IN THIS ISSUE

TEN THINGS THAT NEVER GET

OLD ABOUT A BISTRO

By John Mariani

NEW YORK CORNER

LOVE AND PIZZA

CHAPTER 44

By John Mariani

NOTES FROM THE WINE CELLAR

TENUTA DI ARCENO Q&A

By John Mariani

❖❖❖

On the next video episode of Celebrating Act 2 on January 27, I will be speaking with hosts John Coleman and Art Kirsch about the topic of "Do Corporate Restaurant Groups Offer Better Quality?"

OLD ABOUT A BISTRO

“Fashion,”

said French couturier Coco Chanel (left),

“is made to go out of style,” and as I read

about how insects are the hot new menu item or

about a restaurant in Brooklyn where dinner is

held in total silence, I wag my head and

consider that, like pizzerias in Naples, pubs in

Dublin, and dumpling houses in Canton, the

traditional French bistro has never been out of

style, because, like work boots, they were never

deliberately stylish in the first place.

“Fashion,”

said French couturier Coco Chanel (left),

“is made to go out of style,” and as I read

about how insects are the hot new menu item or

about a restaurant in Brooklyn where dinner is

held in total silence, I wag my head and

consider that, like pizzerias in Naples, pubs in

Dublin, and dumpling houses in Canton, the

traditional French bistro has never been out of

style, because, like work boots, they were never

deliberately stylish in the first place.

I owe a great deal to the French bistro,

where I ate my first meal in Paris, alone in the

Gare du Nord at the age of nineteen. My high

school French allowed me to decipher little on a

menu listing suprêmes de volaille,

potage  Saint-Germain,

quenelles de brochet, and tripes à la

mode Caen, but I spotted blanquette de

veau (right), which sounded like a

homey veal dish.

Saint-Germain,

quenelles de brochet, and tripes à la

mode Caen, but I spotted blanquette de

veau (right), which sounded like a

homey veal dish.

When the pudgy,

black-jacketed, white-aproned waiter brought a

large ceramic casserole to my table and lifted the

lid, the steamy aroma of cream, veal and green

beans hit me with the force of tear gas, but the

tears were of joy, not pain. The

ingredients of the dish melded in such exquisitely

simple flavors that I realized I had never had

food this good.

Accompanied

by a paper-wrapped baguette and a carafe of

Beaujolais, I experienced a true epiphany that,

without my knowing it then, would someday set me

off on a career writing about good food and wine.

Accompanied

by a paper-wrapped baguette and a carafe of

Beaujolais, I experienced a true epiphany that,

without my knowing it then, would someday set me

off on a career writing about good food and wine.

The pleasures of a French bistro—however

twisted the meaning of the word has become to

describe just about any small restaurant of any

stripe—have never waned, even if the term covers a

lot of non-bistro restaurants and the food has

nudged somewhat towards contemporary taste And

here’s why they’ll never get old.

1. Bistros

are

neighborhood restaurants, set on a corner or in a

cul-de-sac, not on grand boulevards or in malls. They are

family places—often mom-and-pop owned—where other

families dine on Sundays or special occasions, and

where the older aunts and uncles are assured they

will have their favorite dish made as it was years

and years ago.

2. Bistros

are built for sheer comfort: Lace curtains hang in

the windows, the floors are of colored tiles,

copper pots hang on the walls, the tablecloths are

stiff, the chairs sturdy, the banquettes always

red or brown leather and the old mirrors are

slightly tilted to give everyone a better look at

everyone else.

There are newspapers for the solo diner to

read and catch up.

Always lively but never raucous, the

ambiance of a bistro is the epitome of bonhomie. Everyone

is happy for a little while.

3. Before

you even read the menu, there will be good crusty

bread and abundant butter on the table, along with

a pot of fresh flowers, or one single flower. A votive

candle will be lighted at night. You may be

offered a complimentary apéritif—a little white

Port perhaps, a finger of vermouth.

4. Bistros

are

fast paced, for, while there’s no reason you can’t

spend hours there over coffee and cognac, the

service is always brisk, the food starts coming

out moments after you order, the wine cork is

popped and the wine poured as you break off your

first morsel of bread; the check is delivered

within seconds of your asking for it, and the

staff’s thank-you’s and au revoirs are proffered

without feigned flourish.

4. Bistros

are

fast paced, for, while there’s no reason you can’t

spend hours there over coffee and cognac, the

service is always brisk, the food starts coming

out moments after you order, the wine cork is

popped and the wine poured as you break off your

first morsel of bread; the check is delivered

within seconds of your asking for it, and the

staff’s thank-you’s and au revoirs are proffered

without feigned flourish.

with

crème fraîche.

with

crème fraîche.

