Claude Monet, "Le Dejeuner sur l'Herbe avec Gustave Courbet" (1863)

IN THIS ISSUE

The Master Ham Carvers of Spain Part One

By Gerry Dawes

NEW YORK CORNER

JUNG SIK

By John Mariani

CAPONE'S GOLD

Chapter Three

By John Mariani

NOTES FROM THE WINE CELLAR

CHAMPAGNE GOES GREEN

By John Mariani

❖❖❖

Spain’s

Ibérico Knife Artists

Part

One

Text

and Photos By Gerry Dawes

The

cortadores

are professionals employed by the producers of the

high-ticket Ibérico

hams and many work for the same producer until they

retire. The pigs’ acorn

diet marbles the hams with a luxurious kind of ivory

fat that tastes of nuttiness from the acorns and

consists of mono-unsaturated oleic acid, which

actually lowers evil LDL cholesterol and boosts the levels of

the more benign HDL cholesterol. In fact, the

promoters of jamón

Ibérico de bellota are so enthusiastic about

the healthful qualities of the oleic fatty acids

that they sometimes refer to the Ibérico

pigs as “olive trees on the hoof.”

The

cortadores

are professionals employed by the producers of the

high-ticket Ibérico

hams and many work for the same producer until they

retire. The pigs’ acorn

diet marbles the hams with a luxurious kind of ivory

fat that tastes of nuttiness from the acorns and

consists of mono-unsaturated oleic acid, which

actually lowers evil LDL cholesterol and boosts the levels of

the more benign HDL cholesterol. In fact, the

promoters of jamón

Ibérico de bellota are so enthusiastic about

the healthful qualities of the oleic fatty acids

that they sometimes refer to the Ibérico

pigs as “olive trees on the hoof.”Sometimes, if there is a bumper crop of acorns, the pigs can engorge themselves to the point that this vegetable-like oil actually pools between layers of their muscles and can cause problems for the pigs. One day a few years ago during a lull when he was cutting jamones at the Pedroches stand at Barcelona’s sprawling biennial Alimentaria food fair, Pedroches Maestro Cortador Clemente Gómez pointed out a pool of oil seeping out from the muscles of a ham he was cutting and told me:

“If these pigs eat too many

acorns during la

montanera, the two to three months they are

allowed to roam free-range in the hills of

Extremadura and northern Andalucía, foraging on

grass, plants, herbs and a slew of acorns—the oleic

acid they produce from the nuts can seep out from

their muscles and make it painful for them to walk.”

“If these pigs eat too many

acorns during la

montanera, the two to three months they are

allowed to roam free-range in the hills of

Extremadura and northern Andalucía, foraging on

grass, plants, herbs and a slew of acorns—the oleic

acid they produce from the nuts can seep out from

their muscles and make it painful for them to walk.”I longed for a spoon and a small container to take away some of the oil from the ham Gómez was cutting (right). At Madrid Fusión 2018, one of the world’s top gastronomic conferences, I saw that someone had finally packaged this oil for use in kitchens, but the aceite de jamón Ibérico they were offering was actually ham fat melted in olive and/or sunflower oil and was not the real pure essence that Gómez showed me.

A fenómeno who stands apart from other ham carvers is Florencio “Flores” Sanchidrián, a 59-year old force-of-nature from the historic provincial capital of Ávila (Sanchidrián is a village north of Ávila) in the mountains northwest of Madrid. Sanchidrián is Spain’s—and the world’s—consummate Maestro Cortador. Upon watching his unique ham-cutting flourishes, one senses that within Flores Sanchidrián there is the soul of a bullfighter and/or flamenco dancer.

When he lines up to slice a

ham, Sanchidrián torques his body like a flamenco

dancer and at times profiles like a matador getting

in position for the kill. Usually he

also dons garb complete with a headband that brings

to mind a samurai maestro.

When he lines up to slice a

ham, Sanchidrián torques his body like a flamenco

dancer and at times profiles like a matador getting

in position for the kill. Usually he

also dons garb complete with a headband that brings

to mind a samurai maestro. In addition to his unique distinctive style, Sanchidrián (left) is a born storyteller who entertains as he slices, talking about what makes each particular ham special. He claims that to perfect his craft he locked himself in a convent with his knives and five hams and water.

“Iberian ham speaks of the countryside, pasture, nature and freedom,” Sanchidrián in his poetic mode says. “Acorn-fed Ibérico ham is nourished by the four elemental forces of life—earth, water, fire and wind. The earth nourishes the animal’s life, water feeds its soul, fire gives the heat for the secador (drying) process and the air (curing) exempts it from sin! Acorn-fed Ibérico hams are like wines; depending upon the year, good years come like wine vintages and, like wines, gran reserva hams are made.”

