MARIANI’S

Virtual

Gourmet

December

27, 2020

NEWSLETTER

NEWSLETTER

NEWSLETTER

HAPPY NEW YEAR!

❖❖❖

IN THIS ISSUE

TURIN, HIDING IN PLAIN SIGHT

By John Mariani

NEW YORK CORNER

LOVE AND PIZZA

CHAPTER FORTY

By John Mariani

NOTES FROM THE WINE CELLAR

SO YOU WANT TO RUN A WINE TASTING

By John Mariani

❖❖❖

TURIN, HIDING IN PLAIN SIGHT

By John Mariani

“Not even the

Italians know Turin!

They only know FIAT! FIAT! FIAT!”

So said

Michele, a spry, elegant,

elderly Turinese who took my wife and me for a cup

of rich, bittersweet coffee

and chocolate called a “capriccio”

at

the historic Caffè Baratti e Milano, opened in

1875 on Turin’s broad Piazza

Castello. We’d

met him just minutes

before on our search for the equally famous café

named Bicerin, only to learn

from Michele that it was closed on Wednesdays.

He

didn’t seem troubled by his

statement that the world outside of Piedmont,

including the rest of Italy, did

not regard his hometown as worth visiting, unless

it was to see the Automobile

Museum. “It

is not a bad thing not to

have so many tourists,” said Michele, who had a

salt-and-pepper beard and wore

an artfully thrown scarf around his shoulders. He

never gave us his last name

and seemed to have retired to the life of a

boulevardier known to every

bartender and barrista

in Turin.

He

didn’t seem troubled by his

statement that the world outside of Piedmont,

including the rest of Italy, did

not regard his hometown as worth visiting, unless

it was to see the Automobile

Museum. “It

is not a bad thing not to

have so many tourists,” said Michele, who had a

salt-and-pepper beard and wore

an artfully thrown scarf around his shoulders. He

never gave us his last name

and seemed to have retired to the life of a

boulevardier known to every

bartender and barrista

in Turin.

These days,

as Covid keeps the lid

on tourism in Italy, visitors are fewer than ever.

“Look around

you,” he said,

smiling. “Turin is never noisy, never crowded,

except”—his eyes rolled

back—“during those Winter Olympics! So we Turinesi

have our restaurants and

cafés all to ourselves most of the time.

Our Mercato sells every kind of food and

wine you could possibly want,

and the original EATaly is just a few kilometers

that way.” He waved his hand

in the general direction of the gargantuan food

market and restaurant complex

established in 2007 in the out-of-the-way Lingotto

district. He shrugged.

“Maybe I visit someday.” And then he was off,

saying he was meeting friends at

a trattoria whose name he neglected to share with

us.

I must admit

that I, too, had

little knowledge of Turin, having only paid brief

visits to the city in the past

while attending a food conference or simply

passing through to tour the beauty

of the Piedmontese countryside and wine country,

where some of the region’s

most noted restaurants, like Combal.Zero in

Rivoli, Locanda del Pilone in Alba

and Delle Antiche Contrade in Cuneo, are located. My

earlier visits had, however, disabused me

of any thought that Turin was a drab,

self-absorbed northern industrial

city. It

is worth noting that director

Michelangelo Antonioni used Milan in “La Notte”

(1961), Rome in “L’Eclisse”

(1962) and Ravenna in “Il Deserto Rosso” (1964)—not Turin—to depict the deadening

effect of industrialization on

the soul of modern Italy.

On my last,

recent extended visit,

I found the heart of the city among the most

beautiful in Europe, justly famous

for its long, graceful series of arcades, the

grandeur of its vast piazzas, and

its stately and highly efficient grid pattern.

The Po River flows as majestically through

Turin as the Arno does

through Florence and the Tiber through Rome.

Fiat has, of course, dominated

and

buoyed Turin’s fortunes since 1899 (it still

produces 37 percent of Italy’s

GNP), but the Turinesi are quick to remind people

that their city was in fact

the first capital of an Italy unified in 1861

under Victor Emmanuel II, whose

Royal Palace (below), set in the huge

square entered from the broad Via Roma, is a

spectacular example of a  baroque

opulence intended to reflect the proud

independence of Piedmont, which only 50 years

earlier had been annexed by

Napoleon Bonaparte.