7. Bistros serve

plenty of offal, from calf’s liver (below)

to kidneys, brains to tongue, head cheese to tail,

and the fish is delivered to the back door fresh

from Rungis market, where it was unloaded in the

middle of the night with seafood from the

Mediterranean and North Atlantic.

8. Bistro wine

lists are both dependable and modestly priced,

with a few rare bottles the owner keeps for

special guests. There will be plenty of vins de

Pays, regional wines from  the Loire Valley and Provence, and

some will be offered by the carafe.

the Loire Valley and Provence, and

some will be offered by the carafe.

9.

Since bistros are neighborhood restaurants, most

do not dare charge exorbitantly, except Paris

tourist traps like L’Amis Louis, where the roast

chicken for two runs $130 and everyone eating

there is either American or Chinese.

❖❖❖

LOVE AND PIZZA

Since, for the time being, I am unable to write about or review New York City restaurants, I have decided instead to print a serialized version of my (unpublished) novel Love and Pizza, which takes place in New York and Italy and involves a young, beautiful Bronx woman named Nicola Santini from an Italian family impassioned about food. As the story goes on, Nicola, who is a student at Columbia University, struggles to maintain her roots while seeing a future that could lead her far from them—a future that involves a career and a love affair that would change her life forever. So, while New York’s restaurants remain closed, I will run a chapter of the Love and Pizza each week until the crisis is over. Afterwards I shall be offering the entire book digitally. I hope you like the idea and even more that you will love Nicola, her family and her friends. I’d love to know what you think. Contact me at loveandpizza123@gmail.com

—John Mariani

To read previous chapters go to archive (beginning with March 29, 2020, issue.

LOVE AND PIZZA

Cover Art By Galina Dargery

New York’s

weather both fascinated and astounded Marco di

Noè. On January 15 the temperature dropped to

eight degrees—the coldest of the year. For a

Neapolitan like Marco the cutting frigidity of

the air was startling, and more than once he

asked himself how people in New York could live

this way. Then three days later the temperature

hit 63; starting

on the 28th snow fell for four days in a row.

His job and his painting were going well,

though the former demanded little that month

because the Harrisons had gone off to Colorado to

ski. So

Marco was able to spend time painting and seeing

Nicola, who did indeed invite him up to Belmont. On one

of the warmer days, he took the train from Grand

Central up to Fordham, where Nicola met him, then

they walked along Fordham Road, past the

university, then turned onto Arthur Avenue.

Within

two blocks Marco began commenting on similarities

to Naples. The

buildings were lower and the streets broader than

Spaccanapoli’s, and the streets had all English

names, left over from the original Anglo and Dutch

settlers of the Bronx. But when

he began seeing all the Italian names on store

signs, he had a sense of being far closer to home

than he did on Fifth Avenue.

Within

two blocks Marco began commenting on similarities

to Naples. The

buildings were lower and the streets broader than

Spaccanapoli’s, and the streets had all English

names, left over from the original Anglo and Dutch

settlers of the Bronx. But when

he began seeing all the Italian names on store

signs, he had a sense of being far closer to home

than he did on Fifth Avenue.

He was not surprised that some of the

merchants put out their refuse onto the curb,

especially since clearing away the snow had been

hampered by cars parked on both sides of the

street. He

saw no Fiats; instead, there were mostly big

American cars—Buicks, Oldsmobiles, Mercurys,

Lincolns, Cadillacs, along with smaller Japanese

models, Toyotas, Nissans, Subarus.

The first thing Nicola did was to bring him

to her family’s apartment.

“See,” she said, putting on false airs, “I live

in a duplex too!”

It was the middle of the day, so only her

mother was home, and Anna welcomed the Neapolitan

warmly in dialect—hers was much better than

Nicola’s—and apologized for not making him lunch.

“Nicola said she wanted you to see our

son’s restaurant, Alla Teresa, so I was forbidden

to cook this time.

But you come back and we’ll have a big

family dinner. You look a little skinny.”

“He’s a starving artist,” said Nicola,

holding Marco’s arm.

“Okay,” said Anna, “we’ll fatten him up.”

With that, the couple left the house and

walked over to Alla Teresa, where

Tony’s first words to Marco were, “I hear you’re

the best cook in Italy.”

Marco said, “Ah, maybe just on Capri. It’s

very, very small.”

“Well, I hope you like how we cook here. It’s a

little different, Italian-American, but it’s good

food. So,

we start off with a pizza?”