Wielding in each hand two long thin flexible slicing blades with pointed tips, Sanchidrián somehow manages to carve paper-thin slivers of ham and cajole them into a line of curls along the blade he is not using for cutting. With a deft flick of his wrist, he spins each slice around the blade, and then nudges them into the line along the other blade holding half a dozen other freshly sliced “without sin” pieces of jamón Ibérico. With the sharp pointed tip of one of the long knives, he skewers any recalcitrant, presumably sinful slices, flips them into curls and adds them to the row on the other blade. Sanchidrián does the same with the second blade until both knives have a row of curled jamón slices, artistically arranged in a single layering. In his native Ávila, at the Restaurante Rincón de Jabugo, which he owns with working partner Benjamín Rodríguez, he demonstrated this for me, letting me sample some of the slices. (He is also a partner at Restaurante El Matadero, across from Madrid’s former matadero (slaughterhouse) in the Arganzuela barrio

of Madrid.)

of Madrid.) “The first hams that come out each year have the taste of green almonds. The same ham three months later now tastes like ripe almonds,” Sanchidrián told me. “In a good year, the pig has eaten acorns and had a good diet, so the hams taste of hazelnut and wild herbs; gran reserva hams have the taste of walnuts and wild mountain herbs.”

Sanchidrián has his detractors, some of whom consider him as the cortador de jamón equivalent of Manuel Benitez “El Cordobés,” the famous tremendista, multi-millionaire “Beatle bullfighter” of the 1960s and 1970s. Jesús González (right), the Dehesa de Extremadura Cortador, mentioned no names, but says he does not like what he calls los malabaristas del jamón (ham jugglers) and said that “the star should be the ham and not the carver.” Echoing González, Joselito’s Maestro Cortador Ernesto Soriano told me, “I am a professional who thinks that a carver cannot be above the ham, which unfortunately today happens a lot, and that cannot be.” (Of course, both González and Soriano are ham carver employees of major ham producers; Sanchidrián is not.)

Carrasco Ibéricos’ official cortador, Pedro Seco, has been cutting ham for 37 years, professionally for more than 25 years, beginning “in a high-end restaurant in Madrid, where I was working as a waiter. Between periods of waiting on customers, I began cutting the hams to serve my colleagues and they told me that I did a great job of carving the ham for them, so it evolved into a profession and I was chosen to be the cortador for Carrasco Ibéricos.”

All of the Maestros Cortadores de Jamón may take several hours to whittle down a ham one slice at a time. Seco guesses he has cut 37,000 hams in his career.

Jesús González León carves hams for the D. O. P. Dehesa de Extremadura at shows and official functions. González cuts quite a figure himself in his custom-made cortador’s tunic and his sleek shaved bald dome and gray-streaked fine-line Imperial goatee. He also has a consulting business that deals in all aspects of ham procurement and ham carving. In 2018, at the Madrid Fusión gastronomic summit, he told me he is self-taught and began carving hams at Restaurante el Clavo in the out-back Extremaduran town of Valencia de Alcántara in 1988. When González began carving hams, the profession of cortador de jamones was scarcely a knife-gleam in the eyes of fledgling ham carvers. The designation cortador de jamones did not exist, let alone the lofty title of Maestro Cortador. As ham carving came to be more appreciated it became an event at trade shows like the Salón de Gourmets in Madrid. In 1998, Jesús González began entering ham cutting contests and won five of them. (The first jamón Ibérico Denominación de Origen Protegida, Guijuelo, was not recognized until 1986 and la Dehesa de Extremadura, which is in González’s home region, did not attain D. O. P. status until 1990.)

For the Dehesa de Extremadura D. O. P., González estimates he carves 500 to 600 hams per year. When asked whether he ever got codo de tenista, (tennis elbow) from cutting hams, he said, “No, ham carvers get tendonitis of the shoulder, not the elbow.”

►

This article is excerpted

from

Gerry Dawes’s upcoming book, Sunset in a

Glass: Adventures of a Food and Wine Road

Warrior in Spain.

❖❖❖

JUNG SIK

2 Harrison Street (at Franklin Street)

212-219-0900

By John Mariani

Photos by Dan Ahn

Somehow I missed eating at Jung Sik when it opened in 2012 without much fanfare, and then, as time went on, I never got around to it, despite its receiving two Michelin stars. Now that I have, I could kick myself for not getting to Jung Sik sooner, because the cuisine of owner Jung Sik Yim, whose first restaurant, Jung Sik Dang, debuted in Seoul in 2009, is among the most refined and sensibly creative in New York right now. Not for him are modernist fantasies or molecular lab experiments. His food is beautifully crafted but, overall, possesses flavor combinations that one has never thought of, much less thought would work. And they really do.

Yim’s opening in

Seoul was, from all reports, a shot across the bow,

bringing an entirely new style of cooking to South

Korea, though it would be difficult to puzzle out

what makes much of it Korean. His sensibilities are

not like the overelaborated razzle-dazzle intentions

of David Chang. Yim is more interested in a

minimalism that is actually complex, whereby to look

at his dishes is not to know how much thought went

into them. Sometimes all that work still comes out

as a rather bland reality, but in most the results

can be wondrous.