Upon invading Italy

in 1800, the young Corsican general faced 20,000

Piedmontese and 11,500

Austrians, but his tactical genius divided his

enemies and, in embarrassment,

King Victor Amadeus II ceded Piedmont to the

Corsican, who immediately

demolished Turin’s city gates and bastions and

renamed the Royal Palace as the

Imperial Palace—a decree that horrified and

humiliated the Turinesi. Napoleon’s

defeat at Waterloo in 1815 freed

Piedmont, whose power increased in the decades

leading up to 1861, when it

became the capital of the new Italy.

baroque

opulence intended to reflect the proud

independence of Piedmont, which only 50 years

earlier had been annexed by

Napoleon Bonaparte.

Upon invading Italy

in 1800, the young Corsican general faced 20,000

Piedmontese and 11,500

Austrians, but his tactical genius divided his

enemies and, in embarrassment,

King Victor Amadeus II ceded Piedmont to the

Corsican, who immediately

demolished Turin’s city gates and bastions and

renamed the Royal Palace as the

Imperial Palace—a decree that horrified and

humiliated the Turinesi. Napoleon’s

defeat at Waterloo in 1815 freed

Piedmont, whose power increased in the decades

leading up to 1861, when it

became the capital of the new Italy.

As an

imperial city, Turin’s

artistic treasures are exceptionally fine, all in

baroque wrappings. Although

there is no museum the equivalent of Florence’s

Uffizi or the Brera in Milan, the

Royal Palace itself—once residence of the powerful

Savoy dynasty, taken over by

the Italian government in 1946—is crammed with

notable works.

My wife and I were amazed at room after

room

of imperial salons, including

Queen Maria Theresa’s quarters, in every color of

marble, each with trompe l’oeuil painted ceilings,

and we were particularly

impressed with the palace’s collections of

exquisite tapestries and Chinese

porcelain.

including

Queen Maria Theresa’s quarters, in every color of

marble, each with trompe l’oeuil painted ceilings,

and we were particularly

impressed with the palace’s collections of

exquisite tapestries and Chinese

porcelain.

We toured

the city’s Egyptian

Museum at the Academy of Science (right),

considered one of the finest of its kind in

the world, on top of which sits the admirable Sabauda

Gallery (below), with works by

Bronzino, Veronese, Jan Van Eyck and Van Dyck. And

to gain a sense of the

unique way that Piedmontese royalty could actually

welcome the red-shirted

rebels of Garibaldi’s army, the  Museum

of the Risorgimento in the Palazzo

Carignano, where the first parliament of 1861 met,

depicts the region’s history

from the 19th century through Unification, and on

through two world wars.

Museum

of the Risorgimento in the Palazzo

Carignano, where the first parliament of 1861 met,

depicts the region’s history

from the 19th century through Unification, and on

through two world wars.

The

splendid Duomo of St. John the

Baptist, still home to the now wholly discredited

Shroud of Turin, is the

city’s only true example of pre-baroque

Renaissance architecture. And, as

everywhere else in Italy, there seems a church or

chapel on every block.

Uniquely

Turin, however, is its

National Museum of Cinema (below),

set inside a landmark 500-foot tower originally

designed as a synagogue in 1863 by Alessandro

Antonelli. We

wound from hall to hall and room to room

over five floors, flanked by flickering images of

early shadow cartoons and the

first primitive, silent efforts of Thomas Edison;

within the play of

chiaroscuro and expressionist lighting that evoked

“The Cabinet of Dr.

Caligari,” there are mini-theaters and long

corridors lined with huge movie

posters from every era. There is

also a

futuristic café-restaurant on the ground floor

whose starkness, color and light

could be a setting for a bar in “Star Wars” or

“Bladerunner.”

But if you ask a Turinese where his

city’s true artistic achievements lie, he might

well say they are in those

beautiful arched walkways that line miles of

streets and plazas throughout the

city center.

Of even height, woven

throughout the city so as to connect with one

another, the arcades were built

over the course of two centuries, principally as

shelter from Piedmontese

winters but also as showcases of banks and

boutiques, antique pharmacies and

food shops, and, more than anything else, cafés

and candy emporiums.

Look above their doorways and you see

stencils and carvings from the 18th and 19th

centuries. Their

façades are done in black marble, or

richly varnished mahogany, usually in the baroque

style but also in more

“modern” styles of Art Nouveau or Art Déco, and

they act very much like picture

frames for paintings.