Nicola was thrilled by the prospect of

showing off Alla Teresa’s pizza alla

margherita, and Tony, winking at his sister,

sat them right under the photo of her made up like

Claudia Cardinale, which Marco looked hard at.

“Nicolina, is that you?”

“That’s me. My first modeling job in

Milan.”

“You look almost as beautiful as Claudia

Cardinale as you do Nicola Santini,” he said,

framing her face with his fingers as if taking a

photo.

The pizza arrived and Marco eyed it

critically. “Hm, looks very good,” he said,

serving Nicola the first slice. “But

it’s so big!”

Nicola told him that in America everything

is big, including the pizzas. “You’re

supposed to share it.”

Marco took his first bite, then another,

shaking his head and saying, “Nicolina, c’e perfetto! The

crust is very good, a little soft in the middle

and with the burned bubbles. I love this

pizza!”

Tony

had joined the conversation. “So we make a pretty

good pizza here, Marco? Nicky

told me about the one she had in Naples.”

Tony

had joined the conversation. “So we make a pretty

good pizza here, Marco? Nicky

told me about the one she had in Naples.”

Marco began to clap his hand softly. “Tony,

I thought I would never say this—because I’ve had

some pizzas in New York in the past month—but

nothing like this. Bravissimo,

Tonino! Bravissimo!”

Tony took a little bow and said, “I hope

everything else lives up to the pizza. Lemme go

see how things are going back in the kitchen.”

While waiting, Marco looked over the menu,

reading dish after dish he’d never heard of and

looking very confused.

“Nicolina,” he said, “what are these

dishes? I’ve never heard of chicken parmigiana,

clams Posillipo, mussels Golf di Napoli, penne

alla vodka. Are

these Tony’s creations?”

Nicola explained that they were dishes that

the immigrants named when they opened restaurants

in New York.

“Most of them had never eaten at a

restaurant in, say, Naples, but they were good

cooks and so they adapted what they knew to

American ingredients and named them after their

hometowns.”

Marco was still puzzled and, when the first

dishes began to come out from the kitchen, he was

startled by the enormity of the portions. “Are

these for two people?” he asked.

Nicola laughed and said, “No, but that’s

another part of the story. The

immigrants found that food was pretty cheap here,

and since they never had enough to eat in the Old

Country, they took advantage of their good

fortune. Plus,

Americans have always been used to huge portions.”

Marco enjoyed the food—a cold octopus

salad, spaghetti with vongole

clams in their shells, and shrimp scampi.  This

last caused him to comment, “But these are not scampi;

they’re shrimp.”

This

last caused him to comment, “But these are not scampi;

they’re shrimp.”

Nicola

further explained that true scampi—prawns—were

rarely available in American fish markets, so they

used jumbo shrimp.

“I know it’s a silly name, but it’s come to

mean shrimp cooked in garlic and white wine.”

Tony also served the couple a sixteen-ounce

New York strip steak with garlicky sautéed

broccoli di rape. Marco pronounced the steak to be

the best beef he’d ever tasted.

With the meal they drank a good bottle of

Vino Nobile di Montepulciano. The

couple was too full for dessert, so they just had

espresso, which came with a lemon rind. Marco

held it up and said, “Why do they give you this?”

“I don’t really know,” said Nicola. “I

heard it’s because the coffee used to be very poor

quality, so the lemon cut the bitterness. At least

that’s the story.”

Marco found this very odd but shrugged and

said, “I have a lot to learn. You

know, I’ve been to a couple of so-called ‘Northern

Italian’ restaurants in New York but they also

have all these dishes I’ve never heard of. And why

do they all serve salmon, salmon, salmon? Italians

don't eat salmon.”

Sensing Marco was frustrated by what he’d

seen and tasted, Nicola was a bit anxious asking

him what he thought of Alla Teresa’s food. “Be

honest,” she said.

Marco finished his coffee and said, “It’s

good. The ingredients are good quality and the

food tastes fresh.

The shrimp maybe not so much.”

“All the shrimp you get in restaurants in

the U.S. are frozen.”

Marco looked shocked. “Frozen? My God, c’e

terribile! Why don’t they have fresh

shrimp?”

“Because it’s easier to grow shrimp and

freeze it than to ship it from down South because

it’s so perishable.”

“Then

they shouldn’t serve it at all,” said Marco

sternly. “Please, I hope you and Tony are not

offended. It

is just that where I come from they would shoot a

cook who used frozen seafood. But,

Nicolina, the food is good here. It just

lacks refinement, finezza. The chef

is not cooking from his heart.”