Yim’s opening in

Seoul was, from all reports, a shot across the bow,

bringing an entirely new style of cooking to South

Korea, though it would be difficult to puzzle out

what makes much of it Korean. His sensibilities are

not like the overelaborated razzle-dazzle intentions

of David Chang. Yim is more interested in a

minimalism that is actually complex, whereby to look

at his dishes is not to know how much thought went

into them. Sometimes all that work still comes out

as a rather bland reality, but in most the results

can be wondrous.The TriBeCa premises used to be the warm-hearted Chanterelle festooned with sprays of flowers. Now, Jung Sik is basically one long room with a picture window, a slatted polished wood wall, and exceptionally comfortable cream-colored banquettes and booths set with double tablecloths and first-rate stemware for each kind of wine. Lighting is amiable and allows you to see the beauty on the plates; the eclectic mix of music is played nice and low. When we dined there, when New York restaurants were allowed 50% capacity, only four tables were taken (along with a few claustrophobic-looking huts outside), so the noise level was very pleasant, but even with more tables, I can’t imagine it really being much louder.

There are two menus offered at Jung Sik. The five-course menu is $165, with an optional wine pairing for $110,

and the seven-course menu is

$200, with an optional wine pairing for $140, making

this one of the most expensive restaurants in the

city. And be aware that, if you are a table of two

or four, everyone must take one or the other option,

meaning you can’t order seven courses and your

friend five, because it would “interrupt the flow.”

and the seven-course menu is

$200, with an optional wine pairing for $140, making

this one of the most expensive restaurants in the

city. And be aware that, if you are a table of two

or four, everyone must take one or the other option,

meaning you can’t order seven courses and your

friend five, because it would “interrupt the flow.”

Yim apparently is biding his time back in Seoul, and the night I visited the executive chef was off and the sous-chef who cooked that night “left early.” The heralded pastry chef left the restaurant three weeks earlier. This was all a bit off-putting, but nevertheless the kitchen staff (all women) seems well trained to deliver exquisite cuisine, as is the wait staff, whose every member knows every detail about every dish.

Apparently they once served bread at Jung Sik but no longer, so you will be ravenous by the time the lovely little charabanc (amuses) arrive, set on individual ceramic stools, including a paper crisp tuile of tuna loin with cucumber, chive and sesame aïoli; a steamed egg finished with a gamte (seaweed) and shellfish foam; wagyu beef tartare seasoned with truffle cream, served on toasted brioche, with Parmesan and black pepper; velvety foie gras mousse in a Berber brik tartlet, with apple jam garnished with toasted shaved hazelnut; and “compressed” Chilean peach topped with lime zest, sour cream, bacon chip and candied pecans that would have been better as a dessert.

Then

came the various savory and sweet courses, beginning

with luscious bluefin tuna belly layered with

slow-cooked egg yolk and insipid Bulgarian sturgeon

roe, which had a nice textural contrast of crispy

quinoa. Next up was a lightly grilled langoustine

served with smoky sabayon and hyssop oil, making for

delectably complementary flavors. One of the

signature dishes for good reason at Jung Sik is the

octopus braised for an hour in dashima

kelp broth, then fast-seared till crisp, served over

gochujang

(chili paste) aïoli and finished with fine herbs.

Then

came the various savory and sweet courses, beginning

with luscious bluefin tuna belly layered with

slow-cooked egg yolk and insipid Bulgarian sturgeon

roe, which had a nice textural contrast of crispy

quinoa. Next up was a lightly grilled langoustine

served with smoky sabayon and hyssop oil, making for

delectably complementary flavors. One of the

signature dishes for good reason at Jung Sik is the

octopus braised for an hour in dashima

kelp broth, then fast-seared till crisp, served over

gochujang

(chili paste) aïoli and finished with fine herbs. Mandoo are Korean dumplings, here stuffed with foie gras and kimchi, topped with a sheer sheet of wagyu and swimming in a beef broth (left) known as gom-tang—a good dish, but the broth, by any name, was dreary, despite its three-day preparation time. An elaborate dish that paid off was myeong ran (cod roe) atop seaweed rice and pearl barley, finished with more seaweed, slow-cooked egg yolk and crispy quinoa, delicious if a bit too similar to the tuna tuile.

Alaskan black cod is a marvelous fish, often cloyed with sweet sauces, but here its essential flavor is unmasked, served in a delicate clam stock foam. Branzino is first steamed, then charcoal-grilled and served over a bed of white kimchi, with a vial of sesame oil. (These tiny vials are a leitmotif at Jung Sik.) Kimbap sushi is stuffed with woodsy truffled rice, bluefin tuna belly, and kimchi, finished with a tangy mustard sauce (right).