One

of the most famous is Baratti & Milano

(1875; below), which bears the imperial

crest given it by the Vittorio II. The

King and Garibaldi toasted the Reunification at

Caffé Mulussano, later

relocated in 1907 and done in the sleek art deco

style of that period.

Litterateurs have long made Caffé Fiorio (1873)

their second home, and in his

day Fiat founder Gianni Agnelli passed his few

idle hours at Caffé Piatti

(1875). And while each has its secrets of coffee

making, it is likely that the

locally produced Lavazza coffee is the starting

point for the artfulness. While

café culture vitalized every large city

in Italy during the 19th century, none but Turin

brought it to an art form in

and of itself, where the cafes were extravagant

testimony to the luxurious

pleasures of taking time to sit, drink and talk. Indeed, it is the arcades that allow for

such

an extravagance of cafes barely imitated in

Venice’s Piazza San Marco.

Indeed, it is the arcades that allow for

such

an extravagance of cafes barely imitated in

Venice’s Piazza San Marco.

Through the spotless windows we saw

countless displays of the most

beautifully crafted chocolates, marzipan, and

sugared fritters in pastel

colors, pink paper, gold foil, arrayed in painted

tin boxes or set on lace

doilies. The

soft lighting inside is

never harsh, never low, imparting a Christmas

ornament’s appeal to the

confections every day of the year.

And

then

there is the aroma of the chocolate itself, almost

always commingled with

coffee set on the zinc or marble counters, where

white-coated barristas

grind, pack, adjust, steam,

fizz, and present their handiwork in a

manifestation of Turin’s deeply ingrained

coffee culture, richer than anywhere else in

coffee-obsessed Italy. The thunder

of the shuddering coffee machine, the clink of the

cups and saucers hitting the

bar and the tinkle of the little spoons in the

saucer never lets up. The barristas

pour a glass of Asti spumante for some, a tipple

of vermouth—created in Turin

by Antonio Benedetto Carpano in 1786—or a dark,

bittersweet amaro digestive for

others. A waiter delivers a slice of sugar-dusted

cake, covered with satiny

dark chocolate, with a filling of the

chocolate-and-hazelnut cream gianduja

that is also an invention of

Turin.

There

are many stories as to how gianduja

got its name, sometime in the 19th century, when

chocolate and coffee shops had

become the rage throughout Europe. Turin

tradition has it that the name derives from “Giovanni della doja” or “Gion

d’la duja”

(“John with a pint of

wine in his hands”), a popular commedia dell arte

marionette created by

Gioacchino Bellone di Raccongi first exhibited in

the city as of 1808.

Others contend it was named after di Oja, a

hamlet near Bellone’s hometown, and that the name

is really Giovanni di Oja.

Whatever

the origin of its name, gianduja

made

a tremendous contribution to European chocolate

candy as we know it, and in

Turin, hazelnuts seem inseparable from chocolate

in any form.

Indeed, Turin is chocolate mad, and yet

another of its finest sweet ideas was bicerin,

a small rounded glass with a metal handle (from

which it gets its name) of hot

espresso, chocolate, and milk. Various

aficionados debate the origins of this totemic

Turinese concoction, though the

most widely accepted was that it was first made at

Caffè al Bicerin, which

opened on the Piazza della Consolata in 1763.

(Incidentally, the church across the piazza

has one of the most extraordinary

interiors in Turin.)

Whatever

the origin of its name, gianduja

made

a tremendous contribution to European chocolate

candy as we know it, and in

Turin, hazelnuts seem inseparable from chocolate

in any form.

Indeed, Turin is chocolate mad, and yet

another of its finest sweet ideas was bicerin,

a small rounded glass with a metal handle (from

which it gets its name) of hot

espresso, chocolate, and milk. Various

aficionados debate the origins of this totemic

Turinese concoction, though the

most widely accepted was that it was first made at

Caffè al Bicerin, which

opened on the Piazza della Consolata in 1763.

(Incidentally, the church across the piazza

has one of the most extraordinary

interiors in Turin.)

Like

the equally famous though not nearly so old Caffé

Sant’ Eustachio in Rome,

Caffè al Bicerin (above) is a

revered monument to coffee and chocolate, a dim,

fifteen-by-twenty-five-foot room with tiny marble

tables, candles that seem

votive, antique mirrors, dark red banquettes, wall

sconces, and old wooden

chairs. The cramped counter holds jars of bon bons

and chocolates, and the old

Faema coffee machine rumbles and roars like a Fiat assembly

line when the glasses of thick, semi-sweet

bicerins are made.