“Then

they shouldn’t serve it at all,” said Marco

sternly. “Please, I hope you and Tony are not

offended. It

is just that where I come from they would shoot a

cook who used frozen seafood. But,

Nicolina, the food is good here. It just

lacks refinement, finezza. The chef

is not cooking from his heart.”

“Believe me,” said Nicola. “I know. I’ve

tasted the way you cook and I know what you mean.

But, Marco, you cooked for, what, 40 people on

busy night? In

America, you have to cook for twice that many at

least just to make a little money.”

“Allora,

Nicolina, I won’t say anything more. I very

much enjoyed the meal. Now I

don’t eat for another three days!”

Nicola wished so much to go to bed with

Marco that evening, but it was out of the question

at her house and Marco completely understood.

“But next time I see you, you come to my

apartment and spend the night.”

Nicola

leaned in and kissed him sweetly. “I’m

sure I can arrange that without too much trouble

and without my father and brothers killing you

afterwards.”

© John

Mariani, 2020

❖❖❖

THE WINES OF TENUTA DI ARCENO

ARE

CHANGING OUTMODED VIEWS OF CHIANTI

By John Mariani

The

success

of the Chianti Classico appellation in

Tuscany has been accompanied by aggressive,

sometimes antagonistic, arguments about how

breaking long-established rules of what

grapes may go into Chianti Classico would

allow producers to make wines from 100%

Sangiovese, perhaps adding Cabernet

Sauvignon to the blend. The result was a fad

for so-called Super Tuscans—never an

official or sanctioned term—and led to the

establishment under Italian wine laws of the

I.G.T. appellation, which gave

such wines a nod as being “typical” of the

region.

Since then, producers within the larger

Chianti zone have sought to re-design its map

in order better to focus on regional terroirs,

a label term called “menzioni

aggiuntive” that recognizes the

biodiversity of the region. Leading this

movement has been Tenuta di Arceno, whose

history began with the Del

Taja family in 1504, followed by the

Piccolomini family of Siena in 1829. In

1994 Tenuta di Arceno was acquired by

American wine producers Jess Jackson and

Barbara Banke, one of the first estates the

Jackson Family purchased outside of

California.

I interviewed Arceno’s American-born

winemaker, Lawrence Cronin (left),

about the winery’s commitment to evolution in

the region.

How

did you come to be the winemaker at the

estate? Did you think it was a short-term

project?

How

did you come to be the winemaker at the

estate? Did you think it was a short-term

project?

I arrived to the estate from Anderson Valley in California with just two days notice. Originally, the position was for two months to set up the lab and put things in place for the harvest. It was June, 2002, and at the time my grandmother was still living in Sicily. I grew up spending summers there, so adapting to the culture in Tuscany was not a dramatic change for me. I had previously made wine in Sicily, and had international winemaking experience from harvests in New Zealand, Australia, and Chile. As summer quickly transitioned to fall, the founding winemaker, Pierre Seillan, asked if I would stay for harvest, and you can imagine how the rest of the story unfolds. I arrived on a Wednesday and never left!

What did

you find needed to be done at the winery to

improve the viniculture?

When I

arrived at Tenuta di Arceno in 2002, I had the

opportunity to work under Seillan. With

his decades of experience, Pierre conducted

detailed studies of the soil, topography and

climate to gain a complete understanding of

the land. He mapped elevation changes and

differentiation points between the estate’s

ten mesoclimates and diversity of soils. It

was according to these data points that Pierre

established new vineyard plantings and

implemented a micro-cru approach to

winemaking—parceling the estate into more than

60 single blocks with the intent to farm each

individually. In Tuscany in the early 2000s,

this approach was still very avant-garde for

the region. So, while much

of the legwork had been completed by the time

I arrived, it is also where the story begins.

We harvested the first fruit off the vines in

2002, and the approach has remained consistent

through the years in our focus on the

vineyards. In terms of the steps to improve,

this has been a process over the last two

decades of gaining a better understanding and

intimate knowledge of each block – then

listening, observing and farming according to

the nuances and personality of each.

The knowledge we bring to the wines today has

been accumulated over the last two decades of

hands-on work in the vineyards. Alongside the

vineyard manager, Michele Pezzicoli, who has

been with the winery since 1995, we have

tended the vines together for nearly 20 years

and use this experience as we approach each

new vintage.

How would

you describe the terroir vis-à-vis other

Chianti estates and California?

