and has a very pleasing balance of heat and sweet undertones. I’m not sure if it makes any difference that the whiskey is “handcrafted at high altitude” or “cut to proof with pristine Rocky Mountain water,” but I like its bite and its true malt taste, without much peatiness ($50). They make six variations,

some

with higher proof; one, with the way-too-cute

name Snowflake, is only made on one day in

December each year.

some

with higher proof; one, with the way-too-cute

name Snowflake, is only made on one day in

December each year. CATOCTIN CREEK

Founded by Becky and

Scott Harris in 2009 as the first legal

distillery in Loudoun County, Virginia, since

before Prohibition, Catoctin Creek revels in

making rye, a spirit not too many years ago

relegated to the shelves near the cash

registers in liquor stores. Catoctin’s

ryes—the Indian name meant "place of many

deer"—are made in several styles, including

Roundstone ($45), made from 100% rye at 89

proof, Distiller’s Edition at 92 proof ($53),

“pulled from the back of the barn,” and the

powerhouse top-of-the-line Cask Proof ($90) at

116 proof.

I tasted and thoroughly

enjoyed the Catoctin Creek Peach Barrel

Select

80 Proof ($46).They also

make gins, brandies, fruit

brandies—even a Wolfgang Puck Rye

finished in California Zinfandel

barrels from Ravenswood. Too many,

really, when the label should stick

with its best iterations of rye it

does so impressively.

CLÉMENT CUVÉE HOMÈRE

Clément is known for its flavored

Martinique rums, like shrub, but it makes some

superior and very distinctive rums like this

cuvée from the Cellar Master’s Selection Series

culled from the highest-rated vintage rums of

the last fifteen years ($110). It is aged in

French Limousin barriques and re-charred Bourbon

barrels. It is woody, has a long finish and is

quite a bit drier than most other Caribbean

rums. And, as a gift, it comes in a beautiful

squat bottle. The name commemorates Homère

Clément, the planter who founded the distillery,

which mimicked the spirits techniques of

Armagnac, which he called Rhum Agricole.

Clément is known for its flavored

Martinique rums, like shrub, but it makes some

superior and very distinctive rums like this

cuvée from the Cellar Master’s Selection Series

culled from the highest-rated vintage rums of

the last fifteen years ($110). It is aged in

French Limousin barriques and re-charred Bourbon

barrels. It is woody, has a long finish and is

quite a bit drier than most other Caribbean

rums. And, as a gift, it comes in a beautiful

squat bottle. The name commemorates Homère

Clément, the planter who founded the distillery,

which mimicked the spirits techniques of

Armagnac, which he called Rhum Agricole. NOILLY PRAT VERMOUTH ROUGE

Why bother mentioning a red vermouth that hasn’t changed since 1813? Simply because whenever I get nostalgic for the first cocktails I ever drank five decades ago, more often than not there was red vermouth in them. I was never a Martini guy, so white vermouth held little interest for me, but I loved the red vermouth as part of the Negroni, Manhattan, Americano and Bronx cocktails. And because it was delicious all on its own, with a twist of lemon or orange, I’ve found it makes a light, herbaceous aperitif, with 29 herbs, all on its own ($12.50). There have been some feeble attempts to make new vermouths in the market, but Noilly Prat perfected theirs a long, long time ago.

AH,

THANK GOD! NOW THE WORLD CAN

AH,

THANK GOD! NOW THE WORLD CAN

SPIN ON ITS AXIS AGAIN!

It

has been widely reported on the internet that TV

chef and author Nigella Lawson has admitted she

does not know how to pronounce "microwave." Before

adding milk to boiled potatoes, she said, “A

bit of milk, full fat, which I’ve warmed in

the mee-kro-whaav-é.” Then reproached

herself saying, "Is

that how it’s supposed to be pronounced? Have I

been wrong all this time?"

BREAKING NEWS! CHAMOY AND

DUKKAH

SUPPLIES RUNNING LOW IN AMERICA!

4 Global Flavors

That Defined the Past 20 Years, according to the

McCormick Flavor Forecast:

Pumpkin Pie Spice

Turmeric

Chamoy

Dukkah

Sponsored by

Any of John Mariani's books below may be ordered from amazon.com.

The Hound in Heaven

(21st Century Lion Books) is a novella, and

for anyone who loves dogs, Christmas, romance,

inspiration, even the supernatural, I hope you'll find

this to be a treasured favorite. The story

concerns how, after a New England teacher, his wife and

their two daughters adopt a stray puppy found in their

barn in northern Maine, their lives seem full of promise.

But when tragedy strikes, their wonderful dog Lazarus and

the spirit of Christmas are the only things that may bring

his master back from the edge of despair.

The Hound in Heaven

(21st Century Lion Books) is a novella, and

for anyone who loves dogs, Christmas, romance,

inspiration, even the supernatural, I hope you'll find

this to be a treasured favorite. The story

concerns how, after a New England teacher, his wife and

their two daughters adopt a stray puppy found in their

barn in northern Maine, their lives seem full of promise.

But when tragedy strikes, their wonderful dog Lazarus and

the spirit of Christmas are the only things that may bring

his master back from the edge of despair. WATCH THE VIDEO!