My wife and I entered

feeling like acolytes, privileged to sit at a tiny

table among an array of

Turinesi, many of them old men and women for whom

a morning bicerin is like

receiving Holy Communion, as a restorative against

the Piedmontese fog and

drizzle.

❖❖❖

By John Mariani

LOVE AND PIZZA

Since, for the time being, I am unable to write about or review New York City restaurants, I have decided instead to print a serialized version of my (unpublished) novel Love and Pizza, which takes place in New York and Italy and involves a young, beautiful Bronx woman named Nicola Santini from an Italian family impassioned about food. As the story goes on, Nicola, who is a student at Columbia University, struggles to maintain her roots while seeing a future that could lead her far from them—a future that involves a career and a love affair that would change her life forever. So, while New York’s restaurants remain closed, I will run a chapter of the Love and Pizza each week until the crisis is over. Afterwards I shall be offering the entire book digitally. I hope you like the idea and even more that you will love Nicola, her family and her friends. I’d love to know what you think. Contact me at loveandpizza123@gmail.com

—John Mariani

To read previous chapters go to archive (beginning with March 29, 2020, issue.

LOVE AND PIZZA

Cover Art By Galina Dargery

The

next morning Marco arrived on time and the

couple took a taxi to the dock in

time to catch t he

9:10 fast ferry to Naples, arriving at ten

o’clock.

Marco found a taxi driver he knew and

they

set off, in full view of the Royal Palace of

Naples and into the maze of

streets that on Sunday morning were quiet and

easy to navigate. Past

the Archaeological Museum they turned

onto Via Santa Teresa then the Via Miano and

arrived at the Museo di

Capodimonte (below), located in a 17th

century Spanish Bourbon

palace.

Bourbon

palace.

When

French troops entered the city in 1806 much of

the artwork not already removed

to safety was looted, and upon the troops

leaving in 1815, King Ferdinand

restored and restocked the palace, which only

became a full-fledged national

museum as of 1950.

Once

inside, Marco, holding Nicola’s hand, walked

swiftly through rooms that

retained the architectural grandeur of its time

as a royal residence, then

slowed down as they entered the Galleria

Nazionale, where they would find an

extensive collection of the Neapolitan School

artwork as well as paintings by

Raphael, Titian, Masaccio, El Greco and

Caravaggio.

Marco

explained

that Caravaggio was born in Milan and his use of

dramatic light and

dark—chiaroscuro—had enormous influence on

Neapolitan artists during his short

time in Naples.

Marco

explained

that Caravaggio was born in Milan and his use of

dramatic light and

dark—chiaroscuro—had enormous influence on

Neapolitan artists during his short

time in Naples.

“They

were called the caravaggisti,”

said

Marco, who pointed out their similarities of

style in paintings whose subjects

were always more theatrically posed than the

sublime renderings of the same

subjects by northern artists. “Unfortunately,

many

of them died during a plague epidemic in 1756,

and the movement quickly

dissipated. Ars longa,

vita brevis.”

Nicola,

remembering her Latin, repeated in English, “Art

is long, life is short.”

Nicola

was in awe of so many masterpieces she was

unaware existed by artists she’d

never heard of.

She could, of course,

see the influence of other artists from other

regions, but that was true

everywhere in Europe during the Renaissance,

when travel to Italy was requisite

for any serious young painter.

Marco

moved his fingers in front of various paintings,

telling Nicola that the

Neapolitan painters could never hide their

deep-seated sense of tragedy, which,

of course, was rife in religious art.

“They

reveled in what was horrifying, always conscious

of death and decay, but they

suffused it all with a bravura of light and

color that forced the viewer to

respond both emotionally and spiritually.

They painted a skull with the same skill

they brought to a portrait, and

the more dreadful the martyrdom, the more

sublime they made the saint look.”

Nicola

nodded at what Marco told her and said, “You’d

make a terrific art teacher.”

“Please,”

Marco laughed.

“I make little enough

money as it is.”

After

perusing several more galleries, Marco said, “We

have only scratched the

surface. You

must come back to Napoli

and stay for a while.”

Nicola

assented, saying, “I must admit you're right

about the Neapolitan School. It’s

really been neglected  by the

professors.”

by the

professors.”