The estate is located in Castelnuovo

Berardenga, which is the southernmost commune

of Chianti Classico. It has a continental

climate and is comparatively warmer than other

regions within Chianti Classico, with cooler

temperatures as the hillsides rise in

elevation.

The estate comprises 1,000 total hectares

(2,500 acres) within the region, and only 10%

of the land is planted to vine (220 acres).

The expanse of the estate allowed us to be

selective in the planting process and to

choose the most optimal sites for the

vineyards. The estate has ten distinct

mesoclimates and is home to a diversity of

soils—from clay, galestro, sandstone and

basalt—with elevation ranges from 350 to 600

meters. This variability in elevation, soils

and temperatures, allows us to time the

picking dates for each block and variety as

they reach optimal ripeness. In this sense,

the diversity of our terroir is an important

contributing factor that allows us to produce

the best possible wines.

Of Chianti Classico’s nine communes, the wines

of Castelnuovo Berardenga are stylistically

distinct and often considered riper and

rounder as compared to their counterparts to

the north. A common reference locally is that

the Chianti Classico wines from Castelnuovo

Berardenga are “brunelleggianti,” a reference

to their resemblance to the great Sangiovese

wines of Brunello, or “brunelleggiare,”

in how they behave and act like Brunello

wines.

How

have the wines evolved over your time with

the winery?

Tenuta di Arceno was established with a

long-term vision to make wines that rivaled

the best in the world, and this evolution has

been 20 years in the process. When we embarked

on this journey for Tenuta di Arceno, we were

fortunate to have the resources to set

ourselves up for success in our micro-cru

approach.

Though the winemaking approach has

largely remained consistent over time, we have

changed in the process. It takes years of

trial and error to understand the details of

each block. Like people, each block has its

own personality and needs in the vineyard and

winery. By farming each block individually,

we’ve been able learn these nuances of the

terroir in extreme detail.

Our Sangiovese wines have evolved to showcase

three distinct expressions of the variety—from

Chianti Classico Annata, Riserva, and now 100%

varietal Strada al Sasso Gran Selezione. Each

preserves the bright red fruit and playful

energy of Sangiovese, while also revealing its

layers of complexity.

With our three Toscana IGT wines, the intent

has been to showcase the world-class potential

of these varieties in Tuscany, particularly

the high caliber of Cabernet Franc and Merlot.

With our flagship Arcanum and Valadorna wines,

the evolution has been a gradual progression

to 100% varietal expressions, while continuing

to refine the process that yields their

longevity in the cellar.

How do you

envision the winery and wines evolving in

the next 10 years?

One of the most exciting developments will be

the release of Arcanum 2016 and Valadorna

2018—marking the move for both wines to 100%

varietal Cabernet Franc and Merlot,

respectively. This has been a long-term vision

for the wines, and we are excited to arrive at

this moment of sharing them with the market.

We are constantly experimenting with new

sites, varieties and single vineyard

expressions. We’re hoping to plant our first

white variety at higher elevation in the

hillsides of Castelnuovo Berardenga next year,

and exploring new single vineyard expressions

from the seven “grands crus” sites on the

estate.

Finally, sustainable farming continues to be a

focus going forward. We have employed

sustainable practices at the estate since

1994, and it is increasingly important for the

long-term preservation of the land to

prioritize soil health and vitality, and we

believe it yields positive benefits in the

resulting wines.

How

has COVID-19 impacted work in the vineyards?

Nature

remains

indifferent to a global pandemic, but the

constant progression of a vine’s lifecycle was

a source of comfort and consistency. Though we

closed our tasting room, vineyard work

continued with appropriate safeguards and

precautionary measures in place under

legislation, and we feel fortunate that our

team has remained safe and in good health.

How

has it impacted sales and export?

Italy was one of the first countries to lock

down in the early part of 2020, but

fortunately we continued to maintain sales and

fulfill orders while also growing exports.

Although we miss seeing our tasting room

guests and buyers in-person, virtual channels

have allowed us to keep in touch with our

customers and created a new avenue for

engagement. As part of the Jackson Family

Wines portfolio, we have access to a broad

North American and global distribution

network, which has been an incredible asset

during the pandemic. The United States and

Canada continue to be our primary export

markets, supported by Australia, Switzerland,

the Netherlands and the United Kingdom.

The

rise in alcohol levels in red wines around

the world is nothing short of

astonishing, with 14.5% becoming a norm. How

much of this is due to global warming

and how much to winemakers

who deliberately seek to boost their

wines to higher levels?