Next come the meat dishes. You won’t find a cook-it-yourself brazier at Jung Sik, and the traditional galbi marinated shortribs of beef are wagyu here, lightly grilled and served over a bed of seasoned mushroom rice with kakdugi radish kimchi and sesame leaf. Superb Iberico Pluma de Bellota pork came with white asparagus—too early in the season to be very sweet—a sunchoke puree, micro mizuna and mustard salad with calamansi vinaigrette, crosne, and kalchi (beltfish) jus.

This

was a lot of courses, but my wife and I were still

ready for some delicate desserts. “NY Seoul” was

choux pastry filled with brown rice cream and pecan

praline, caramel, corn dough and vanilla ice cream.

A signature “trick of the eye” dessert was a very

soft, almost pudding-like baby banana, with a

cannoli made from a white chocolate shell filled

with dulcey cream, banana cremeux. A

Bailey’s banana cake was accompanied by coffee ice

cream and chocolate hazelnut crumble. Strawberries,

both cultivated and wild, are topped with an aloe

sorbet served on a corn sable cookie and finished

with black pepper and strawberry juice. Of

course, there are delightful petit-fours and rich

buttery chocolates. It‘s a tour de force at the end

of such a splendid meal.

This

was a lot of courses, but my wife and I were still

ready for some delicate desserts. “NY Seoul” was

choux pastry filled with brown rice cream and pecan

praline, caramel, corn dough and vanilla ice cream.

A signature “trick of the eye” dessert was a very

soft, almost pudding-like baby banana, with a

cannoli made from a white chocolate shell filled

with dulcey cream, banana cremeux. A

Bailey’s banana cake was accompanied by coffee ice

cream and chocolate hazelnut crumble. Strawberries,

both cultivated and wild, are topped with an aloe

sorbet served on a corn sable cookie and finished

with black pepper and strawberry juice. Of

course, there are delightful petit-fours and rich

buttery chocolates. It‘s a tour de force at the end

of such a splendid meal.Jung Sik’s has a trophy wine list that may well be

of interest to

Korean billionaires who think nothing of dropping

$14,000 for a Romanée-Conti, but for the rest of us

there is precious little under $150 that is

appealing, which may be why the other tables that

night seemed to be nursing a wine by the glass or

none at all. The cheapest wine by the glass is a

dessert wine for $24, the most expensive, an Opus

One 2016, is $90. Curiously enough, the best buys on

the list are the magnums, like Bois de Boursan

“Tradition” for $200.

of interest to

Korean billionaires who think nothing of dropping

$14,000 for a Romanée-Conti, but for the rest of us

there is precious little under $150 that is

appealing, which may be why the other tables that

night seemed to be nursing a wine by the glass or

none at all. The cheapest wine by the glass is a

dessert wine for $24, the most expensive, an Opus

One 2016, is $90. Curiously enough, the best buys on

the list are the magnums, like Bois de Boursan

“Tradition” for $200.The prices at Jung Sik are arguably justified by the superior cuisine, though some of the ingredients from such far-flung sources, like wagyu, might not be all that necessary when used only in such minuscule amounts. You will have a serene evening at Jung Sik, and as long as you know what you’re paying for it, it will be uniquely wonderful.

CAPONE’S

GOLD

Katie

Cavuto and David Greco agreed to

start work immediately on the Capone

project, so she booked a room at a

local motel and was at his door the

next morning by nine, to find him

yet again out in the yard killing

hogweed.

“I know, I know, don’t shake

hands,” she said.

“Hey. You look chipper this

morning,” he said, immediately

regretting his choice of words. “Had

breakfast?”

“I just grabbed a cup of coffee

in the motel lobby.”

David

shook his head and said, “You can’t go

all day on that. I

haven’t eaten yet either. I’ll

make us breakfast.”

They entered his

house, a split-level ranch that appeared

to have been emptied by its last

residents without taking much of the

well-worn furniture: sofa, two arm

chairs, coffee table, TV in front of the

fireplace. But it smelled clean, no

animal aromas. So

did the kitchen, which was of a good

size, with a table and a counter, with

an old professional stove and stainless

steel canopy.

David

shook his head and said, “You can’t go

all day on that. I

haven’t eaten yet either. I’ll

make us breakfast.”

They entered his

house, a split-level ranch that appeared

to have been emptied by its last

residents without taking much of the

well-worn furniture: sofa, two arm

chairs, coffee table, TV in front of the

fireplace. But it smelled clean, no

animal aromas. So

did the kitchen, which was of a good

size, with a table and a counter, with

an old professional stove and stainless

steel canopy.

David

went to wash up and returned in a fresh

tennis shirt and shorts. Looked

like he also put a comb through his

hair.

Katie was in jeans and a t-shirt,

carrying a bag of note pads and books.

“Eggs, okay with you? I’m known

for my scrambled eggs.”

“Gee, being a detective, I would

have thought you make them hard-boiled.”

David pinched his paunch and

said, “I’m more soft-boiled, but I break

eggs really well. And the eggs are

fantastic. I get them from a farm about

a mile away. They

are very happy chickens. You’ll taste

it.”