“But

now,” Marco said, clapping his hands, “I am

starving. Do you want to have the

best pizza in Napoli?”

Nicola

smiled broadly and said, “I couldn’t imagine

anything I’d rather have right

now. I

never had time to get breakfast.”

“Okay,

we go then.

I take you to my favorite

place, in Spaccanapoli, the old town. It’s very

close by.”

Nicola

had heard the name Spaccanapoli—“split

Naples”—for it cut like a black ribbon

in a straight line through the most ancient part

of the city center, and though

it is lined with churches and urban palaces, its

reputation as being dirty,

cramped and dangerous was well known among

tourists.

It

was now past one o’clock, and the city was only

beginning to emerge from the

revelries of Saturday night and the requisites

of attending Mass, which would

be followed by family dinner. The

wash

that usually hung on clotheslines like wet

banners had mostly been taken in,

and, except for the narrowness of the street, it

all reminded Nicola of where

she was born and grew up.

Nicola,

intentionally, slipped into the little true

Neapolitan dialect she knew,

saying, “Nun e’ assai diverse a comme addo

stong e casa a New York. This is

not very different from where I live in New

York.”

Marco’s

eyes widened and he said, “Ah, Nicola, so you

know Neapolitan! That’s wonderful.

How about we speak it over lunch?”

Nicola

had bitten off more than she could

linguistically chew and replied, “It won’t

be easy for me, but I’ll try.”

“Brava!

Okay, I promise I won't correct

you. Ah, here we are. Pizzeria

Scugnizzo.”

To

say the pizzeria was a hole in the wall was high

praise, for a door fit for

only one person at a time to pass through led to

a room with just four tables,

a board for a bar, and a pizza oven in the rear,

tended by a very large man who

rarely turned towards the guests.

“That’s

Angelo,” whispered Marco in English.

“People say he was ordained by God to

make pizzas and has no other

skills whatsoever.”

Another

man, who didn't need to walk a step to greet the

couple, welcomed Marco like an

old friend, then commented on Nicola being so

beautiful. “Si,” said Marco, “Essa e’

bella e assai intelligente. E’

n’

scolaro d’artista! E tene o’ sangue Napulitane

dinte ‘e vene. She is very

beautiful and very intelligent. A scholar of

art! And she has Neapolitan blood

in her veins!”

This

revelation caused the man to clap his hands

together and say, “Tenimme ‘o

mazzo scassato oggi. Comme te

chiamme, Nenne’? Then

we are all

lucky today. What is your name, Signorina?”

This

revelation caused the man to clap his hands

together and say, “Tenimme ‘o

mazzo scassato oggi. Comme te

chiamme, Nenne’? Then

we are all

lucky today. What is your name, Signorina?”

“Nicola

Santini.”

“Santini!

A faccia mia, allo simme

pariente.

Ce stanne certi Santini tra i

pariente miei. O meglie zie, me pense.

Ah, maybe we are related. There

are some Santinis somewhere among my ancestors.

A great uncle, I think.”

Nicola

was having a hard time understanding the

dialect, but she heard the same sounds

she’d grown up with and felt far more at home

than she ever did in Milan.

A

pizza alla

margherita was ordered,

two glass tumblers were placed on the table

along with a bottle of red wine,

without a cork.

Nicola was breathing in

the smoky aroma of the place, watching Angelo

make his ten millionth pizza as

if it were a special event, and then, four

minutes later, two steaming pies

with their melted mozzarella, crushed tomatoes

and basil set on a bubbling,

charred crust came to their table.

Raising

his eyes to heaven, Marco announced, “Stu

mumento e’ sacro! Nicola Santini sta pe’ da ‘o

primme muorzeche a pizza ‘e

Angelo!” This is a sacred moment! Nicola

Santini is about to have her first

taste of Angelo’s pizza!”

Nicola

smiled, cut off a piece from the pie, blew on it

and placed it on her

tongue. Suddenly

her mind ran riot with

the memories of all the pizzas she’d ever

eaten—in New York, in Milan—and how

this pizza came as close to the one made at Alla

Teresa as it could possibly

be. It

was different from Paper Moon’s,

not as thin, not as crisp, with a flaccid middle

that Joe Bastone would

applaud. The

melding of the ingredients,

the taste of the yeast, and the aroma of the

barely cooked basil all coalesced

into a moment of revelation to Nicola, who now

felt herself linked forever and

more intimately than ever before to these people

who surrounded her.