The threat of climate

change and its impact to the wine industry is

experienced at a global level. Certainly,

there are winemakers who pursue a style, and

as part of that may seek higher alcohol

levels. But across the region, warmer weather

has moved harvest dates earlier and yielded

incremental increases in ripeness and alcohol

levels.

Fortunately, Sangiovese is a late ripening

variety and so the negative effects of climate

change are delayed. At this stage, it’s hard

to know if we’ll ever return to the days of

12.5-13% Sangiovese. In the years ahead, it is

likely for the wines to remain around 14% and

possibly to approach 15% in very hot years. In

the short-term, riper Sangiovese has not been

a negative thing for Chianti Classico, and the

last several years have produced some of the

region’s most exceptional wines. With other

varieties, we can adapt by ensuring the

correct varieties are planted in optimal

soils, and through meticulous canopy

management to create shade for grapes like

Merlot that are more sensitive to heat.

But the impacts of climate change in Chianti

Classico are not only in relation to ripeness

and shortened hang time. Like many global wine

regions around the world, Chianti Classico has

struggled with unpredictable weather patterns

and severe drought and these factors impact

yields, fruit set, ripening, and risk of rot

and disease.

What

is your feeling about wines at 14.5% and

above?

My

feeling

about wine at any percentage of alcohol is

that it must be in balance. There are many

wines above 14.5% that show a low perception

of alcohol, and equally wines below 14% that

lack balance and integration. In my opinion,

quality wines aim for harmony between the

fruit, acid, alcohol and tannin, and pursue a

sense of balance as guided by variety and

place. Throughout many years of tasting, I’ve

enjoyed wines across the spectrum of alcohol

levels, and have been so often surprised or

mistaken in my assumptions—that is one of the

great pleasures of wine—that I’ve learned to

avoid broad generalizations.

As the

non-Classico Chiantis are now better made

and becoming better known, what today are

the distinctions?

Chianti Classico is in the heart of the

Chianti region and considered the historical

birthplace for quality wine from Tuscany. The

region was one of the first delineated wine

appellations in the world and set a global

standard for quality wine production. For

many people, the Gallo Nero still symbolizes

this commitment to quality and excellence in

the glass—not to mention more than 300 years

of tradition!

There are general distinctions as it relates

to production differences for Chianti DOCG and

Chianti Classico DOCG. For example, Chianti

DOCG has a lower minimum requirement for

Sangiovese (70% compared to 80% in Chianti

Classico), permits the use of white varieties,

and allows for higher yields as compared to

Chianti Classico.

Stylistically, the wines from Chianti

Classico are marked by their acidity and often

come from vineyards planted at higher

elevation, as is the case for the wines from

Tenuta di Arceno. While Chianti can come from

across the region (excluding Chianti

Classico), the wines for Chianti Classico

remain committed to a precise geographical

zone rooted in the historic heart of the

region.

For the most, Chianti wines are still intended

for early consumption, but the debut of the

Gran Selezione category has allowed producers

from Chianti Classico to showcase complex and

age-worthy expressions of 100% varietal

Sangiovese. Like the Strada al Sasso Gran

Selezione, many of these wines are also single

vineyard expressions.

How

has the label IGT affected Tuscany?

Though global recognition for the Super Tuscan

category did not arrive until the mid-2000s,

Tuscan producers have been experimenting with

international varieties since the 1940s. The

category was created with a sense of freedom

and determination to pursue the best quality

possible—without restriction or limitation.

The producers who continue

to pursue Toscana IGT are dedicated to quality

and believe that non-traditional varieties can

produce not only worthy, but world-class

expressions of the Tuscan terroir. Today, many

of the most valuable and sought-after wines

from Tuscany, and possibly the world, are

comprised of Cabernet Franc and Merlot—wines

like Sassicaia, Le Macchiole, and Masseto.

For Tenuta di Arceno, the vision for Cabernet

Franc and Merlot began in 1994 with a detailed

understanding of the estate and the potential

for these varieties. Our progression over the

last 20 years has been about refining the

process, and culminates with the move to 100%

varietal for two of our flagship

bottlings—Arcanum (100% Cabernet Franc with

2016 vintage) and Valadorna (100% Merlot with

2018 vintage).

The recognition of the Super Tuscan category

allowed Tuscany to compete on a global stage.

But understanding the category today, and its

evolution, means recognizing its diversity.

The category allows us to express the full

capacity of the land and expand the

biodiversity of both native and non-native

varieties. And yet, within this range of

expressions, the best wines remain true to an

identity and personality that is undeniably

Tuscan.

Like most things, the Super Tuscan, or Toscana

IGT, category moved too far in one direction,

only to come back again. The category was

flooded by wines capitalizing on a trend and

favoring “style” over quality, varietal

expression, and sense of place.