He began by chopping some onions

fine and sautéing them in butter till

they started turning golden brown. Then

he cracked four eggs into a saucepan—not

a skillet—whisking them with salt and

pepper, then put them over low heat with

some butter, a big spoonful of ricotta,

and then grated pecorino. Stirring

constantly to meld the ingredients, he

added the cooked onions just as the eggs

began to come together.

David had already heated two

plates and dropped two slices of Italian

bread into the toaster. “Can you get

some knives and forks out of that third

drawer on the left? That one, yeah. Okay

if we sit at the counter?”

Katie shrugged and placed the

cutlery on the counter just as the toast

popped up.

David portioned out the eggs onto

the warm plates.

“Let me know what you think,” he

said.

Katie tasted the eggs, which were

a brilliant yellow and very moist,

closed her eyes and said, “My God, they

are really

delicious. They’re so creamy and light!”

“Never make eggs in a skillet.

They cook too fast and get hard. You

want espresso or cappuccino?”

“Cappuccino, if it’s not too much

trouble.”

“Not at all,” he said and put a

cup under the espresso machine, then

steamed the milk. “I

apologize. I don’t make those little

heart shapes in the foam.” Then

he made himself a double espresso.

Two

eggs each don’t take long to finish, so

David wiped his mouth, made himself

another espresso and said, “So, let’s

get to work.”

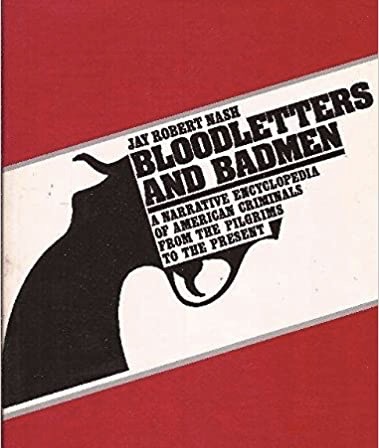

Katie seated herself across from

David and started unpacking her bag: one

legal pad, two reporter’s notebooks, a

thick manila folder, two biographies of

Al Capone and a copy of Jay Robert

Nash’s 1973 book, Bloodletters

and Badmen: A Narrative Encyclopedia

of American Criminals from the

Pilgrims to the Present.

“The Nash book is very

comprehensive but has a lot of errors,”

said David. “He tried to cover everyone

from Billy the Kid to Sam Giancana.”

“Have

you read either of these Capone bios?”

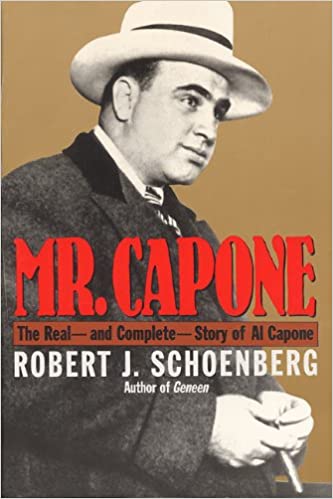

asked Katie, pulling them from the pile.

“I read the Schoenberg book when

it came out a few years ago,” said

David, picking up the author’s 1993 bio,

Mr.

Capone: The Real—and Complete—Story of

Al Capone. “Top-notch

researcher. He

spoke to a lot of Chicago and Miami cops

who were around when Capone was

operating. Of course, if we find

Capone’s gold, he’ll have to add a

chapter.”

“And then he’ll have to credit my

article and your assistance.”

“And interview us.”

David

had started to assess the brown-eyed

journalist at his kitchen counter. Good

looking woman, about thirty, a

difference of, say, fifteen to twenty

years between them. Nice

chest, Italian-American hips. Slightly

olive skin tone. Hair in a ponytail,

nails not too long, no polish. No face

makeup except for a slight blush of

lipstick and eyeliner. No designer

jeans, simple white t-shirt, probably

GAP. Flats, not sneakers. Two silver

rings, no wedding ring, small round

silver earrings. The

nose was strong, pretty little bump on

the bridge. He

had to admit, her eyes were sexy.

David

had started to assess the brown-eyed

journalist at his kitchen counter. Good

looking woman, about thirty, a

difference of, say, fifteen to twenty

years between them. Nice

chest, Italian-American hips. Slightly

olive skin tone. Hair in a ponytail,

nails not too long, no polish. No face

makeup except for a slight blush of

lipstick and eyeliner. No designer

jeans, simple white t-shirt, probably

GAP. Flats, not sneakers. Two silver

rings, no wedding ring, small round

silver earrings. The

nose was strong, pretty little bump on

the bridge. He

had to admit, her eyes were sexy.

At the same time, Katie was

sizing up the detective, thinking he fit

the mold pretty well of what she’d

thought he’d be like from his official

photo she’d seen in the newspaper. Stocky,

five-ten, strong eyebrows on a large

forehead.