The

pizza was the savory link, but the sense that

she knew how good this pizza was,

just as she knew Italian art, meant

that all that had happened to her in the past

year seemed part of a destiny

that led her to this tiny room in Spaccanapoli.

Nicola

turned to Marco, gave him a huge kiss on the

cheek, and said, “I am deliriously

happy at this moment, Marco!”

The

waiter,

even Angelo, turned around and applauded. More

wine was poured, more pizza was

consumed, and life was very good for everyone

that day.

By John Mariani

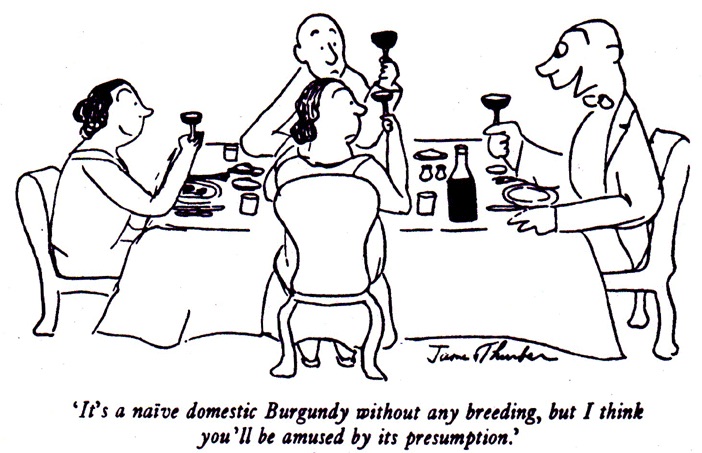

Such winespeak can get pretty

pretentious

if not downright silly. Yet

the increased interest in wine among Americans has

made the once-unimaginable

idea of a wine tasting a capital reason for a good

party. I

say unimaginable because such a social

event once seemed to be a connoisseur’s game of

one upmanship.

Today, though, gathering friends to taste

and

discuss wines has become one of the most convivial

ways to get together and far

less exclusionary and competitive than a bridge

club or poker night. So, when the pandemic lifts

in 2021, a lot of people will be dying to get

together and taste wines in such a convivial

exercise.

Such winespeak can get pretty

pretentious

if not downright silly. Yet

the increased interest in wine among Americans has

made the once-unimaginable

idea of a wine tasting a capital reason for a good

party. I

say unimaginable because such a social

event once seemed to be a connoisseur’s game of

one upmanship.

Today, though, gathering friends to taste

and

discuss wines has become one of the most convivial

ways to get together and far

less exclusionary and competitive than a bridge

club or poker night. So, when the pandemic lifts

in 2021, a lot of people will be dying to get

together and taste wines in such a convivial

exercise.

The idea of simply assembling a bunch of wines to taste without any focus can, however, become tiresome. On the other hand, bringing together people who may know little or nothing about wine and people who think they know everything about wine is very much like inviting people from Madagascar to a Super Bowl party. It gets. . . awkward.

So, here are a few guidelines to holding a wine tasting for people who have a general knowledge and interest in wine rather than those who consider discussion of Ph levels and vine trellising fit conversation at a party.

The first rule of thumb is not to serve too many wines—six is an ideal amount. Fewer is a sipping, not a tasting. Ten becomes a chore.

Next, you should decide if you’ve going to taste the wines blind, that is, without revealing their names, not in an

effort to fool or

embarrass anyone but to

judge their character according to people’s likes

rather than mere familiarity

with a famous name.

You might feature

wines from a particular region, like Tuscany or

New Zealand, Napa Valley or

Sicily. Or by varietal grape, like cabernet

sauvignon, grenache or

chardonnay. “A

vertical tasting is when

you taste the exact same wine from the same

producer but in different

vintages,” says Gabrielle Waxman, former wine

director for Galatoire’s

restaurant in New Orleans. “A horizontal tasting

is when you taste wines from

the same vintage or the same grape varietal but

from different producers.”

effort to fool or

embarrass anyone but to

judge their character according to people’s likes

rather than mere familiarity

with a famous name.