Understandably, it sparked a reinvigoration

and recommitment to the region’s history,

traditions and native varieties.

But the story for Tenuta di Arceno—and I

believe for Tuscany—is not of one or the

other. Since our first days, Tenuta di Arceno

has been dedicated equally to the production

of Chianti Classico DOCG and Toscana IGT

wines, and embraced both Sangiovese and

international varieties. For

us, it is a duality that is not mutually

exclusive. It is an honest reflection of the

region, its diversity and evolution, grounded

in a relentless pursuit to make the best

possible wines from our corner of Castelnuovo

Berardenga.

❖❖❖

“Potatoes

Will

Make Their Triumphant Return to Taco Bell’s

Menu” By Rachel Sugar, New York Magazine

(1/14/21).

Sponsored by

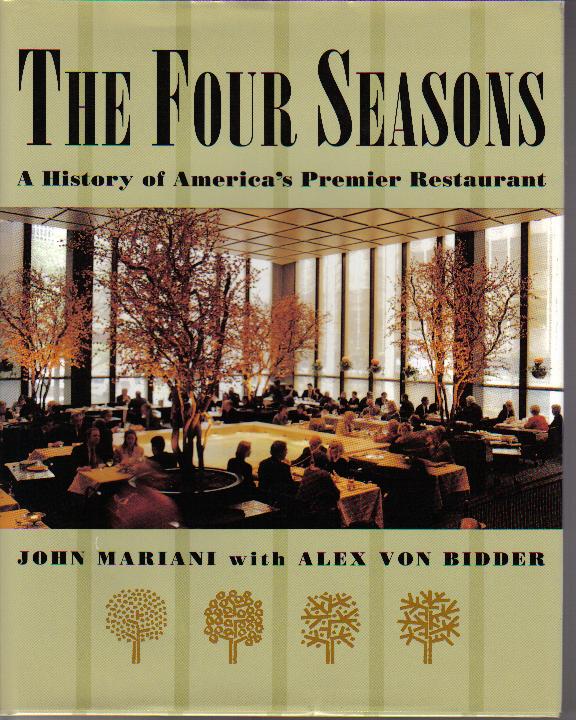

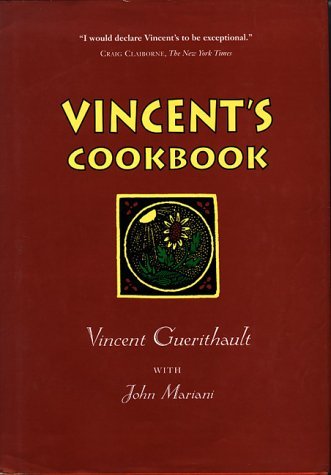

Any of John Mariani's books below may be ordered from amazon.com.

The Hound in Heaven

(21st Century Lion Books) is a novella, and

for anyone who loves dogs, Christmas, romance,

inspiration, even the supernatural, I hope you'll find

this to be a treasured favorite. The story

concerns how, after a New England teacher, his wife and

their two daughters adopt a stray puppy found in their

barn in northern Maine, their lives seem full of promise.

But when tragedy strikes, their wonderful dog Lazarus and

the spirit of Christmas are the only things that may bring

his master back from the edge of despair.

The Hound in Heaven

(21st Century Lion Books) is a novella, and

for anyone who loves dogs, Christmas, romance,

inspiration, even the supernatural, I hope you'll find

this to be a treasured favorite. The story

concerns how, after a New England teacher, his wife and

their two daughters adopt a stray puppy found in their

barn in northern Maine, their lives seem full of promise.

But when tragedy strikes, their wonderful dog Lazarus and

the spirit of Christmas are the only things that may bring

his master back from the edge of despair. WATCH THE VIDEO!

“What a huge surprise turn this story took! I was completely stunned! I truly enjoyed this book and its message.” – Actress Ali MacGraw

“He had me at Page One. The amount of heart, human insight, soul searching, and deft literary strength that John Mariani pours into this airtight novella is vertigo-inducing. Perhaps ‘wow’ would be the best comment.” – James Dalessandro, author of Bohemian Heart and 1906.

“John Mariani’s Hound in Heaven starts with a well-painted portrayal of an American family, along with the requisite dog. A surprise event flips the action of the novel and captures us for a voyage leading to a hopeful and heart-warming message. A page turning, one sitting read, it’s the perfect antidote for the winter and promotion of holiday celebration.” – Ann Pearlman, author of The Christmas Cookie Club and A Gift for my Sister.