The haircut was a cop’s cut,

clean at the neck and around the ears,

starting to get a little sparse at the

top. His tennis shirt revealed quite

muscular arms but not overdeveloped the

way the younger cops went for.

Katie had never really been a

crime reporter, though in her early

years

she’d cover whatever the

assignment desk editor at Bronx

News gave her, and

that

included spending days in criminal

courtrooms trying to get a story out of

the arrest of a local drug dealer or car

thief.

Later on, when she went

freelance, she wrote for some of the

city magazines, then broke into national

ones like McClure’s,

which was named after a quite famous

muckraking magazine of the 1920s that

had published authors like Willa Cather,

Jack London, Mark Twain, and Lincoln

Steffens.

The original McClure’s

went out of business in 1929, but a

wealthy New York publisher with a

passion for solid investigative

reporting titillating enough to sell to

a large audience started up the new McClure’s

in 1990 in homage to the mission of the

first.

Hence, the Capone story, which,

if it panned out, would make banner

headlines and garner TV coverage.

Katie Cavuto

had certainly proven herself a dogged

reporter on many stories. She’d

had some nominations and won some prizes

along the way for stories like her

exposé of a congressman with financial

ties to a corrupt HMO in Florida. She

also got the last interview with a major

British movie star before he died of

alcoholism.

David had never heard of Katie

Cavuto and was still waiting to hear

what new research she had before going

further with the Capone project. As

the lead detective in New York

investigating mob activities, he knew

enough history of organized crime and

had enough files of his own on modern

day gangsters that he wondered how this

nice Italian-American girl with the dark

eyes and great hips could have come up

with something novel about Capone.

Then

again, David had never spent much time

delving into Capone’s dealings—the

mobster had died three years before

David was born—except how his associates

took over the rackets upon his demise. Those

were the tentacles that still needed to

be regularly lopped off.

Being Italian-American himself,

David Greco hated the way gangsters with

names like Capone, Genovese, Bonano, and

Gallo had so indelibly tainted his

ancestors’ and contemporaries’

reputation, so that early on when he

joined the police force, he swore that

his mission would be to cripple the

Italian-led mobs and put the top bosses

away.

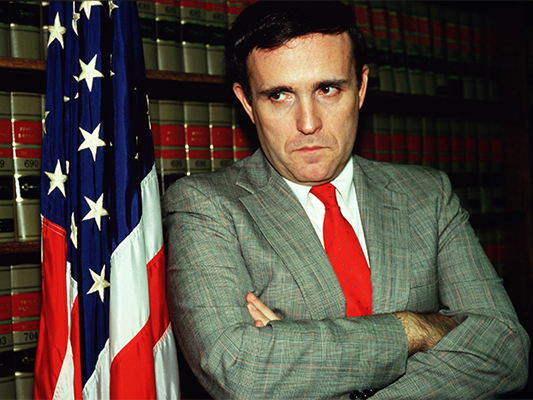

His

zeal for the job, which got him his

detective’s badge and many citations,

also brought him to the attention of

Italian-American Rudy Giuliani, first

when he was U.S. Attorney for the

Southern District of New York, then as

Mayor of New York. As

a prosecutor Giuliani always sought out

high profile cases like Wall Street

crooks Ivan Boesky and Michael Milken

along with drug lords and the heads of

organized crime. Giuliani loved the

spotlight.

His

zeal for the job, which got him his

detective’s badge and many citations,

also brought him to the attention of

Italian-American Rudy Giuliani, first

when he was U.S. Attorney for the

Southern District of New York, then as

Mayor of New York. As

a prosecutor Giuliani always sought out

high profile cases like Wall Street

crooks Ivan Boesky and Michael Milken

along with drug lords and the heads of

organized crime. Giuliani loved the

spotlight.

Longtime New York City D.A.

Robert M. Morgenthau competed for

publicity with Giuliani, who’d invented

the “perp walk”—the parading of

handcuffed “perpetrators” past

well-placed TV cameras. Also publicity

hungry were the Police Commissioners,

first Ray Kelly, then Bill Bratton,

whose job it was to face the press on a

daily basis. David Greco was more than

content to be on the streets getting the

dirty work done on their behalf. When

he saw he could rise no higher, and

after falling out with Giuliani, David

Greco retired after 20 years on the

force.

David had won all their respect,

as he did from his closest cop friends,

though, as ever, he was too often

frustrated by higher ups shutting down investigations

and

sting operations without any official

reason given.

Perhaps more importantly, David Greco

had won respect for his professionalism

from the very people he was arresting. The

mobsters felt he played fair, and, while

it was far from the case with other

cops, Greco could not be bought. If he

were ever present at one of those perp

walks, he never gloated in front of

those he had arrested. Sometimes he’d

even get a wink from the perp.