You might feature

wines from a particular region, like Tuscany or

New Zealand, Napa Valley or

Sicily. Or by varietal grape, like cabernet

sauvignon, grenache or

chardonnay. “A

vertical tasting is when

you taste the exact same wine from the same

producer but in different

vintages,” says Gabrielle Waxman, former wine

director for Galatoire’s

restaurant in New Orleans. “A horizontal tasting

is when you taste wines from

the same vintage or the same grape varietal but

from different producers.”If so, you should cover the bottles with a paper bag to hide the labels. The bag should also disguise the shape of the bottle because some varietals, like pinot noir and riesling, are always sold in specifically shaped bottles. Then, number the bags and reveal the labels only after all are tasted.

As to

glassware, connoisseurs

usually stick with a single shape, even though

restaurants may serve different

varietals in different shapes, like Alsatian wines

in green-stemmed glassware.

As to

glassware, connoisseurs

usually stick with a single shape, even though

restaurants may serve different

varietals in different shapes, like Alsatian wines

in green-stemmed glassware.The best type to use is a thin wineglass in which a four-ounce pour fills about half the glass. This allows for swirling and sniffing the aroma of the wine, itself a point of discussion.

If you are tasting the wines before dinner, have plain water and crackers or bread available to restore your palate wine after tasting the wine. Salted butter on the cracker is also an excellent way to intensify the flavors of the wine, because salt

and fat intensify

flavors.

and fat intensify

flavors.If you are serving the wines with dinner, keep the food simple so that the wine remains the focus. Simply grilled red meat goes well with big reds, while cheeses or seafood without a spicy sauce bring out the best in whites, and vice-versa.

You might also consider a Champagne tasting, since there are so many labels, styles and price levels available in the U.S. now. You go by colors, from yellow to golden to rosé, and some have floral bouquets, others are more robust and toasty. You may also try them by grape varieties: blanc de blancs are made with all white chardonnay grapes, while blanc de noirs are made from red pinot noir. There are also vintage and non-vintage, and premium prestiges cuvées.

As host, you should try to stir discussion, without any momentous pronouncements. To set the atmosphere, it’s a good idea to begin with a memorable quotation from a great person, like Thomas Jefferson, who said, “No nation is drunken where wine is cheap” or Lord Byron, who wrote, “Let us have wine and women, mirth and laughter,/ Sermons and soda-water the day after.”

The travel site VISIT CROATIA: Tasteful Croatian Journeys is featuring Salzburg and Munich, Germany, and Prague, Czech Republic but none in Croatia.

MAN OF THE YEAR:

Mario Lopez as Col. Sanders of KFC.

❖❖❖

Sponsored by

Any of John Mariani's books below may be ordered from amazon.com.

The Hound in Heaven

(21st Century Lion Books) is a novella, and

for anyone who loves dogs, Christmas, romance,

inspiration, even the supernatural, I hope you'll find

this to be a treasured favorite. The story

concerns how, after a New England teacher, his wife and

their two daughters adopt a stray puppy found in their

barn in northern Maine, their lives seem full of promise.

But when tragedy strikes, their wonderful dog Lazarus and

the spirit of Christmas are the only things that may bring

his master back from the edge of despair.

The Hound in Heaven

(21st Century Lion Books) is a novella, and

for anyone who loves dogs, Christmas, romance,

inspiration, even the supernatural, I hope you'll find

this to be a treasured favorite. The story

concerns how, after a New England teacher, his wife and

their two daughters adopt a stray puppy found in their

barn in northern Maine, their lives seem full of promise.

But when tragedy strikes, their wonderful dog Lazarus and

the spirit of Christmas are the only things that may bring

his master back from the edge of despair. WATCH THE VIDEO!

“What a huge surprise turn this story took! I was completely stunned! I truly enjoyed this book and its message.” – Actress Ali MacGraw

“He had me at Page One. The amount of heart, human insight, soul searching, and deft literary strength that John Mariani pours into this airtight novella is vertigo-inducing. Perhaps ‘wow’ would be the best comment.” – James Dalessandro, author of Bohemian Heart and 1906.

“John Mariani’s Hound in Heaven starts with a well-painted portrayal of an American family, along with the requisite dog. A surprise event flips the action of the novel and captures us for a voyage leading to a hopeful and heart-warming message. A page turning, one sitting read, it’s the perfect antidote for the winter and promotion of holiday celebration.” – Ann Pearlman, author of The Christmas Cookie Club and A Gift for my Sister.