“John Mariani’s concise, achingly beautiful novella pulls a literary rabbit out of a hat – a mash-up of the cosmic and the intimate, the tragic and the heart-warming – a Christmas tale for all ages, and all faiths. Read it to your children, read it to yourself… but read it. Early and often. Highly recommended.” – Jay Bonansinga, New York Times bestselling author of Pinkerton’s War, The Sinking of The Eastland, and The Walking Dead: The Road To Woodbury.

“Amazing things happen when you open your heart to an animal. The Hound in Heaven delivers a powerful story of healing that is forged in the spiritual relationship between a man and his best friend. The book brings a message of hope that can enrich our images of family, love, and loss.” – Dr. Barbara Royal, author of The Royal Treatment.

|

The Encyclopedia of American Food and Drink by John F. Mariani (Bloomsbury USA, $35) Modesty forbids me to praise my own new book, but let me proudly say that it is an extensive revision of the 4th edition that appeared more than a decade ago, before locavores, molecular cuisine, modernist cuisine, the Food Network and so much more, now included. Word origins have been completely updated, as have per capita consumption and production stats. Most important, for the first time since publication in the 1980s, the book includes more than 100 biographies of Americans who have changed the way we cook, eat and drink -- from Fannie Farmer and Julia Child to Robert Mondavi and Thomas Keller. "This book is amazing! It has entries for everything from `abalone' to `zwieback,' plus more than 500 recipes for classic American dishes and drinks."--Devra First, The Boston Globe. "Much needed in any kitchen library."--Bon Appetit. |

"Eating Italian will never be the same after reading John Mariani's entertaining and savory gastronomical history of the cuisine of Italy and how it won over appetites worldwide. . . . This book is such a tasteful narrative that it will literally make you hungry for Italian food and arouse your appetite for gastronomical history."--Don Oldenburg, USA Today. "Italian

restaurants--some good, some glitzy--far

outnumber their French rivals. Many of

these establishments are zestfully described

in How Italian Food Conquered the World, an

entertaining and fact-filled chronicle by

food-and-wine correspondent John F.

Mariani."--Aram Bakshian Jr., Wall Street

Journal.

"Equal parts

history, sociology, gastronomy, and just

plain fun, How Italian Food Conquered the

World tells the captivating and delicious

story of the (let's face it) everybody's

favorite cuisine with clarity, verve and

more than one surprise."--Colman Andrews,

editorial director of The Daily

Meal.com. "A fantastic and fascinating

read, covering everything from the influence

of Venice's spice trade to the impact of

Italian immigrants in America and the

evolution of alta cucina. This book will

serve as a terrific resource to anyone

interested in the real story of Italian

food."--Mary Ann Esposito, host of PBS-TV's

Ciao

Italia. "John Mariani has written the

definitive history of how Italians won their

way into our hearts, minds, and

stomachs. It's a story of pleasure over

pomp and taste over technique."--Danny Meyer,

owner of NYC restaurants Union Square

Cafe, The Modern, and Maialino.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Everett Potter's Travel Report:

Everett Potter's Travel Report:

Eating Las Vegas

JOHN CURTAS has been covering the Las Vegas

food and restaurant scene since 1995. He is

the co-author of EATING LAS VEGAS – The 50

Essential Restaurants (as well as

the author of the Eating Las Vegas web site: www.eatinglasvegas.

He can also be seen every Friday morning as

the “resident foodie” for Wake Up With the

Wagners on KSNV TV (NBC) Channel 3 in

Las Vegas.

Eating Las Vegas

JOHN CURTAS has been covering the Las Vegas

food and restaurant scene since 1995. He is

the co-author of EATING LAS VEGAS – The 50

Essential Restaurants (as well as

the author of the Eating Las Vegas web site: www.eatinglasvegas.

He can also be seen every Friday morning as

the “resident foodie” for Wake Up With the

Wagners on KSNV TV (NBC) Channel 3 in

Las Vegas.

MARIANI'S VIRTUAL GOURMET

NEWSLETTER is published weekly. Publisher: John Mariani. Editor: Walter Bagley. Contributing Writers: Christopher Mariani,

Robert Mariani, Misha Mariani, John A. Curtas, Gerry Dawes, Geoff Kalish,

and Brian Freedman. Contributing

Photographer: Galina Dargery. Technical

Advisor: Gerry

McLoughlin.

If you wish to subscribe to this

newsletter, please click here: http://www.johnmariani.com/subscribe/index.html

© copyright John Mariani 2021