Of course, the

age-old understanding between the police

and the mob still

persisted:

The latter never ordered a hit on the

former, lest the full, concentrated

wrath of the NYPD would crash down on

them, resulting in the immediate and

wholesale arrest of scores of mobsters,

high and low, thereby decimating and

upending their secret criminal

enterprises. Indeed, David Greco and his

colleagues always thought it was a

bullshit part of The

Godfather when young Mafioso

Michael Corleone murdered the corrupt

police captain over a plate of

spaghetti.

Other than that, though, he loved

the movie.

❖❖❖

CHAMPAGNE GOES GREEN

By John Mariani

Photos courtesy of Comité Champagne.

Champagne is also working to invent new grape varieties by breeding hybrids, thereby creating varieties with effective and sustainable resistance, improving the vines’ growing capability and the quality of the wine produced in the face of a changing climate. To find out the details I interviewed Arnaud Descotes (below), director of the viticulture and environment department at the Comité Champagne.

Compared to the 30-year

baseline average from 1961-1990, the average

temperature in Champagne has risen by 1.3°C over the

past 30 years, while average rainfall has remained

steady at 700mm/year. Damage caused by spring frosts

has slightly increased due to earlier bud bursts,

despite a drop in the number of frosty nights.

Harvest in Champagne also starts 18 days earlier

than it did 30 years ago. In 2020, the region

recorded its earliest harvest start date in history,

and it was the sixth to start in August over the

past 15 years.

Is harvesting

earlier a detriment to the traditional taste of

the Champagnes?

These effects of local

warming have actually been beneficial for the

quality of grape musts produced in the region. The

beneficial effects are likely to continue if global

warming is limited to a 2°C rise. However, the

Champagne region is now exploring ideas that would

enable the inherent characteristics of its wines to

be preserved in less optimistic climate change

scenarios.

Has warming affected

the microbes in the soil that have been there for

millions of years?

No, at this stage we have

not noticed any changes.

What are some of the

other specific ways the goal will be reached?

Champagne was the first

wine-growing region in the world to equip itself

with an ambitious plan to cut carbon emissions.

Reducing bottle weight, recycling waste products,

and converting biomass are among the most

significant initiatives. The region is also focusing

on supplies and is seeking to replace fossil

fuel-based supplies with bio-sourced supplies from

agricultural resources produced in the region. From

2003-2020, the region successfully decreased the

carbon footprint of every bottle by 20 percent, cut

its use of herbicides in half, treated and recycled

100 percent of its wine effluents and 90 percent of

its industrial waste. The goal is to achieve a 75

percent decrease by 2050.

Champagne sales were

down last year by 20%. What was this due to?

Lighter

glass bottles help reduce Champagne's carbon

footprint.

We do not have information

about Champagne sales within the United States.

However, the closure of primary consumption and

sales hubs, along with the cancellation of many

events, put the business under pressure and led to

an 18.8 percent year-over-year

decline in Champagne shipments to the United States

in 2020. Globally, Champagne shipped 17.9 percent

fewer bottles in 2020 compared to the previous year,

lower than the 30 percent anticipated loss that was

initially expected.

Mating disruption of insects

reduces the need for insecticides.

During Covid and with restaurants closed, are

restaurateurs still stocking Champagnes when they

still have so much in inventory?

In 2020 we saw that many

importers and other wine professionals reduced their

stock to lower their storage costs and/or improve

their cash flow. That led to a decrease in shipments

for 2020. However, we have received information from

U.S. importers that Champagne consumption has been

higher than what shipments show. Even with this 18.8

percent loss, the United States market represented

15.8 percent of all Champagne shipments in 2020. It

remained the second highest export market in terms

of volume, only surpassed by the United Kingdom.

❖❖❖

Sponsored by

Any of John Mariani's books below may be ordered from amazon.com.

The Hound in Heaven

(21st Century Lion Books) is a novella, and

for anyone who loves dogs, Christmas, romance,

inspiration, even the supernatural, I hope you'll find

this to be a treasured favorite. The story

concerns how, after a New England teacher, his wife and

their two daughters adopt a stray puppy found in their

barn in northern Maine, their lives seem full of promise.

But when tragedy strikes, their wonderful dog Lazarus and

the spirit of Christmas are the only things that may bring

his master back from the edge of despair.

The Hound in Heaven

(21st Century Lion Books) is a novella, and

for anyone who loves dogs, Christmas, romance,

inspiration, even the supernatural, I hope you'll find

this to be a treasured favorite. The story

concerns how, after a New England teacher, his wife and

their two daughters adopt a stray puppy found in their

barn in northern Maine, their lives seem full of promise.

But when tragedy strikes, their wonderful dog Lazarus and

the spirit of Christmas are the only things that may bring

his master back from the edge of despair. WATCH THE VIDEO!

“What a huge surprise turn this story took! I was completely stunned! I truly enjoyed this book and its message.” – Actress Ali MacGraw

“He had me at Page One. The amount of heart, human insight, soul searching, and deft literary strength that John Mariani pours into this airtight novella is vertigo-inducing. Perhaps ‘wow’ would be the best comment.” – James Dalessandro, author of Bohemian Heart and 1906.