“John Mariani’s concise, achingly beautiful novella pulls a literary rabbit out of a hat – a mash-up of the cosmic and the intimate, the tragic and the heart-warming – a Christmas tale for all ages, and all faiths. Read it to your children, read it to yourself… but read it. Early and often. Highly recommended.” – Jay Bonansinga, New York Times bestselling author of Pinkerton’s War, The Sinking of The Eastland, and The Walking Dead: The Road To Woodbury.

“Amazing things happen when you open your heart to an animal. The Hound in Heaven delivers a powerful story of healing that is forged in the spiritual relationship between a man and his best friend. The book brings a message of hope that can enrich our images of family, love, and loss.” – Dr. Barbara Royal, author of The Royal Treatment.

|

The Encyclopedia of American Food and Drink by John F. Mariani (Bloomsbury USA, $35) Modesty forbids me to praise my own new book, but let me proudly say that it is an extensive revision of the 4th edition that appeared more than a decade ago, before locavores, molecular cuisine, modernist cuisine, the Food Network and so much more, now included. Word origins have been completely updated, as have per capita consumption and production stats. Most important, for the first time since publication in the 1980s, the book includes more than 100 biographies of Americans who have changed the way we cook, eat and drink -- from Fannie Farmer and Julia Child to Robert Mondavi and Thomas Keller. "This book is amazing! It has entries for everything from `abalone' to `zwieback,' plus more than 500 recipes for classic American dishes and drinks."--Devra First, The Boston Globe. "Much needed in any kitchen library."--Bon Appetit. |

"Eating Italian will never be the same after reading John Mariani's entertaining and savory gastronomical history of the cuisine of Italy and how it won over appetites worldwide. . . . This book is such a tasteful narrative that it will literally make you hungry for Italian food and arouse your appetite for gastronomical history."--Don Oldenburg, USA Today. "Italian

restaurants--some good, some glitzy--far

outnumber their French rivals. Many of

these establishments are zestfully described

in How Italian Food Conquered the World, an

entertaining and fact-filled chronicle by

food-and-wine correspondent John F.

Mariani."--Aram Bakshian Jr., Wall Street

Journal.

"Equal parts

history, sociology, gastronomy, and just

plain fun, How Italian Food Conquered the

World tells the captivating and delicious

story of the (let's face it) everybody's

favorite cuisine with clarity, verve and

more than one surprise."--Colman Andrews,

editorial director of The Daily

Meal.com. "A fantastic and fascinating

read, covering everything from the influence

of Venice's spice trade to the impact of

Italian immigrants in America and the

evolution of alta cucina. This book will

serve as a terrific resource to anyone

interested in the real story of Italian

food."--Mary Ann Esposito, host of PBS-TV's

Ciao

Italia. "John Mariani has written the

definitive history of how Italians won their

way into our hearts, minds, and

stomachs. It's a story of pleasure over

pomp and taste over technique."--Danny Meyer,

owner of NYC restaurants Union Square

Cafe, The Modern, and Maialino.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Everett Potter's Travel Report:

Everett Potter's Travel Report:

Eating Las

Vegas JOHN CURTAS has been covering

the Las Vegas food and restaurant scene

since 1995. He is the co-author of EATING LAS

VEGAS – The 50 Essential Restaurants (as

well as the author of the Eating Las

Vegas web site: www.eatinglasvegas.

He can also be seen every Friday morning as

the “resident foodie” for Wake Up With the

Wagners on KSNV TV (NBC) Channel 3 in

Las Vegas.

Eating Las

Vegas JOHN CURTAS has been covering

the Las Vegas food and restaurant scene

since 1995. He is the co-author of EATING LAS

VEGAS – The 50 Essential Restaurants (as

well as the author of the Eating Las

Vegas web site: www.eatinglasvegas.

He can also be seen every Friday morning as

the “resident foodie” for Wake Up With the

Wagners on KSNV TV (NBC) Channel 3 in

Las Vegas.

MARIANI'S VIRTUAL GOURMET

NEWSLETTER is published weekly. Publisher: John Mariani. Editor: Walter Bagley. Contributing Writers: Christopher Mariani,

Robert Mariani, Misha Mariani, John A. Curtas, Gerry Dawes, Geoff Kalish,

and Brian Freedman. Contributing

Photographer: Galina Dargery. Technical

Advisor: Gerry

McLoughlin.

If you wish to subscribe to this

newsletter, please click here: http://www.johnmariani.com/subscribe/index.html

© copyright John Mariani 2021