“What a huge surprise turn this story took! I was completely stunned! I truly enjoyed this book and its message.” – Actress Ali MacGraw

“He had me at Page One. The amount of heart, human insight, soul searching, and deft literary strength that John Mariani pours into this airtight novella is vertigo-inducing. Perhaps ‘wow’ would be the best comment.” – James Dalessandro, author of Bohemian Heart and 1906.

“John Mariani’s Hound in Heaven starts with a well-painted portrayal of an American family, along with the requisite dog. A surprise event flips the action of the novel and captures us for a voyage leading to a hopeful and heart-warming message. A page turning, one sitting read, it’s the perfect antidote for the winter and promotion of holiday celebration.” – Ann Pearlman, author of The Christmas Cookie Club and A Gift for my Sister.

“John Mariani’s concise, achingly beautiful novella pulls a literary rabbit out of a hat – a mash-up of the cosmic and the intimate, the tragic and the heart-warming – a Christmas tale for all ages, and all faiths. Read it to your children, read it to yourself… but read it. Early and often. Highly recommended.” – Jay Bonansinga, New York Times bestselling author of Pinkerton’s War, The Sinking of The Eastland, and The Walking Dead: The Road To Woodbury.

“Amazing things happen when you open your heart to an animal. The Hound in Heaven delivers a powerful story of healing that is forged in the spiritual relationship between a man and his best friend. The book brings a message of hope that can enrich our images of family, love, and loss.” – Dr. Barbara Royal, author of The Royal Treatment.

|

The Encyclopedia of American Food and Drink by John F. Mariani (Bloomsbury USA, $35) Modesty forbids me to praise my own new book, but let me proudly say that it is an extensive revision of the 4th edition that appeared more than a decade ago, before locavores, molecular cuisine, modernist cuisine, the Food Network and so much more, now included. Word origins have been completely updated, as have per capita consumption and production stats. Most important, for the first time since publication in the 1980s, the book includes more than 100 biographies of Americans who have changed the way we cook, eat and drink -- from Fannie Farmer and Julia Child to Robert Mondavi and Thomas Keller. "This book is amazing! It has entries for everything from `abalone' to `zwieback,' plus more than 500 recipes for classic American dishes and drinks."--Devra First, The Boston Globe. "Much needed in any kitchen library."--Bon Appetit. |

"Eating Italian will never be the same after reading John Mariani's entertaining and savory gastronomical history of the cuisine of Italy and how it won over appetites worldwide. . . . This book is such a tasteful narrative that it will literally make you hungry for Italian food and arouse your appetite for gastronomical history."--Don Oldenburg, USA Today. "Italian

restaurants--some good, some glitzy--far

outnumber their French rivals. Many of

these establishments are zestfully described

in How Italian Food Conquered the World, an

entertaining and fact-filled chronicle by

food-and-wine correspondent John F.

Mariani."--Aram Bakshian Jr., Wall Street

Journal.

"Equal parts

history, sociology, gastronomy, and just

plain fun, How Italian Food Conquered the

World tells the captivating and delicious

story of the (let's face it) everybody's

favorite cuisine with clarity, verve and

more than one surprise."--Colman Andrews,

editorial director of The Daily

Meal.com. "A fantastic and fascinating

read, covering everything from the influence

of Venice's spice trade to the impact of

Italian immigrants in America and the

evolution of alta cucina. This book will

serve as a terrific resource to anyone

interested in the real story of Italian

food."--Mary Ann Esposito, host of PBS-TV's

Ciao

Italia. "John Mariani has written the

definitive history of how Italians won their

way into our hearts, minds, and

stomachs. It's a story of pleasure over

pomp and taste over technique."--Danny Meyer,

owner of NYC restaurants Union Square

Cafe, The Modern, and Maialino.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Everett Potter's Travel Report:

Everett Potter's Travel Report:

Eating Las Vegas JOHN

CURTAS has been covering the Las Vegas food and

restaurant scene since 1995. He is the co-author

of EATING LAS

VEGAS – The 50 Essential Restaurants (as

well as the author of the Eating Las Vegas

web site: www.eatinglasvegas.

He can also be seen every Friday morning as the

“resident foodie” for Wake Up With the Wagners

on KSNV TV (NBC) Channel 3 in Las Vegas.

Eating Las Vegas JOHN

CURTAS has been covering the Las Vegas food and

restaurant scene since 1995. He is the co-author

of EATING LAS

VEGAS – The 50 Essential Restaurants (as

well as the author of the Eating Las Vegas

web site: www.eatinglasvegas.

He can also be seen every Friday morning as the

“resident foodie” for Wake Up With the Wagners

on KSNV TV (NBC) Channel 3 in Las Vegas.

MARIANI'S VIRTUAL GOURMET

NEWSLETTER is published weekly. Publisher: John Mariani. Editor: Walter Bagley. Contributing Writers: Christopher Mariani,

Robert Mariani, Misha Mariani, John A. Curtas, Gerry Dawes, Geoff Kalish,

and Brian Freedman. Contributing

Photographer: Galina Dargery. Technical

Advisor: Gerry

McLoughlin.

If you wish to subscribe to this

newsletter, please click here: http://www.johnmariani.com/subscribe/index.html

© copyright John Mariani 2021