“John Mariani’s Hound in Heaven starts with a well-painted portrayal of an American family, along with the requisite dog. A surprise event flips the action of the novel and captures us for a voyage leading to a hopeful and heart-warming message. A page turning, one sitting read, it’s the perfect antidote for the winter and promotion of holiday celebration.” – Ann Pearlman, author of The Christmas Cookie Club and A Gift for my Sister.

“John Mariani’s concise, achingly beautiful novella pulls a literary rabbit out of a hat – a mash-up of the cosmic and the intimate, the tragic and the heart-warming – a Christmas tale for all ages, and all faiths. Read it to your children, read it to yourself… but read it. Early and often. Highly recommended.” – Jay Bonansinga, New York Times bestselling author of Pinkerton’s War, The Sinking of The Eastland, and The Walking Dead: The Road To Woodbury.

“Amazing things happen when you open your heart to an animal. The Hound in Heaven delivers a powerful story of healing that is forged in the spiritual relationship between a man and his best friend. The book brings a message of hope that can enrich our images of family, love, and loss.” – Dr. Barbara Royal, author of The Royal Treatment.

|

The Encyclopedia of American Food and Drink by John F. Mariani (Bloomsbury USA, $35) Modesty forbids me to praise my own new book, but let me proudly say that it is an extensive revision of the 4th edition that appeared more than a decade ago, before locavores, molecular cuisine, modernist cuisine, the Food Network and so much more, now included. Word origins have been completely updated, as have per capita consumption and production stats. Most important, for the first time since publication in the 1980s, the book includes more than 100 biographies of Americans who have changed the way we cook, eat and drink -- from Fannie Farmer and Julia Child to Robert Mondavi and Thomas Keller. "This book is amazing! It has entries for everything from `abalone' to `zwieback,' plus more than 500 recipes for classic American dishes and drinks."--Devra First, The Boston Globe. "Much needed in any kitchen library."--Bon Appetit. |

"Eating Italian will never be the same after reading John Mariani's entertaining and savory gastronomical history of the cuisine of Italy and how it won over appetites worldwide. . . . This book is such a tasteful narrative that it will literally make you hungry for Italian food and arouse your appetite for gastronomical history."--Don Oldenburg, USA Today. "Italian

restaurants--some good, some glitzy--far

outnumber their French rivals. Many of

these establishments are zestfully described

in How Italian Food Conquered the World, an

entertaining and fact-filled chronicle by

food-and-wine correspondent John F.

Mariani."--Aram Bakshian Jr., Wall Street

Journal.

"Equal parts

history, sociology, gastronomy, and just

plain fun, How Italian Food Conquered the

World tells the captivating and delicious

story of the (let's face it) everybody's

favorite cuisine with clarity, verve and

more than one surprise."--Colman Andrews,

editorial director of The Daily

Meal.com. "A fantastic and fascinating

read, covering everything from the influence

of Venice's spice trade to the impact of

Italian immigrants in America and the

evolution of alta cucina. This book will

serve as a terrific resource to anyone

interested in the real story of Italian

food."--Mary Ann Esposito, host of PBS-TV's

Ciao

Italia. "John Mariani has written the

definitive history of how Italians won their

way into our hearts, minds, and

stomachs. It's a story of pleasure over

pomp and taste over technique."--Danny Meyer,

owner of NYC restaurants Union Square

Cafe, The Modern, and Maialino.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Everett Potter's Travel Report:

Everett Potter's Travel Report:

Eating Las

Vegas JOHN CURTAS has been covering

the Las Vegas food and restaurant scene

since 1995. He is the co-author of EATING LAS

VEGAS – The 50 Essential Restaurants (as

well as the author of the Eating Las

Vegas web site: www.eatinglasvegas.

He can also be seen every Friday morning as

the “resident foodie” for Wake Up With the

Wagners on KSNV TV (NBC) Channel 3 in

Las Vegas.

Eating Las

Vegas JOHN CURTAS has been covering

the Las Vegas food and restaurant scene

since 1995. He is the co-author of EATING LAS

VEGAS – The 50 Essential Restaurants (as

well as the author of the Eating Las

Vegas web site: www.eatinglasvegas.

He can also be seen every Friday morning as

the “resident foodie” for Wake Up With the

Wagners on KSNV TV (NBC) Channel 3 in

Las Vegas.

MARIANI'S VIRTUAL GOURMET

NEWSLETTER is published weekly. Publisher: John Mariani. Editor: Walter Bagley. Contributing Writers: Christopher Mariani,

Robert Mariani, Misha Mariani, John A. Curtas, Gerry Dawes, Geoff Kalish,

and Brian Freedman. Contributing

Photographer: Galina Dargery. Technical

Advisor: Gerry

McLoughlin.

If you wish to subscribe to this

newsletter, please click here: http://www.johnmariani.com/subscribe/index.html

© copyright John Mariani 2021